Mississippi moonshot: Mississippi, her people played key roles in Apollo lunar landing, here are eight ways

Published 3:04 pm Friday, July 19, 2019

Fifty years ago this week, the world’s eyes were fixed to the sky as they considered the historic feat unfolding before them – for the first time in historic, humans were about to set foot on the surface of the moon.

NASA historians have calculated that some 400,000 Americans had some part in the historic Apollo program that took Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the lunar surface, touching down on July 20, 1969, making history.

Less than seven hours after they landed, Armstrong stepped onto the moon and made history again.

But few people may realize the incredible role Mississippi and some of her people played in that historic launch, landing and return.

Here are eight key contributors with deep ties to Mississippi:

No. 1: Mississippian Gilroy Chow, click to read his story.

Gilroy Chow, the son of a Cleveland grocer, spent his early years in the Mississippi Delta before moving to New York City with his family. He returned to Mississippi to earn a degree in engineering from Mississippi State. Chow got a job with Grumman Aircraft Engineering, a prime contractor for NASA. He was on the team that designed the lunar module that safely landed men on the moon and returned them back to the command module.

Later in the Apollo program, he was one of the engineers in the room when NASA had to quickly engineer a method to removed deadly CO2 gas from the Apollo 13 module after an Oxygen tank explosion.

“I was in the room when they threw all the parts on the table,” he is quoted as saying. “We did assemble the part because we had the flight equipment in Florida. We put the square peg in the round hole. I was there for that,” he said.

Chow worked in Florida where he helped train astronauts on how to fly the command, service and lunar modules.

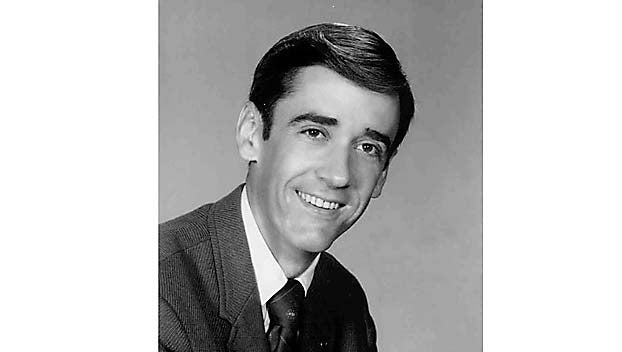

No. 2, Astronaut Fred Haise, click to read his story.

Fred Haise Jr., a Biloxi native, may be Mississippi’s most famous face connected to the Apollo space program.

Haise was a fighter pilot who logged more than 9,000 hours with the U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy before he joined the NASA’s ranks.

He famously was one of three astronauts aboard Apollo 13, the moon landing mission that nearly ended in tragedy when an oxygen tank exploded and nearly stranded the crew in space.

Haise was the backup lunar module pilot for missions Apollo 8 (first manned mission to orbit the moon) and Apollo 11 (first to land on the moon). He was backup spacecraft commander for the Apollo 16 mission.

Despite the shortened Apollo 13 and its aborted lunar landing, Haise remains in rare company – only one of 24 people who have flown to the moon. He later flew test flights of the Space Shuttle orbiter to test approach and landing procedures, but never flew into space on the Space Shuttle. He retired from NASA in 1979.

No. 3, Mission flight officer Jerry Bostick, click to read his story.

Jerry Bostick grew up in the tiny town of Golden, Mississippi, in Tishomingo County. He graduated with a degree in civil engineering from Mississippi State University and joined NASA in 1962. Bostick became the retrofire officer and flight dynamics officer during the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Skylab programs. He later held other roles at NASA as well throughout his career before leaving NASA in 1984 to work for Grumman Aerospace.

Bostick served as technical adviser for the film Apollo 13 and may have led to the famous line in the movie — which was never reportedly said in the real life events during the Apollo 13 flight — “Failure is not an option.”

Bostic was quoted as saying:

“As far as the expression ‘Failure is not an option”, you are correct that (NASA Flight Director Gene) Kranz never used that term. In preparation for the movie, the script writers, Al Reinart and Bill Broyles, came down to Clear Lake to interview me on “What are the people in Mission Control really like?” One of their questions was “Weren’t there times when everybody, or at least a few people, just panicked?” My answer was “No, when bad things happened, we just calmly laid out all the options, and failure was not one of them. We never panicked, and we never gave up on finding a solution.” I immediately sensed that Bill Broyles wanted to leave and assumed that he was bored with the interview. Only months later did I learn that when they got in their car to leave, he started screaming, “That’s it! That’s the tag line for the whole movie, Failure is not an option. Now we just have to figure out who to have say it.” Of course, they gave it to the Kranz character, and the rest is history.”

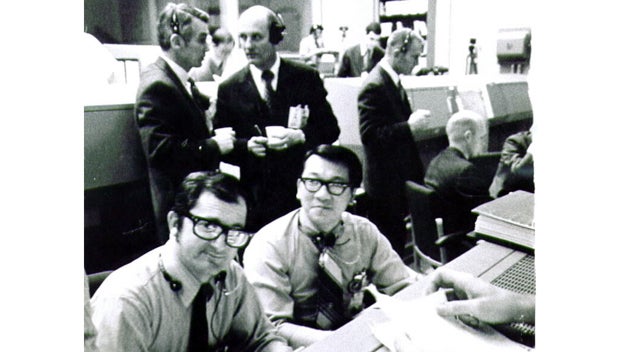

No. 4, Mission control officer Bill Moon, click to read his story.

Cleveland, Mississippi, native William “Bill” Moon was reportedly the only Chinese-American inside the Mission Control Center in Houston during the Apollo missions.

He worked as a flight controller. Moon, the son of Chinese immigrants, worked in his family’s grocery store starting at a young age.

He graduated from Mississippi State University.

He stayed with the Mission Control team into the early Space Shuttle flights.

He retired from NASA in 2002.

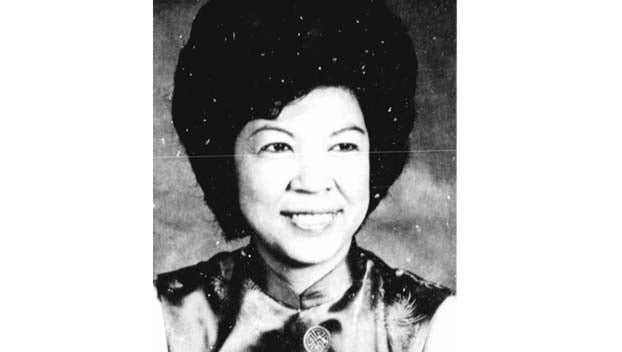

No. 5, NASA mathematician Josephine Jue, click here for her story.

Born in Vance, Mississippi, Josephine Jue began working at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston in 1963 as a mathematician.

Jue also worked as a compiler for Space Shuttle projects as well.

She was the very first Asian-American woman to work for NASA. She held numerous positions with NASA through her career.

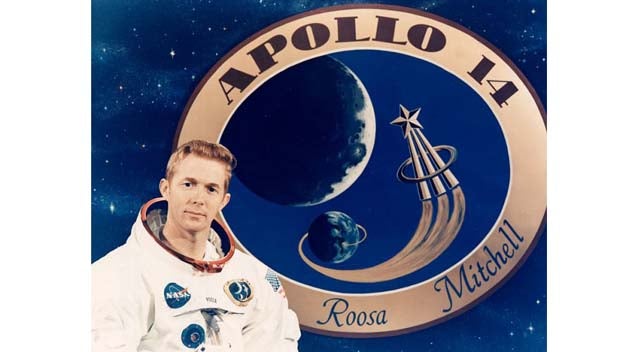

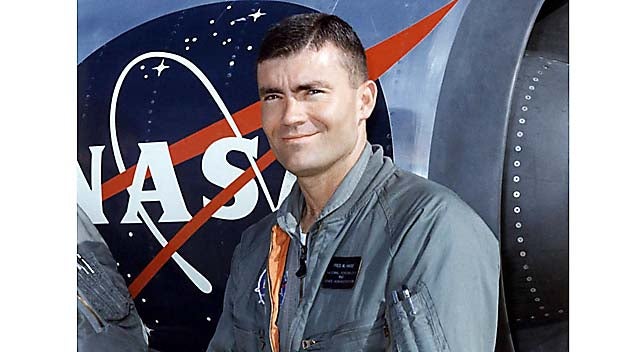

No. 6, Astronaut Stuart Roosa, click here to read his story.

A Colorado native, Stuart Roosa was a pilot and test pilot before being chosen as one of 19 astronauts selected to become part of the Apollo program in 1966. He served as part of the astronaut support crew for Apollo 9 flight in

Roosa was the command module pilot of Apollo 14 in 1971, when he traveled to and orbited the moon.

During Apollo 14, Roosa remained in orbit as fellow crew members Alan Shepherd and Edgar Mitchell landed on the lunar surface. He logged more than 216 hours in space.

After retiring from NASA, he chose to live on the Mississippi Gulf Coast and served as president and owner of Gulf Coast Coors, Inc., in Gulfport, Mississippi. He died in 1994 of complications of pancreatitis.

No. 7, John C. Stennis Space Center, where all manned Saturn flight rockets were tested.

Dozens and dozens of Mississippians worked at what was then called the Mississippi Test Facility in Hancock County as the Apollo program was getting underway.

At that location the powerful Saturn V rockets were tested. What is now called <a href=”https://www.nasa.gov/centers/stennis/home/index.html” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>John C. Stennis Space Center</a>, sits on the banks of the Pearl River near the Mississippi-Louisiana border. The site was key to testing and certifying the powerful rockets that took NASA astronauts to the moon.

From 1967 until 1972, Stennis test fired all first and second stages of the Saturn V rocket for the Apollo Program.

Michoud Assembly Facility manufactured the large rocket stages in nearby New Orleans. The stages were barged to Stennis. After testing, the stages were transported by barge once more, this time across the Gulf of Mexico to Kennedy Space Center, Florida, where they were prepared for launch on Apollo missions.

The first test firing on April 23, 1966, represented a “vital” milestone for the Apollo Program, NASA historians write. Altogether, Stennis conducted 42 tests for the Apollo Program, including ones on all of the engines used on the program’s manned missions. Apollo astronauts were safely transported the 240,250 miles to the moon by engines tested for flight worthiness in Mississippi.

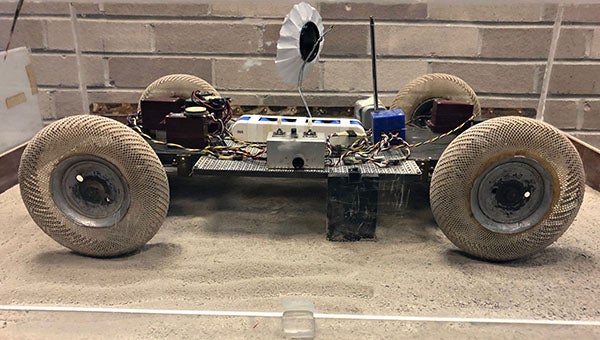

No. 8, the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center in Vicksburg

Before the Saturn V rocket that sent Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins on their way to the moon was launched, and before Armstrong took those famous first steps, the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center — known in 1969 as the Waterways Experiment Station (WES) — was involved with the Apollo Program.

Waterways’ involvement began with supporting plans to move the rocket to the launch pad at Cape Kennedy and ended with evaluating the wheels for the lunar rover, or “space buggy,” as it was called.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration used what was called a “crawler transporter,” a massive, 12.6 million-pound tracked vehicle that moved the Saturn rocket from the assembly building to the launch pad at a speed of 1 mph.

The road to the launch pad was, quite literally, paved in Vicksburg.

“Due to the massive weight of the crawler with the rocket on top of it,” ERDC historian Terry Winschel said, “WES was requested to do test evaluations on flexible pavements that would support that weight. WES did the flexible pavement evaluations for the road used by the crawler.”

Several months before the moon landing, Winschel said, NASA was already looking at future moon missions and investigating means for more detailed exploration of the lunar surface.

This time, WES helped develop the vehicle instead of the road.

“They were developing what we commonly call the moon buggy, but traction and wheels were a concern,” Winschel said. “The temperatures on the moon range from 250 degrees during the day, to minus 300 at night. Consequently, regular pneumatic tires that we use on cars and trucks wouldn’t work under such conditions. They had to find some other type of tire and wheel configuration.”

Based on the WES evaluations, a tire developed by Boeing and General Motors made of zinc-covered woven piano wire with titanium strips for traction was selected by NASA. The initial wheels, however, were too large and had to be reduced in size and weight.

The moon buggy made its first tour of the moon during the Apollo 15 mission in July 1971. Astronauts David R. Scott and James B. Irwin drove the 460-pound rover more than 17 miles around the lunar surface, at a speed of 6 to 8 mph.

The Apollo program ended with Apollo 17’s mission — the third to include a rover — in December 1972. No humans have been back since, but ERDC’s work with the space program has continued over the years.

More News