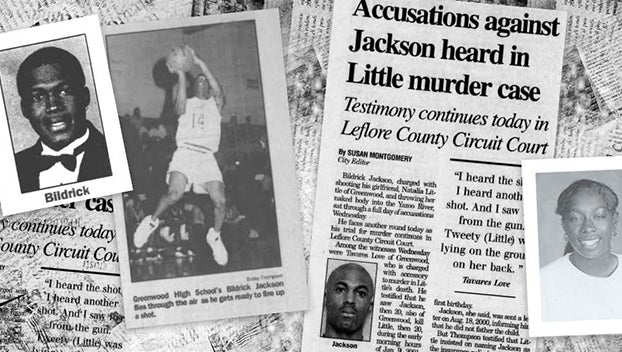

He’s Served 20 Years in Two Notorious Mississippi Prisons. Did This Murder Suspect Receive A Fair Trial?

Published 11:03 am Thursday, September 30, 2021

By the MCIR Journalism Lab

Imagine a murder trial in which there is no body, no murder weapon, and the prosecution’s star witness is suffering from such severe mental illness that the trial has to be postponed repeatedly.

That’s what Bildrick Jackson experienced at 23 when a jury convicted him of the 2001 murder of 20-year-old Natalia Little.

Now two decades later, he is still serving a life sentence with little hope of getting out.

The case: What happened?

Little’s sister, Isakina, a health care industry worker in Jackson, keeps a shrine of photos and candles for her younger sister, whom the family called “Tweety,” because they thought the newborn looked like Tweety Bird, the cartoon character.

Little, the “happy-go-lucky” one, dated Jackson off and on for six years.

In 1999, she gave birth to a son, Jaden. A paternity test determined Jackson was not the father, but he treated the boy as his own.

In late 2000, Little completed an application for a life insurance policy for $250,000, naming Jackson as the primary beneficiary and her son as the secondary beneficiary.

When Little left in the early morning hours of Jan. 9, 2001, Isakina babysat 18-month old Jaden. She later filed a missing person’s report on her sister. “She had never stayed gone that long before,” said her mother, Sheila.

Three weeks later, police charged Jackson with Little’s murder.

Body pulled from river, evidence disappears

A few months later, the remains of a human body were found on the west bank of the Yazoo River.

Authorities sent the body to pathologist Dr. Steven Hayne, who in turn sent the body to dentist and forensic odontologist Michael West.

West — whose identifications have resulted in some wrongful convictions — concluded the body’s teeth did not match Little’s, but what happened next remains a mystery.

“The body, the clothing and lab results were never saved,” said Kaelee Andrus, a criminal investigator working on the case. “Where they went no one knows.”

Judge: Witness’ mental illness has nothing to do with credibility

Much of the prosecution’s case against Jackson hung on the testimony of Love, who was diagnosed with bipolar illness and schizophrenia.

The defense tried to subpoena Love’s medical records, only to have the judge block the request, saying they were protected by the doctor-patient privilege.

Jackson’s defense attorney, Kevin Horan, told the judge the records were needed to attack Love’s “credibility, no different than if he was under the influence of drugs at the time of the alleged incident. …

“If this man is going to testify that these things occurred, we should be able to cross-(examine) him on … what his mental state was at the time and whether or not he has been under the care of a physician, whether he has hallucinated in the past, Your Honor. That’s something that this jury needs to know.”

The district attorney responded that this testimony would go to character, which was excluded under court rules.

The judge sided with the prosecution, saying this had nothing to do with Love’s credibility. The Mississippi Court of Appeals and the Mississippi Supreme Court agreed.

With the jury out, Love testified that he had never suffered any hallucinations, but a 2002 evaluation of Love’s mental condition, obtained by MCIR, shows he indeed suffered “delusions and hallucinations” and that he often failed to take the drugs that doctors prescribed.

Some other trials have allowed such cross-examination.

During the 1994 trial of Byron De La Beckwith for the murder of Medgar Evers, prosecution witness Peggy Morgan testified that Beckwith had bragged about killing Evers, saying that he wasn’t “scared to kill again.”

The defense sought to undermine her credibility. Under cross-examination, she acknowledged that she remained on medication for an anxiety disorder because of her horrific past: she suffered from child abuse, she witnessed incest, her father was murdered, and her mother froze to death.

Key witness gives conflicting versions

At trial, Love testified that he and Jackson gave two women a ride home from work on the evening of Jan. 8, 2001, and then went to a dance at Mississippi Valley State University.

When the dance ended at midnight, they picked up Little and began riding around, he said.

On their trip from Greenwood to the Rising Sun community, Love said Jackson asked Little which places looked good to dump a body.

He said Jackson asked him to stop the car to use the bathroom and afterward he called out for Little, who got out of the car.

“I was changing my tape on my tape player, and I heard a shot,” he said. “I heard another shot and I lifted my head up, and I saw fire coming from a gun two times.”

Love said Jackson returned to the car and said, “Let’s go.”

Love testified that he saw Little’s body on the ground and later saw Jackson throw his gun into the river.

After that, Love said they went home, only for Jackson to knock on his window hours later, saying he needed help moving the body.

Love testified that he dropped Jackson off on the road where he had killed Little, and when he returned, Jackson had loaded a garbage bag with what he said were Little’s clothes.

“So he got in the car,” Love said, “and we put the clothes — he put the clothes in the dumpster” behind a convenience store in Greenwood.

When they were done, Love quoted Jackson as saying, “Man, we have to go move the body.”

He said Jackson put her body into a garbage bag and that he helped Jackson load the body into the trunk. (In his original statement, Love made no reference to garbage bags.)

When they reached the river, Love said he helped Jackson throw her body off the Walthall Street Bridge.

Authorities never found the gun, Little’s clothes or her body. Little remains missing.

Love testified both he and Jackson had blood on them — a detail missing from his statements to police.

“You testified you were wearing a jacket that night?” Horan asked.

“Yes,” Love replied.

“Had blood all over it?”

“Yes.”

“There was blood on your clothing?”

“Yes.”

But he testified that police only tested his jeans and shoes.

He said there was blood in the trunk, and they had to wash it out.

“How big a spot was it?” Horan asked.

“Couldn’t see no spot because the car was dark, so it was wet looking,” Love replied.

Authorities make no reference in their reports to finding any traces of blood.

Weeks after Little’s disappearance, police questioned Love, who gave different statements. “I was scared,” he said, “because I thought Bildrick would kill me because he had already killed Tweety.”

Under cross-examination, Love admitted he had told police this.

“You told this jury the reason that you changed your story so many times was because you were scared when, in fact, you told them you were scared the first time you talked to them?” Horan asked.

“Yes,” Love replied.

Love told jurors that Little was wearing an orange coat.

Asked what he was wearing, he didn’t recall. Asked what Jackson was wearing, he didn’t recall.

Love led authorities to the place where he said Jackson had killed Little.

By now it had been weeks, and authorities said they gathered what they believed was blood from the dirt, despite the half dozen inches of rain that had fallen since. The State Crime Lab matched the mitochondrial DNA to Little’s family.

After deliberating two hours, a jury convicted Jackson.

Deal lets supposed accomplice walk free

Love never spent a day behind bars.

Three months after the trial, authorities dropped his accessory to murder charge. After pleading guilty to the lesser crime of being an accessory after the fact, he got five years of house arrest.

On appeal, Jackson questioned his lawyer’s failure to cross-examine Love about any deal he made with the state, which “incorrectly allowed the jury to accept Love as a witness who had no reason to lie.”

But the state Court of Appeals concluded in its 2005 decision that because Love’s plea agreement wasn’t part of the official record, “Jackson cannot claim that his trial counsel’s failure to ask Love about any deals he made with the State constituted ineffective assistance of counsel.”

The insurance policy that Love maintained was the reason that Jackson killed Little went instead to her family, which was represented by a lawyer from the prosecutor’s office.

‘Like living in the Twilight Zone’

These days, Jackson endures his time inside the Marshall County Correctional Facility with more than 800 other inmates.

“It’s like living in the Twilight Zone, where things don’t make sense,” said his wife, Cherae. “It’s hard to watch him suffer. If he had done something, he’s willing to do the time. But he says, ‘I didn’t do anything, and I have to stay here.’”

She attended high school with Jackson, and the couple reconnected five years ago. They married in 2018.

“It felt like God said, ‘Step out in faith and I’ll take care of the rest,’” she said. “He deserves to be loved.”

Jackson isn’t eligible for parole until he’s 65. In the meantime, she will wait for him, praying he wins on appeal.

“God’s going to make a way,” she said. “They make him out to be a monster, and he’s not. He’s a very kind-hearted person.”

Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting is a nonprofit news organization that is exposing wrongdoing, educating and empowering Mississippians, and raising up the next generation of investigative reporters. Sign up for MCIR’s newsletters here.

More News