Alumni of Black school in Mississippi fighting for its history

Published 6:01 am Sunday, September 26, 2021

As with many Black schools in the Jim Crow South, references to Gulfport’s 33rd Avenue School in archives and books are scarce.

The school’s graduations and football games made the local newspaper, but almost never with photographs. Trophies, records and memorabilia were thrown out after the school closed with integration in 1969.

But the alumni remember.

They recall homecoming parades from the Quarters to downtown Gulfport, when the streets were lined with people — as many white as Black — eager to see the drum corps and the majorettes. They think about the band director, Willie Farmer, a strict disciplinarian whose rare smile was a source of joy. They remember the teachers they saw in church, who made home visits if they acted up, who shaped the school into a place of pride and rigor.

And now, they’re working to create a museum-style exhibit at the site of the school, which will become one of the few in Mississippi dedicated to the history of an African American school under Jim Crow. From the 1920s until 1969, the school educated thousands of Black children on the Coast, from as far away as Bay St. Louis and Wiggins.

The exhibit will be part of a $30 million Department of Labor-funded renovation of the building, which housed a Job Corps Training Center until Hurricane Katrina badly damaged it. Designed by a team of public historians from New Orleans, the exhibit will draw on oral histories with alumni and include images and memorabilia.

It will tell a story that many historians say has been neglected: How 33rd Avenue School, like Black schools across the South, provided a valuable education and a source of community pride in the face of racism and limited resources.

It’s different from the story of integration, and it deserves to be told on its own terms, alumni say.

Sandra Wyche, whose mother and her five siblings attended the school, recalled going to a meeting at the Gulfport Historical Society, where she met a woman who had lived in Gulfport for 65 years and never heard of 33rd Avenue School.

“You’re talking about people locally that didn’t know 33rd, didn’t know we were here, and that means they don’t know us as a group of people,” Wyche said.

MEMORIES OF 33RD AVENUE SCHOOL

When Charles Dubra remembers 33rd Avenue, he thinks about Mr. Farmer, who would wait until just the right moment during a football game to signal Dubra to start leading the band in a cover of a pop song on the radio.

“The beat would get going and the audience would get going and we would have it rocking in that stand,” said Dubra, who graduated in 1963.

Ruthie Thaggart-White, who graduated in 1956, remembers the school’s new brick building and business classes where she learned to type.

At the time, Mississippi’s School Equalization Program was increasing spending on schools for Black children in a bid to avoid integration, but historians have called it a “feeble” effort to convince outsiders that separate schools were equal.

In larger cities like Gulfport, however, schools for both Black and white children were better than their rural counterparts. Thaggart-White remembers what she did have much more than what she didn’t. As a drum majorette, she wore a white uniform and boots for the school’s popular parades. She also sang in the Glee Club and played for the school’s softball team, the Wildcat Babes.

“You never heard a student talk back to a teacher,” she said.

Jimmie Woullard, a member of the class of 1965, said that if you missed class, your teacher would come by the house to find out what happened.

Because professional opportunities for Black people in the Jim Crow South were so limited, Black teachers often had advanced degrees.

And by the 1950s, they knew that they were preparing their students for a new world, said Michèle Foster, a professor of education at the University of Louisville, who specializes in the histories of African American teachers.

The thinking could have gone like this, she said: “I’m looking at you and thinking, you’re gonna graduate in 60-something, and I’m preparing you for the opportunity that I didn’t have, that I think is on the horizon.”

INTEGRATION SHUTTERED THE SCHOOL

When the Gulfport School District announced plans to close 33rd Avenue and move its students in 1969, a PTA member fought back.

Wyvonne E. Daniels, the PTA’s secretary, asked the Department of Justice to step in and keep the school open, to serve white and Black children. The Black children already attending predominantly white schools were not being graded fairly or allowed to participate equally in social activities, she said.

The Daily Herald reported at the time that the DOJ’s civil rights division was sending investigators to Gulfport. But Daniels’ effort did not succeed.

Prince Jones graduated from 33rd in 1963. He came back to teach and coach in 1967.

He still remembers the day he walked out of 33rd for the last time, in the early summer of 1969. The tight-knit faculty were about to be dispersed across Gulfport’s previously all-white schools. Many of them had taught Jones. Now he said goodbye.

“I told them, y’all have a good summer,” Jones said. “’I hope that you enjoy your new assignment.’ Congratulating everybody. Letting them know we hope everybody is gonna be alright.”

Jones went on to work for the Gulfport School District for 40 years, winning 11 state championships.

But not all of his colleagues stayed with the district.

For many of the teachers at 33rd, their new positions were effectively demotions. The head coach Jones worked under at 33rd got a job in retail in New Orleans rather than serve as an assistant coach at Gulfport High. Another colleague left education and moved to Atlanta.

Across the South, about 40,000 Black teachers, many with advanced degrees, lost their jobs by 1970, as white superintendents decided white parents wouldn’t want them in the classroom.

Black children, too, suffered when integration became a one-way street. Wyche was set to attend 33rd Avenue School but was sent to integrate East Junior High School instead. She and other Black classmates endured a daily walk through white neighborhoods where people threw trash and sicced dogs on them.

“I didn’t have a problem with the integrating part,” she said. “I had a problem that they didn’t put the Caucasian kids into the Black communities.”

LASTING CONSEQUENCES FOR BLACK CHILDREN AND TEACHERS

The wave of dismissals of Black educators reverberates today. A 2014 study found that 82% of public school teachers are white, while students of color comprise about half of America’s public school kids.

Before the 1980s and 1990s, she said, there was relatively little historical research published on Black schools under segregation. But then, work by historians like Vanessa Siddle Walker, David Cecelski, Foster and others explored the experiences of Black teachers and students in segregated schools, and the roles the schools played in their communities across the South.

The stories historians have documented compliment contemporary quantitative studies showing Black students do better academically when they have Black teachers, Foster said.

“It took time before everybody could look back and say, there were positive things about segregation,” Foster said. “We couldn’t have a segregated society. But certainly we didn’t walk to the promised land. We got over there and there’s still a lot of issues.”

KEEPING THE MEMORIES ALIVE

The legally enshrined racism that led to the creation of 33rd Avenue School also makes finding material for the exhibit a challenge.

“We always say the archives are where white folks’ stuff is and the basements and attics are where Black folks’ stuff is,” Foster said.

“There’s nothing documented except by people like myself that are hoarders,” said Glenda Collins, a member of the class of 1963, who keeps boxes of newspaper clippings and photographs at her home about two miles from the school.

For the reunions that began in 1996, she compiled histories of the school.

“When searching for documented/recorded information with regards to our alma mater or former school, we’re still in a Hay Stack looking for the needle!” she wrote. “There is very little information to be found in the records of the Gulfport School District Administration office…. There are few records, no plaques, trophies or monuments, we only have our precious memories to remind us of the places where we received our first formal education.”

With so little information in more official sources and repositories, the mementos and documents held by individuals are precious.

In a typical museum exhibit, material culture — in the case of 33rd Avenue School, items like trophies, letterman jackets, school textbooks and photographs — helps tell the story. Cassandra Erb, the exhibition designer and manager, said she and her colleagues are trying to track down as many of those objects as they can.

“We’re building it from the ground up to find objects and images to tell the story that we’re trying to tell,” she said.

Oral history is also critical.

“The stories of the school really exist within the people,” she said.

UNTOLD STORIES OF BLACK MISSISSIPPI SCHOOLS

The project is unusual in Mississippi.

A Sun Herald review of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History database of historical markers found at least 24 markers for African American schools across the state. Several were among the South’s 5,000 Rosenwald Schools, built with funds raised by Booker T. Washington, philanthropist Julius Rosenwald and local Black communities.

But very few of the old school buildings have been turned into museum sites.

One exception is Hattiesburg’s Eureka School, which served students from 1921 until its closure in 1987, when the city belatedly integrated its elementary schools decades after Brown v. Board of Education. The space is now being transformed into a museum focused on the civil rights movement, but it will also include an exhibit about the history of the school, which is celebrating its centennial this year.

Latoya Norman, director of the Sixth Street Museum District for the Hattiesburg Convention Commission, said Eureka School had been a staple in Hattiesburg. When elementary schools finally desegregated, many Black community members expressed excitement.

“But not at the expense of Eureka having to close,” she said. “So I’m sure it was bittersweet.”

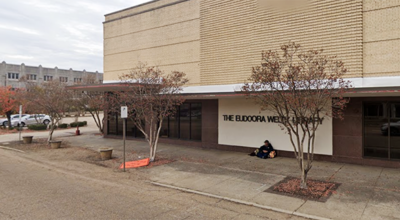

In early August, Erb and colleague Gaynell Brady, head of communications and project planning, held an event at the Biloxi Public Library. Alumni brought photographs to be scanned and objects to be catalogued.

Woullard brought a replica of his bright green letterman jacket. He played baseball and (initially against his mother’s wishes) football for 33rd Avenue School.

Thaggart-White brought a photograph of her class, then the school’s largest, and another from their 40-year reunion.

“Seeing is believing,” she said.

More News