With guards in short supply, Mississippi prison put gangs in charge with deadly results

Published 5:15 am Wednesday, June 26, 2019

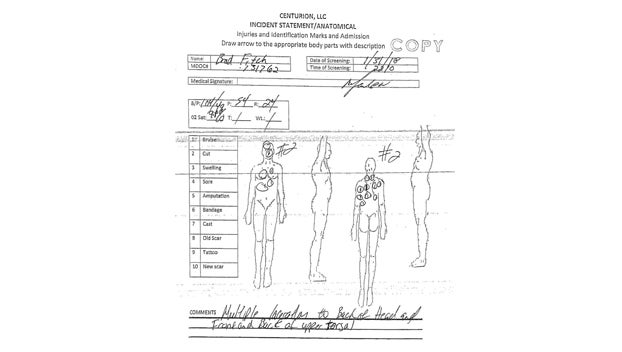

It was a prison brimming with violence, awash in weapons — and severely short on guards to patrol its cell blocks. But security-camera footage caught the action when Brad Fitch arrived in unit F at Mississippi’s Wilkinson County Correctional Facility on Jan. 31, 2018.

The two sets of sneakers, pacing outside the cell he had occupied for six hours. His race through the dayroom, his white T-shirt soaked in blood. His desperate run for the locked exit, chased by two prisoners. The slash of a handmade knife — a shank — as he stumbled.

The rain of blows that left him curled up on the floor of a shower stall in a pool of his own blood, 10 stab wounds in his back.

His attackers, after performing what investigators later concluded was a gang-ordered hit, walked calmly away. Even when a handful of guards turned up and found Fitch’s wounded body, inmates continued to mill around, heating up snacks in a microwave just yards from where he lay.

Such a nonchalant display of gang power wasn’t unusual at Wilkinson, a 950-bed maximum security prison where there have been at least four gang-related homicides in the last two years.

In fact, the warden relied on gangs to keep the peace.

Like most prisons in Mississippi and a growing number across the country, Wilkinson had trouble finding people willing to take dangerous, low-paying guard jobs (more than a third were vacant and annual turnover was close to 90 percent).

Jody Bradley, the warden, had turned to gang leaders to keep the inmates under control. His explanation of this situation is contained in a confidential “critical self-analysis” on the prison that was obtained by The Marshall Project. The internal audit was produced last December for Management & Training Corp., or MTC, the private company Mississippi pays to manage Wilkinson. The prison is located in the tiny town of Woodville near the Louisiana border.

MTC hired an outside consultant to identify risks to running the prison “in a safe and secure manner, to identify best practices and innovations, and to provide technical assistance, guidance and training,” according to the audit. The company says it does comprehensive audits every two years.

Since the report, the company has hired a new warden and says it has made other improvements, including increasing pay for guards. It recently advertised a correctional-officer job at Wilkinson paying $11.25 an hour; the minimum wage in Mississippi is $7.25 an hour.

Gang leaders asked ‘to control their men’

Wilkinson is challenging to run, according to Sara Revell, a regional vice-president at MTC. Seven hundred of the more than 900 inmates are in maximum security; 80 percent are affiliated with gangs.

To say gangs “are in charge of, running or are in control of Wilkinson County Correctional Facility, I don’t believe is accurate at all,” Revell said in an interview. “Good things are happening at Wilkinson and will continue to improve.”

Bradley, the former warden, declined to comment.

With unemployment low, prisons across the country are struggling to hire and retain guards; these jobs, despite being high risk, often pay less than that of an hourly retail worker. Staffing shortages have been blamed for violent incidents in state prisons across the country, and without enough guards, prison systems often lock down inmates, restricting them to their cells for weeks or even months.

Bradley’s response to this problem, according to the audit: “he speaks with the gang lords/leaders and asks them to ‘control their men.’ If they do not control the individuals on the unit, the Warden will place the unit on lockdown,” which means prisoners are confined to their cells with no visits, no recreation, no meals in the cafeteria.

Using gangs this way is just how Mississippi prisons operate, the warden said: “It ain’t right, but it’s the truth.” He told auditors that the head of the criminal investigations division at the Mississippi Department of Corrections, who was not named, had encouraged him to partner with gang leaders.

The corrections department “vehemently denies” that it endorses gang rule at the prison, according to a statement from its public information officer, Grace Fisher. “Under no circumstances would the MDOC convey that it condones or encourages the use of gangs to manage inmate behavior.” The agency declined requests for interviews, including with the head of the criminal investigators, Sean Smith. He could not be reached for comment.

The department says it is aware of the audit and is confident MTC is addressing the problems. Internal audits are not submitted to the state, but corrections officials can request to see copies.

Gang leaders had ‘the real control,’ audit says

Officially, Mississippi has long had a zero tolerance program for dealing with gangs such as the Vice Lords and the Gangster Disciples.

But Wilkinson’s gang leaders got special privileges. They determined who got jobs and other perks, auditors found; they were escorted by their own security details as they moved around the 950-bed prison. They decorated their cells with gang paraphernalia. They were “the ones with the real control,” according to the audit, which concluded that their power endangered both the inmates and the staff.

Dealing with gang violence can be daunting, but there’s broad consensus in the corrections profession about the dangers of giving gangs operational control. “The state should impose order,” said David Pyrooz, a sociologist at the University of Colorado Boulder who studies gangs.

He also said the number of gang-related homicides at Wilkinson was high. A 2016 survey of 39 correctional systems he did found just two gang-related killings per 100,000 inmates. Wilkinson has recently had two a year with fewer than 1,000 inmates.

Homicides in general are relatively rare in state prisons; according to federal data, there were about 70 across the country in 2015, accounting for about 2 percent of inmate deaths.

The 83-page Wilkinson audit opens a rare view into a prison run by Utah-based MTC, which operates about two dozen penal institutions, mostly in Southern states.

On pages topped by the logo of MTC Corrections, auditors describe the conditions that have made Mississippi prisons notorious: crumbling buildings where water oozed down moldy walls and drenched inmates’ beds; high levels of violence, including dozens of injuries to guards from inmate attacks; some prisoners living without soap, blankets, jackets or even food.

There were so few guards that some officers worked 95 hours of overtime in just two weeks, the audit says. Even so, they didn’t enforce basic rules, often failed to perform drug tests, and didn’t have an organized SWAT team for emergencies. They also weren’t patrolling some housing areas (they didn’t notice one prisoner was living in the wrong cell for a week — until his cellmate strangled him, the night before Fitch was attacked, according to investigative records).

Three-quarters of the guards were women (Mississippi has historically had the highest rate of female correctional officers in the country). There were not enough male guards to perform strip searches when high-risk prisoners needed to be moved.

But what really troubled the auditors was the level of gang activity at the prison — and the employees’ tolerance of it. “It never felt like staff were in control of the offender population,” according to the audit.

The audit was led by D. Scott Dodrill, a long-time employee of the Federal Bureau of Prisons who now works as a consultant. He did not respond to requests for comment.

‘I’ve seen machetes. I’ve seen daggers’

Private corrections companies try to ensure their profits by squeezing payroll, their biggest expense, said Jody Owens, a lawyer for the Southern Poverty Law Center who has led two class action lawsuits against MTC over conditions in Mississippi prisons. One of these cases is before a federal judge; in the other, the prison closed.

The companies use gangs as unpaid labor, he said. “It’s like a hospital saying we can’t perform the surgery, but we’ll have another patient do it, and we’re getting paid anyway.”

MTC denied this. “We do everything we can to recruit the best and the brightest, and to retain them,” Revell said MTC said it has returned money to the state when it has failed to fill critical positions, but declined to detail how much. The total staff is supposed to be 241; according to the audit, the overall vacancy rate is 23 percent and higher for guards.

Mississippi has paid the company at least $78 million to manage Wilkinson since the company took it over in July 2013, according to state data and the MTC contract, which calls for a payment of less than $43 a day per prisoner. Financially, the prison “is considered mediocre,” the audit says.

Three men locked inside Wilkinson, some of whom spoke with The Marshall Project using contraband cellphones, described witnessing bloody incidents and expressed fear that they, too, could die.

“Gangs control a vast majority of the decisions made in here,” one inmate said. “I’ve seen machetes. I’ve seen daggers.”

Over the course of six months in 2018, officers reported confiscating at least 170, including homemade knives ranging in size from 5 to 20 ½ inches; a 48-inch “spear-like” instrument; and a 6-inch toothbrush with a razor attached, according to a log kept by supervisors that was obtained by The Marshall Project. It describes nine assaults and three attempted assaults, including at least three stabbings that left prisoners with serious wounds.

Though MTC has not previously acknowledged the extent of the problems at Wilkinson, inmates have been complaining about conditions there for years; they called it the “killing field,” according to a 2014 report by the Jackson Clarion-Ledger.

That’s how it was for Brad Fitch. A native of the Gulf Coast, Fitch was 28 years old and on his fourth trip to prison, this time for aggravated assault. Since he first entered at age 18, he had spent less than six months outside, according to his prison records.

He had an extensive record of disciplinary problems at prisons around the state, including citations for drug use, threatening staff, and in one case allegedly telling a gang member to assault another prisoner, according to state records. Corrections officials identified Fitch as a member of the Simon City Royals, a largely white gang that is affiliated with the Gangster Disciples.

The two men seen attacking him on the security video, Dillon Heffker and Robert Williams, were also members of the Simon City Royals, according to investigative records, which indicate that the attack was related to the shooting deaths of two other gang members in 2016.

Federal prosecutors took over the investigation into Fitch’s death, according to the local district attorney. So far, no one has been charged.

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system, the USA TODAY Network, and the Clarion Ledger. It is published here with permission by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting.