Mississippi man’s case could affect fate of hundreds of juveniles who face life in prison

Published 11:45 am Wednesday, October 21, 2020

By Shirley L. Smith

Mississippi Center For Investigative Reporting

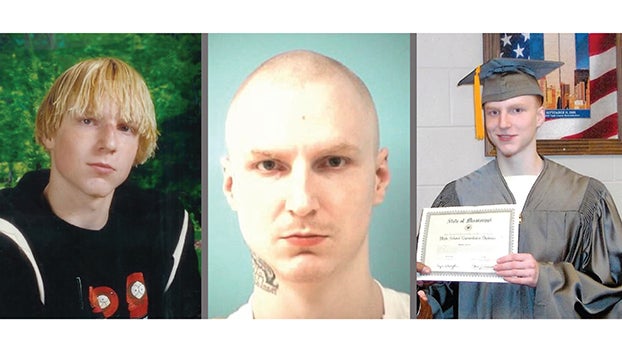

When he was 14, Brett Jones moved from Florida to Mississippi to escape his dysfunctional family life and a stepfather who allegedly emotionally and physically abused him from the time he was about 10.

Jones and his mother could not have foreseen then, in the summer of 2004, that he would end up in a far more sinister situation than the one he was fleeing, one that would forever change the course of his life and their family.

Now, 16 years later, Jones is at the center of a U.S. Supreme Court case that could affect the fate of hundreds of juvenile offenders across the country sentenced to die in prison.

In court hearings leading up to this case, Jones and his younger brother testified their stepfather, who married their mother in 1999, would grab them by the neck, choke them, and beat them with a belt buckle till the skin broke.

Their stepfather also used a Ping-Pong paddle to beat the boys and called them by derogatory terms like “little bastards” and “little motherf——,” Jones’ mother, Enette Wigginton, told the court.

“Me and my little brother, man, we were terrorized half the time just living there. You feel like walking through the living room when my stepdad was home was almost like dodging bullets,” said Jones, who like his mother, began cutting himself at an early age.

The animosity between him and his stepfather intensified after Jones said he missed a curfew, and his stepfather lashed out at him. He grabbed him by the throat, “pulled a belt” and threatened to “beat the s—” out of him.

This time, Jones fought back. He swung at his stepfather, “splitting” his ear, which bled “horribly,” Wigginton said. The police arrested Jones for domestic violence, and he was required to take an anger management class.

Shortly afterward, Jones went to live with his paternal grandparents in Shannon, Mississippi. Jones welcomed the move and said he was looking forward to starting high school, even though it meant changing schools again.

He had done plenty of that already. Wigginton said the family moved nine times in four or five years. “We moved around so much that the school lost all my records, and I had to repeat the seventh grade,” Jones said.

While in Mississippi, he enjoyed spending time with his cousins in a “normal” household, he said. “It was completely stress-free compared to what I was going through in Florida.”

But his newly found bliss came to a devastating end about two months later.

On Aug. 9, 2004, less than a month after Jones turned 15, his grandfather caught him in his bedroom watching television with his girlfriend, Michelle Austin, and ordered her out of the house. Austin had run away from her home in Florida and was secretly living with Jones as well as in a nearby abandoned fish restaurant.

Jones testified his grandfather Bertis confronted him later that day about the episode when he was in the kitchen making a sandwich. Jones said he “sassed” his grandfather, at which point the heated exchange escalated into a fight. He said Bertis pushed him, and he pushed back, then Bertis “swung at him.” Cornered, Jones said he threw the knife he had in his hand from making a sandwich, stabbing his grandfather. When Bertis continued to come at him, the record shows Jones grabbed a different knife and stabbed his grandfather eight times.

Jones said he tried to revive Bertis with CPR. When that failed, Jones tried to cover up the crime by dragging his grandfather’s body into the laundry room and using a hose to clean up the blood. He also “threw his shirt in the garbage under the sink,” and “attempted to cover up the blood spots in the carport by pulling his grandfather’s car over them.”

Jones said he called 911 and was waiting on an ambulance but panicked when the police arrived and left the scene in search of his grandmother.

At trial, Austin, who was charged as an accessory after the fact to murder, testified that Jones threatened to “hurt his granddaddy,” but under cross-examination, she acknowledged she was lying “to keep from going to the penitentiary.”

Jones told jurors he was afraid and stabbed his grandfather in self-defense. Unconvinced, they convicted him of murder. Under Mississippi’s parole statute, he was automatically sentenced to life without parole.

Hope For A Second Chance Quickly Crushed

In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that mandatory sentences of life without parole for juvenile homicide offenders are unconstitutional, because they violate the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against “cruel and unusual punishments.”

Justice Elena Kagan, who wrote the majority opinion, said: “Mandatory life without parole for a juvenile precludes consideration of his chronological age and its hallmark features — among them, immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences. It prevents taking into account the family and home environment that surrounds him — and from which he cannot usually extricate himself — no matter how brutal or dysfunctional.”

The court stopped short of banning all life-without-parole sentences for juveniles, but it said juveniles facing such a harsh punishment, which is equivalent to the death penalty, are entitled to a sentencing process that considers the unique circumstances of their case including their age at the time of the offense, family and home environment, the extent of their participation in the homicide and their possibility of rehabilitation.

In 2016, the court reiterated its position in Montgomery v. Louisiana when it ruled Miller should be retroactive.

These groundbreaking decisions gave Jones and other offenders serving mandatory life-without-parole sentences for a homicide they committed before they were 18, the right to have a new hearing to determine whether their sentences were permissible under the constitution.

Although Mississippi started applying Miller retroactively in 2013, ahead of several states, defense attorneys say Mississippi continues to unconstitutionally sentence and resentence juvenile offenders to life without parole.

“The circuit courts and the Mississippi Supreme Court are not following the law as outlined by the U.S. Supreme Court and so children are being sentenced to life without parole,” said attorney Stacy Ferraro, who represented many of these so-called “juvenile lifers” in Mississippi in their plight for freedom.

Jones’ resentencing hearing took place in 2015, about 10 years after he was incarcerated, but his hope for a second chance at freedom was quickly crushed. In the face of evidence of Jones’ efforts to improve himself in prison even though he had no incentive to do so because he was told he would never get out, then Circuit Court Judge Thomas Gardner III – the same judge who presided over Jones’ trial – resentenced him to life without parole.

“The United States Supreme Court announced a clear rule that you can’t be sentenced to life without parole for something you did as a child unless you are incapable of rehabilitation; unless you are so damaged that you can’t ever be saved, that you will always be a danger to society. Yet, Mississippi has completely failed to enforce that rule,” said Jacob Howard, legal director of the MacArthur Justice Center in Mississippi and a member of Jones’ defense team.

Marsha Levick, chief legal officer of the Juvenile Law Center who served as co-counsel on the Montgomery case, concurs. “It is very clear what Miller and Montgomery say and what they stand for, which is, that before you can sentence juveniles to life without parole today there must be a determination that they are permanently incorrigible,” Levick said. “And what happened in Jones’ case is that there was no determination that he is permanently incorrigible.”

Howard and Levick insist the purpose of the resentencing hearing is to determine which juvenile homicide offenders are capable of rehabilitation, not to relitigate the case. If the juvenile offender is not one of the “rare” juveniles for whom rehabilitation is impossible, then they said a sentence of life without parole is unjustifiable.

Jones’ attorneys argue that Jones is not a “hardened, incorrigible killer.” Before he killed his grandfather, they said, Jones did not have a history of violence other than the incident with his abusive stepfather, and he has evolved “from a troubled, misguided youth to a model member of the prison community.” The record shows that despite spending over a decade in prisons “rife” with gangs and violence, Jones has had “only one significant disciplinary incident.”

The U.S. Supreme Court will hear Jones’ appeal on Nov. 3.

In response to Jones’ appeal, Mississippi’s attorney general’s office said “no one wants to consider whether a juvenile homicide offender should serve a lengthy prison term or be sentenced to life without parole. But states must consider it — since states are responsible to their own citizens for protecting them, for deterring crime, for assuaging the victims, and for punishing the guilty.”

The U.S. Department of Justice and two victims’ advocate organizations filed briefs opposing Jones’ appeal, but several Justice Department officials, prosecutors and judges filed a joint brief in support of his case. Jones’ appeal has also garnered the support of over 70 organizations and individuals including Jones’ brother, biological father and his widowed paternal grandmother, Madge Jones.

In spite of losing her husband at the hands of her grandson, Madge has forgiven Jones. She is “steadfast in her belief that Brett is not and never was irreparably corrupt,” her attorney told the high court in support of Jones’ appeal

If Jones, now 31, loses his appeal, he would have one more chance to plead for mercy, albeit a slim one. Mississippi has a misunderstood statute that allows individuals, who have been sentenced to life, except those convicted of capital murder, to petition the sentencing judge or his successor for a conditional release after they reach the age of 65 and have served 15 years in prison, said André de Gruy, the state’s public defender. “This is not parole.”

Howard said, “The reality is that most juveniles who get a sentence of life without parole are going to be dead before they are 65 in Mississippi prisons. Even if they survive that long, requests for conditional release are seldom granted and thus do not provide a meaningful opportunity for release.”

Data obtained from the Mississippi Department of Corrections through a public records request show that since Oct. 28, 2015, three people have been released under the state’s conditional release statute. Two were 65 years of age, and one was 69.

The question before the U.S. Supreme Court in Jones’ case is: “Whether the Eighth Amendment requires the sentencing authority to make a finding that a juvenile is permanently incorrigible before imposing a sentence of life without parole.”

The answer to this question is expected to have national implications and resolve a split in the states’ appellate courts.

The Judge ‘Diminished His Humanity’

A 2019 article in the Harvard Law Review said: “Seven of the 11 state supreme courts that have directly addressed the question have held that imposition of (life without parole) on a juvenile homicide offender requires a finding of incorrigibility.” The Mississippi Supreme Court, on the other hand, and the supreme courts in Tennessee and Michigan have explicitly held that a finding of incorrigibility is not required. Virginia abolished life without parole for juveniles in February.

In response to Jones’ appeal, the state’s attorneys said, “Jones received precisely what the Eighth Amendment required: an individualized sentencing hearing where the sentencing judge considered youth and its attendant characteristics before imposing a life-without-parole sentence.”

At Jones’ resentencing hearing, his grandmother, mother, brother and cousin testified on his behalf. The hearing transcript, reviewed by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, shows Jones’ family corroborated his story about living with an abusive stepfather and a mother with a long history of mental illness who cut herself and abused alcohol.

The family described Jones as “smart,” a “good kid.” His mother said, “he was on the honor roll most of the time. His teachers all loved him. He was an excellent student.” However, Jones also struggled with mental illness.

Jones said at his resentencing that he sometimes heard voices, and he would cut himself with knives, razor blades and box cutters. He said he was prescribed medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two antidepressants when he was about 13, and an antipsychotic medication around January 2004 when he was 14. Jones and his mother said he abruptly stopped taking all his medication against medical advice when he moved to Mississippi.

The state pointed out in its argument to the U.S. Supreme Court that, “Jones did not introduce any medical records or offer the testimony of any mental health professional.”

When he first entered the Walnut Grove Youth Correctional Facility, where he was imprisoned from the age of 15 to 21, Jones testified he tried to kill himself and was on suicide watch for a few months. But after seeing a “psych doctor,” he said he learned how to cope and “it was better being in prison” than living with his stepfather.

Jerome Benton, a former unit manager at Walnut Grove, testified at Jones’ hearing, describing him as “a real nice kid” who sought out opportunities to work. He mopped floors and would do whatever was asked of him. “He was a very good employee,” and someone he looked upon like a son.

Gardner let Jones make a final statement following the hearing but only after already announcing his decision to resentence Jones to life without parole. By doing so, Levick said, the judge “diminished his humanity” and the value of what Jones had to say.

Nevertheless, Jones seized the opportunity to plead for mercy and a chance for redemption. “I’ve pretty much taken every avenue that I could possibly take in prison to rehabilitate myself,” Jones said. “I took anger management in prison. I’ve taken trades, got my GED (and) stayed in touch with my family.

“I’m not the same person I was when I was 15. Minors do have the ability to change their mentality as they get older … all I can do is throw myself at the mercy of the court and in front of the Holy Spirit.”

Gardner did not address Jones’ potential for rehabilitation before making his ruling. Although he acknowledged Jones “grew up in a troubled circumstance” with his mother “gone frequently for extended periods,” the judge downplayed Jones’ dysfunctional family life: “The conditions in that home are unremarkable except for the apparent unsettled lifestyle and an incident in which the defendant and his stepfather had a confrontation resulting from defendant’s failure to return home at the time set by the stepfather.”

Gardner concluded, there was “no evidence of brutal or inescapable home circumstances” because Jones was able to escape the home he was living in with his stepfather.

Lee County’s District Attorney John Weddle, who urged the court to resentence Jones to life without parole, said: “You got some kids out here who are in such bad situations that they feel like they can’t escape, and it clouds their judgment and they do very desperate things. In the Brett Jones’ case, however, we got a situation where he was removed from that situation, and he committed a murder not because of a desperate situation that he was in, but because of other things which in my opinion makes him more dangerous.”

Levick said juvenile offenders should be held responsible for criminal conduct, but justice policy should be driven by science, which shows that 90 percent or more of individuals who commit crimes when they were teenagers or “emerging adults” will naturally grow out of criminal behavior and become productive citizens.

In Mississippi, the two sentencing options for juveniles convicted of first-degree murder or capital murder are life without parole or life with parole. “Even if you get life with parole, it’s still a life sentence,” Ferraro explained. “That doesn’t mean you are ever going to get out. The parole board has a lot of criteria for releasing you, and so just getting parole eligibility is important, but it’s not like a get-out-of-jail-free card.”

People should not be punished for the rest of their life for a terrible mistake they made as a child, she said. “Most people are not sociopaths. There are probably a handful of people that should remain in prison, but it’s not the vast numbers that we have. All we are asking for is hope, just a little hope. That they could maybe, at some point, get out.”

This project was produced in partnership with the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Report for America corps member Shirley L. Smith is an investigative reporter for the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization that seeks to inform, educate and empower Mississippians in their communities through the use of investigative journalism. Sign up for our newsletter.

Report for America is an initiative of, and supported by, its parent Section 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization The GroundTruth Project (EIN: 46-0908502).

More News