Unearthing a buried identity: Georgia professor fights for federal recognition of nearly lost Mississippi tribe

Published 11:06 am Wednesday, July 24, 2019

“You just tell everybody you’re white. You’ll have less trouble.”

Growing up, that is what Amanda Ealy’s mom told her whenever she asked what they were. Her racial heritage was shrouded in secrecy. No one would talk about it.

“You can look at my dad and tell he’s definitely not a white man, but he wouldn’t talk about it either,” said Ealy, now 51. “He would say, ‘We don’t discuss that.’ We weren’t allowed to talk about our color.”

That “color” was Native American, an identity that for generations has been stolen from Ealy’s people, either by society mislabeling them or by Ealy’s people choosing to suppress their identity in an attempt to escape the hostile racism and prejudice in their homeland of southern Mississippi.

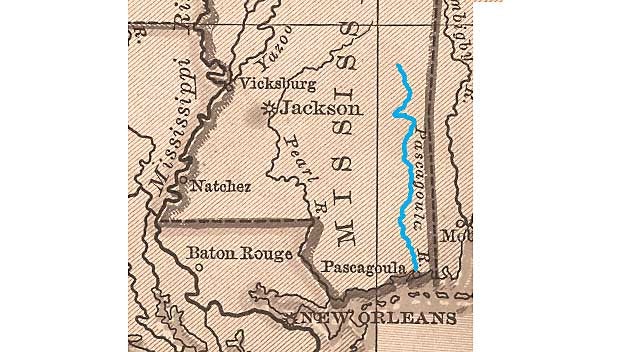

Ealy is part of the Pascagoula River Tribe, named after the body of water that winds through southeast Mississippi. Her people have lived in that area since at least 200 A.D. Now her contemporary tribe of around 900 people is in the thick of the monumental task of trying to get officially recognized by the federal government.

Recognition means the establishment of a government-to-government relationship between the United States and the tribe, acknowledging the tribe as a sovereign entity. It means access to better healthcare, education, and jobs for a tribe that is mostly blue collar and impoverished as a result of being relegated to the lowest rungs of society for hundreds of years.

But more importantly to the tribe, recognition means reclaiming who they are after decades of having Creole, black, white, or mulatto written on their birth certificates. It means taking pride in being Native American after seeing their parents and grandparents carry shame and embarrassment because the world around them told them “Native” meant less than.

The odds are against them. Since the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs implemented the current process of recognition in 1978, more than 360 groups have started the procedure. Only 18 have succeeded. Most do not even finish, and most that do finish fail.

It is a laborious process of data collection and bureaucratic hurdles that usually takes at least a decade to complete. For some tribes, it has taken more than 20 years.

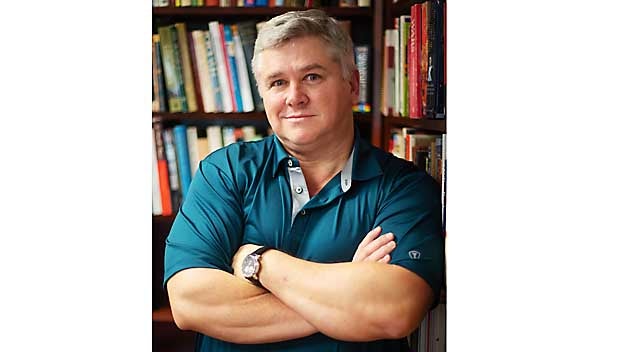

But what the Pascagoula River Tribe has that the other groups did not is Dr. Dixie Haggard, professor of history at Valdosta State University in Georgia who specializes in Native American history.

For the past six years, Haggard has worked with the tribe to trace their history and gather the mountain of evidence that the Bureau of Indian Affairs requires. He has crisscrossed Mississippi to interview more than 70 tribal members. He has scoured land records, court documents, school records, newspaper clippings, census reports, and colonial documents from the Spanish, British, and French — just about anything and everything he could get his hands on that mentions the tribe — to prove the tribe’s historical existence and right to recognition. His colleague, Dr. John Crowley, an associate professor of history at VSU who specializes in genealogy, has helped to verify the tribe’s lineage.

Most of Haggard’s research is in writing now, almost 200 pages, single-spaced. He is not taking any chances, he said, and is making sure every detail is included. Sometimes citations for one note take up a whole page.

“There are lots of groups that want to claim to be Indian that are not, so they had to be legitimate,” he said, referencing his decision to work with the tribe. “And they are. Their heritage holds up.”

A Quest For Adventure

Haggard, 55, is not part of the Pascagoula River Tribe. He is not even Native American. But his passion for Native American culture and history started when he was just a boy in the second grade searching the library shelves, looking for his next adventure.

“There was a small shelf of Indian books in my school library, but it was outside the easy section so I wasn’t allowed to check any of them out,” he said. “We had a 15-minute break in the mornings, so I would just go and read as many pages as I could in the 15 minutes and then put it back on the shelf and come back the next day. That’s the beginning of me being interested in Indian history.

“I liked reading about them because they were different from everybody else. There was a book on the Cherokees, the Sioux, and they’re all so unique. That’s probably something that makes me different from most people. I recognized that they weren’t all the same.”

Haggard studied history in college, and while pursuing a master’s degree, he decided to write his thesis on the military history of the Cherokee War, the conflict that unfolded from 1759 to 1761 during the French and Indian War. It was between British forces in North America and the Cherokees, two parties that had previously been allies.

His research allowed him to explain why the British, including a few American colonies, did what they did in the war, but one large question remained: Why did the Cherokees get into a war with their allies and do something that doesn’t make any sense at all from an economic, military, or political perspective?

The mystery followed him as he returned to school five years later to pursue a doctorate, and he eventually came to the conclusion that it had something to do with religion, which caused him to dig deep into the internal aspects of why Native Americans think the way they think.

This line of research led him into ethnogenesis, or how an ethnic group is formed, Native American identity, and how religion and other factors affect that identity.

Haggard’s association with the Pascagoula River Tribe came about in 2012 when he reconnected with childhood friend Sam Dart, a tribe member, at their 30-year high school reunion in Warner Robins, Georgia.

At this point, the tribe had been working off and on toward recognition since 1994 but had not gotten far. They needed a historian to help them make sense of their past and navigate the formidable web of requirements from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. They also needed an unbiased party to come in and tell just the facts to validate their story.

Dart made the request, and Haggard said he would look into it. He embarked on that mission in January of 2013 — a mission he describes as the hardest thing he has ever done in his life.

A Fight for Survival

Research from Haggard and tribal members shows that the Pascagoula River Tribe descended from the historic Pascagoula Indians, a tribe that archaeological evidence places as far back as 200 A.D. In the early 1700s, three women from the tribe intermarried with Frenchmen, a common custom that was meant to create connections between Native Americans and encroaching explorers.

Most of the tribe headed west in 1763, some settling in Texas while others went to Oklahoma. A small remnant stayed behind in Mississippi and multiplied throughout the 19th and 20th centuries as a couple of Choctaw and Creek people, as well as a number of white men, married into the tribe.

This resulted in the Pascagoula River Tribe, a people that has survived encroachments from the French, then British, then Spanish, then Americans. Today the tribe is highly assimilated. They do not have a reservation. They mainly live throughout six counties in southeastern Mississippi with lifestyles similar to many southern Americans.

You’re not going to see people dancing with feathers and all that kind of stuff,” Haggard said. “They are what I would call Christian Indians. They were Christianized probably from the very beginning when they were married into the French.”

Faith, Ealy said, is still a key part of the tribe’s DNA, as is survival and the ability to “hide in plain sight.” Agriculture and working the land is also a staple, along with a deep sense of community and family.

The interracial marriages throughout time have produced a tribe that is visually diverse.

“We come in all colors,” said Jackie Polk, Ealy’s cousin and secretary for the tribe’s council. “We are the definition of a contemporary tribe, and the reason why we’re so blended with color is because our identity was literally almost destroyed at onset, when those people set foot here and because we didn’t leave.

“That’s where the whole problem with our identity started. We weren’t pushed out. We kind of got quiet, stayed there on that little side of the river, where a Cherokee or a Choctaw got pushed farther along with their family and their tribe.

“Later on when those tribes traveled on the Trail of Tears and were pushed into reservations, what they took with them was a pure bloodline that stayed pure. They also took with them a grandmother or a grandfather who had experienced all of their culture and their traditions. Those things were passed down to the kids who went on that trail.

“We didn’t have that benefit. We were immediately inundated with outsider culture and traditions. Our bloodline started being diluted centuries ago. When you see a Pascagoula River Tribe Indian, you’re going to see a lot of different colors. It’s not always going to be your Indian-looking person with dark straight hair and dark skin. You could line up me and my four siblings and see that, while we have a lot of the same features, we’re all different colors.”

A Matter of Blood

“According to the federal government, being Native American means you have to be connected to a community,” Haggard said. “It doesn’t matter what your blood quantum is. It doesn’t matter what your ancestry is. Tons of people across the country have native ancestry. That does not make you Indian. You could be 100 percent native blood, but if you can’t show a connection to a historic Native American community, you’re not Indian in the eyes of the United States.”

The Bureau of Indian Affairs mandates, among a long list of other things, that a tribe seeking recognition must show that it had a community and government in place in 1900 and that it has maintained certain social institutions and connections every decade since then. The tribe must also show how many people have married within the tribe versus how many married outside the tribe and where the tribal members were living each decade from 1950 until now.

That means tracking down decades worth of documents and information and presenting it cohesively for the Bureau of Indian Affairs to review. The burden of proof is solely on the tribe.

“It’s a very complicated, and in some ways, convoluted, process,” Haggard said. “It’s the data collection and the evidence that’s so hard. It’s tons of data. One critique of the federal government and this process is that tribes like this have no resources. It’s an almost insurmountable process.”

But surviving against the odds is the Native American way. They have had no choice. When European colonists first set foot in North America, they brought deadly diseases that wiped out entire Native communities. They brought wars that ravaged their lands and homesteads. They even captured Native Americans and sold them as slaves to the Caribbean, providing the foundation for the African slave trade.

Haggard said early United States policy toward Native Americans was simple: Take their land and assimilate them. Forced removal and maltreatment was the norm, and the dying continued.

Researchers estimate that there were around 10 to 15 million Native Americans in North America in 1492. In 1900, there were 250,000.

A Painful History

Discrimination is woven throughout the stories of the Pascagoula River Tribe, from generation to generation, changing forms but remaining visceral.

Polk, 49, has read letters sent to her grandmother in the mid-1900s that denied her access to both the white and the black schools because of her race, leaving her confined to a small school for Native Americans that did not go past the eighth grade.

Polk, who has some features of a Native American but a lighter skin color, said her grandmother carried such shame about their heritage and the discrimination it brought. Her grandmother would touch Polk’s little pointed nose and say, “You need to get all the education you can, and just be thankful you’ve got that pretty little face, that pretty little nose.” Then she would touch her own nose and say, “Be thankful that it doesn’t look like this mug and that you don’t have this pug nose.”

Polk was a grown woman before she knew anything about what her grandmother and other ancestors had endured.

“I watched my dad struggle on an eighth-grade education to provide for five kids, and he did a fantastic job,” said Ealy, who is currently the chairperson of the tribe’s council. “As he grew older, he had illnesses because of the types of jobs he had to take. He did work with tractors and heavy equipment. Now they put you inside the heavy equipment and you get filtered air. But when he was doing that job, he pretty much dealt with the diesel fuel fumes. He struggled with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease because of that. I think that he might have had better opportunities if he had had more education.”

The tribe has been denied economic opportunity over and over again, Haggard said.

“They couldn’t get the better jobs because the better jobs went to whites,” he said. “Anything left over went to African-Americans. A lot of these people worked in the woods. They were farmers — charcoal, timber, lumber. Some of them were working on the railroads and had to work with creosol, which is used to preserve the logs. That stuff just burns your skin up, and I’ve seen guys that have scars on them from working with it.”

The term Creole, which historically meant a Frenchman born in the colonies, has haunted the Pascagoula River Tribe for decades as people have used it to ridicule the tribe. It often has been spoken with connotations of “mixed-breed” and inferiority, so much so that many Native Americans see the term as equivalent to the N-word, Haggard said.

Ealy put it simply when describing what it was like for her growing up as Native American in Mississippi in the 1970s and 1980s — “It was bad. It was very difficult.”

She and her siblings were picked on and teased constantly. Attending school after desegregation, they were the only people of color in their school. It was worse for her brother, who had darker skin. He got beaten up almost every day. He quit school and ran away often. He would go to relatives in a nearby town, sometimes living in the woods and sneaking in to eat because he was afraid of being sent back. He never felt like he belonged.

“When we were growing up, there was just so much negativity around the Indians,” Ealy said. “Every time you turned on the TV, there was some type of John Wayne movie and he was killing all the Indians because all the Indians were bad. So you didn’t want to be an Indian because they were pretty much getting killed. You were best just not talking about it.”

The pervasive stigmas and discrimination even led to racism between members of the tribe. When Polk was growing up, she said some members decided to turn their backs on their own people in an attempt at a better life.

“They were trying to be separated from something that was hindering them, hindering them from getting good educations and good jobs,” she said.

Treatment of Native Americans further complicates the recognition process in terms of evidence. Much was lost through the years of Removal. Eastern tribes were also not as well documented as tribes to the west.

There is also the problem of southern public officials assigning a variety of false racial labels to the Pascagoula River Tribe — sometimes accidentally, sometimes intentionally.

“In the South, specifically, because of Jim Crow, local authorities have tried to label them as African-American and hide their ethnicity,” Haggard said. “That’s part of the process that you have to deal with.

“You have some individuals who were mislabeled because they didn’t really know what they were. But in the South, there’s also this deliberate attempt by local authorities and by local populations to hide what they are, for various reasons.”

Several key pieces of evidence have helped Haggard and the tribe dispel the confusion. The tribe pops up on a federal record in 1902, when the government deployed the Dawes Commission to see if there were Native Americans who had not received land that they were entitled to as Choctaws.

But the tribe was not on the Choctaw rolls, which is what the government was using, so they were told to go home empty-handed. Yet that record of interaction is valuable proof because the Dawes Commission recognized the tribe as Indian — just not the right kind.

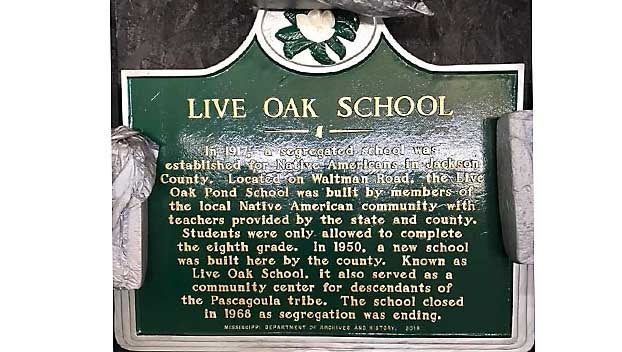

Other evidence proving the tribe’s existence since 1710 comes from their segregated Native American school; several “holiness churches,” which were planted throughout southeast Mississippi since 1938 as members moved to find work; and large family reunions that have occurred since the 1950s.

“Our identity has been buried and re-buried continually throughout time,” Polk said. “I’m angry because my family has been embarrassed. For me, it’s about the truth being told. That’s why recognition is important to me.”

There is still intense bitterness, Haggard said, throughout the nation’s Native American communities over their history as well as their present.

“There’s bitterness because they don’t understand,” he said. “There’s bitterness for what’s been taken. There’s bitterness for the way they’re still treated.

“But members of tribes deal with it in different ways. There’s significant diversity in that story because you’re talking about hundreds of tribes that are acknowledged. It’s a different story from tribe to tribe. There’s no such thing as one type of Indian.

“The public looks at them as just another minority group, but they are radically different and their issues are different. They all have their own relationship with the federal government. The only thing they have in common is having to deal with the federal government and with white outsiders.

“As far as the Pascagoula River Tribe, they don’t hold grudges for the most part. They’ve been discriminated against. There’s bitterness, and they’ll tell you about it, but most of the ones I’m working with are hopeful.”

A Final Push For Justice

Once the petition for recognition is submitted to the Bureau for Indian Affairs, which Haggard and the tribe hope to do soon, it will be reviewed by professional historians, anthropologists, and genealogists. Tribes usually wait two years for a decision to be made once the bureau begins to consider the petition — but that will not happen until the bureau has dealt with the other petitions already submitted.

Haggard has spent years working to help people who were complete strangers before this process started. His is compelled by the stories he has heard and the knowledge that, at this point, he is their only hope.

“They’re a legitimate group, but if they don’t have me, they’re not getting it done,” he said. “And they’re not going to get anybody else to do it. It’s just too hard.

“I’m kind of uniquely qualified for this group. I study southeastern Indians. I do identity and ethnogenesis. I have experience in colonial history. I do oral history. How many scholars are going to have these particular niches? There’s a very specific, unique set of skills that I have that, by coincidence, matches up with what this process needs for this group of people.”

“This may end up being my life’s work,” he added. “I may not do anything else even remotely as important — if we’re successful. That’s a big if. That’s the fear, putting a lot of effort into something and it fails.

“But I won’t be that disappointed because I failed; I’ll be disappointed because I didn’t deliver for them. I’ve spent time with these people. I’ve spent time in their homes. They are good people. They try to do well by each other and other people. If you see this opportunity to improve their situation, you have to help.”

If recognized, the tribe would not get any land, but any private land from tribal members could be turned over in trust to the federal government, meaning it could never be sold. They also would not receive any money, but they would have access to opportunities and resources for better education, employment, and healthcare.

“Families are already starting to get better education for their kids, but it’s hard,” Haggard said. “For people whose parents haven’t gone to college, it’s hard for them to go to college. Just staying in high school is a big deal.

“Some are pulling themselves out of poverty, but it’s a very, very slow process. That process would be sped up by becoming a tribe.”

While socioeconomic opportunity and growth is important to the tribe, resolving the issue of their identity is monumentally more important.

“On my dad’s birth certificate it says Creole,” Ealy said. “They’ve been denied who they are for years. They gave my people the title of Creole because they didn’t want to call them Native or Indian because that would come with certain rights. Just not having any racial identity is one of the biggest things for us.

“This is not about me. I don’t have any children. This is not going benefit me in any way. I will probably be dead before we see any benefits of this, and that’s OK, as long as our tribal people see some kind of dignity and respect and actually get to claim who they are.

“I’d like to see them be able to take Creole off their birth certificates and add Indian/Native American. That would be awesome. I’d like to take white off of mine and add Native American.”

Haggard’s research has already allowed the tribe to receive a historical marker from the Mississippi Department of Archives and History for the Native American school that their ancestors attended from 1950 to 1960. It was a significant event for the tribe.

“We just want the story told,” Polk said. “We want the truth told. We want our archives protected. We want to obtain artifacts we believe are out there. Our future holds a lot of promise.”

Polk said it is a great honor for her people that Haggard chose to tell their story and that he chose this endeavor, which she said is basically the “discovery of a tribe.”

“If it weren’t for him, in all honesty we would probably still be pushing paper and not have any real direction,” Ealy said. “I don’t even think that we would see recognition in our sights. We were just that disorganized. We’ve never been as far as we are right now. I actually see a light at the end of the tunnel.”

This article was written by John Stephen, a former newspaper reporter who now works at Valdosta State University in Valdosta, Georgia.