In wake of George Floyd verdict, black caucus calls for investigation into Mississippi death

Published 3:42 pm Wednesday, April 21, 2021

By Jerry Mitchell

Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting

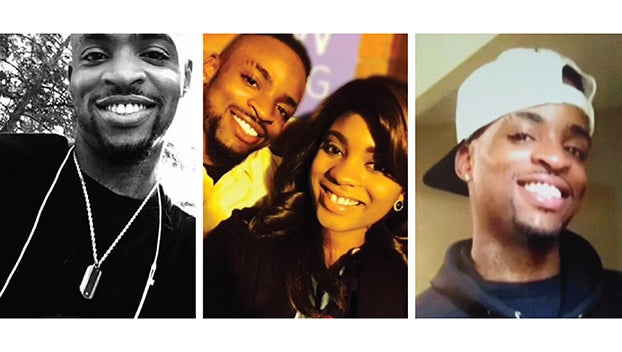

Mississippi’s Legislative Black Caucus is asking the Justice Department to investigate the 2018 death of Robert Loggins inside the Grenada County Jail.

“Given the grave concerns raised by the video depicting the law enforcement officers’ handling of Mr. Loggins, we urge an investigation,” state Sen. Angela Turner Ford, D-West Point, who chairs the caucus, wrote Wednesday.

The call for investigations came after the Mississippi Center of Investigative Reporting published a video of Loggins’ Nov. 29, 2018, death inside the Grenada County Jail. The video shows him slowly rolling from side to side when officers get on top of him inside the Grenada County Jail, with one officer appearing to kneel on his neck or head.

Three and a half minutes later, they got off him. The 26-year-old never moved again. More than six minutes passed before anyone checked his pulse or his breathing.

Despite that, the state of Mississippi concluded Loggins’ death was an “accident.” The alleged culprit? Methamphetamine toxicity.

After viewing the video as well as the autopsy report and photos, renowned forensic pathologist Dr. Michael Baden concluded the death was a homicide, saying the methamphetamine was very low and not a fatal amount. “They killed him by piling on top of him,” he said. “He absolutely died from some kind of asphyxia.”

MCIR has learned that the state’s pathologist may have never seen this jail video before ruling Loggins’ death an accident. The video wasn’t contained in the pathologist’s file on the case.

Citing the new evidence uncovered by MCIR, the Black Caucus called on the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation to reopen its investigation. The original probe concluded there was no foul play.

Loggins’ wife, Rika Jones, the administrator for his estate, has filed a lawsuit in federal court against those involved, accusing them of causing her husband’s wrongful death. The couple’s son is now 11.

Officers have yet to respond to the litigation, but they denied in interviews with MBI that they had done anything wrong.

Since 1995, the Justice Department has warned law enforcement officials that restraining people in the prone position increases the risk of death from asphyxia.

Adding weight to someone’s back adds to that risk, the report said.

In the jail video, several officers get on top of Loggins, and one officer appears to put his knee across Loggins’ neck or head.

Seth Stoughton, co-author of Evaluating Police Uses of Force, said it’s a general rule in policing to “avoid putting body weight on the neck or head. It’s even more well established that you do not do this while someone is restrained in the prone position. As soon as you get someone secured, you get them on their side.”

Despite these warnings, many officers have continued to use these restraints. The training manual for Grenada Police Department fails to warn officers about these risks.

More than a quarter century after the Justice Department’s warnings, several Minneapolis police officers got on top of George Floyd in the street, one of them, Derek Chauvin, kneeling on his neck for more than nine minutes.

“Mr. Floyd died from positional asphyxia, which is a fancy way of saying that he died because he had no oxygen left in his body,” Dr. William Smock, emergency room physician and police surgeon, testified in Chauvin’s trial.

Former Maryland Chief Medical Examiner David Fowler disagreed, saying he believed Floyd’s drug use and heart condition played a “significant” role in his death.

On Tuesday, a jury convicted Chauvin of second-degree murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. He could face up to 40 years in prison on the second-degree charge alone.

At 5:40 a.m. on Nov. 29, 2018, a woman in Grenada, Mississippi, telephoned 911, saying, “Someone’s in the back of my house calling for help. Please hurry.”

Five members of the Grenada Police Department responded: Capt. Justin Gammage, Sgt. Reggie Woodall, Cpl. Edwin Merriman, Patrolman Michael Jones and Patrolman Albert Deane Tilley.

They found a Black man face down with his arms tucked beneath his body. One officer recognized him as Loggins, who had battled both mental issues and a drug problem.

In bodycam footage obtained by MCIR, officers repeatedly asked Loggins to put his hands behind his back.

“Y’all going to kill me?” asked Loggins.

“Nobody’s going to kill you,” one officer replied. “We’re here to help.”

Loggins told officers, “My soul belongs to Jesus Christ, my savior, my protector.”

“Your ass belongs to us now,” one officer replied, and they used a Taser on him.

Records show officers used a Taser eight times. (Taser’s manufacturer warns that repeated blasts increase the risk of a heart attack.)

“Do it the old-fashioned way then,” another officer said. Yet another officer said, “Give me a baton. Give me a baton.”

Officers then grabbed him. Tilley said Loggins bit him on the hand. Bodycam footage showed officers striking Loggins with a flashlight.

“Robert Loggins was an unarmed man lying face down outside on a cold morning,” said his family’s attorney, Jacob Jordan of the Oxford law firm of Tannehill, Carmean & McKenzie. “He was incoherently screaming for help, quoting scripture, and asking law enforcement if they were going to kill him. He was clearly incapable of responding to verbal commands before the Tasing began.”

After handcuffing him, officers carried him to a carport, where the MBI report claims

“Loggins’ disorderly behavior” kept EMTs from conducting “a full medical assessment of Loggins.”

But bodycam footage paints a different picture. Asked about Loggins’ condition, an EMT can be heard saying, “He looks fine to me,” but the EMT never checked Loggins’ health.

The jail video obtained by MCIR shows that at 5:59 a.m., police and jail officers carried Loggins upside down into the lobby of the jail. They left him on the floor handcuffed and in the prone position. They never bothered to pull up his pants.

He seemed in distress, rolling from side to side, recalled shift supervisor Sgt. Edna Clark. “To me, he was trying to gasp for breath because he couldn’t breathe.”

She said she asked officers to take Loggins to the hospital but was waved off.

To get Tilley his handcuffs, officers and jailers piled on top of Loggins at 6:04 a.m. Tilley appeared to kneel on Loggins’ neck or head. When the officers got off Loggins three and a half minutes later, he failed to move.

“He’s lifeless,” Baden said. “This is why deaths occur in the prone position, and that’s what happened here.”

Clark noticed he was bleeding and called 911. The dispatcher replied that EMTs had previously checked him.

“He’s bleeding from his mouth. He’s bleeding from his legs,” she said. “I’m not gonna take him.”

At 6:14 a.m., Clark checked Loggins’ pulse and his breathing and called 911 again.

“This man has got no heartbeat, and he’s not breathing. I want them officers back over here. I want an ambulance,” she said. “Get them over here now.”

Four minutes later, EMTs arrived. They pounded on his chest in hopes of reviving Loggins, and when they couldn’t, they airlifted him to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

Five officers were placed on administrative leave with pay, but there were no charges and no known discipline. Police did not respond to requests for comment.

When an MBI investigator asked Tilley if his knee was on the neck or head of Loggins, he replied, according to the report, “Not to my recollection, no, sir. I don’t believe it was.”

“When you say you don’t believe, either you were or you were not,” the investigator responded.

“No, sir, I was not,” Tilley replied. “I was not on his head.”

But he never said whether he had his knee on Loggins’ neck.

Jerry Mitchell is an investigative reporter for the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization that is exposing wrongdoing, educating and empowering Mississippians, and raising up the next generation of investigative reporters. Sign up for MCIR’s newsletters here.

If you have any tips for our continued reporting on health care access in Mississippi, please email Jerry.Mitchell@MississippiCIR.org. You can follow him on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

More News