These courts are making a difference for domestic violence victims. There are only 3 in Mississippi.

Published 3:15 pm Thursday, November 11, 2021

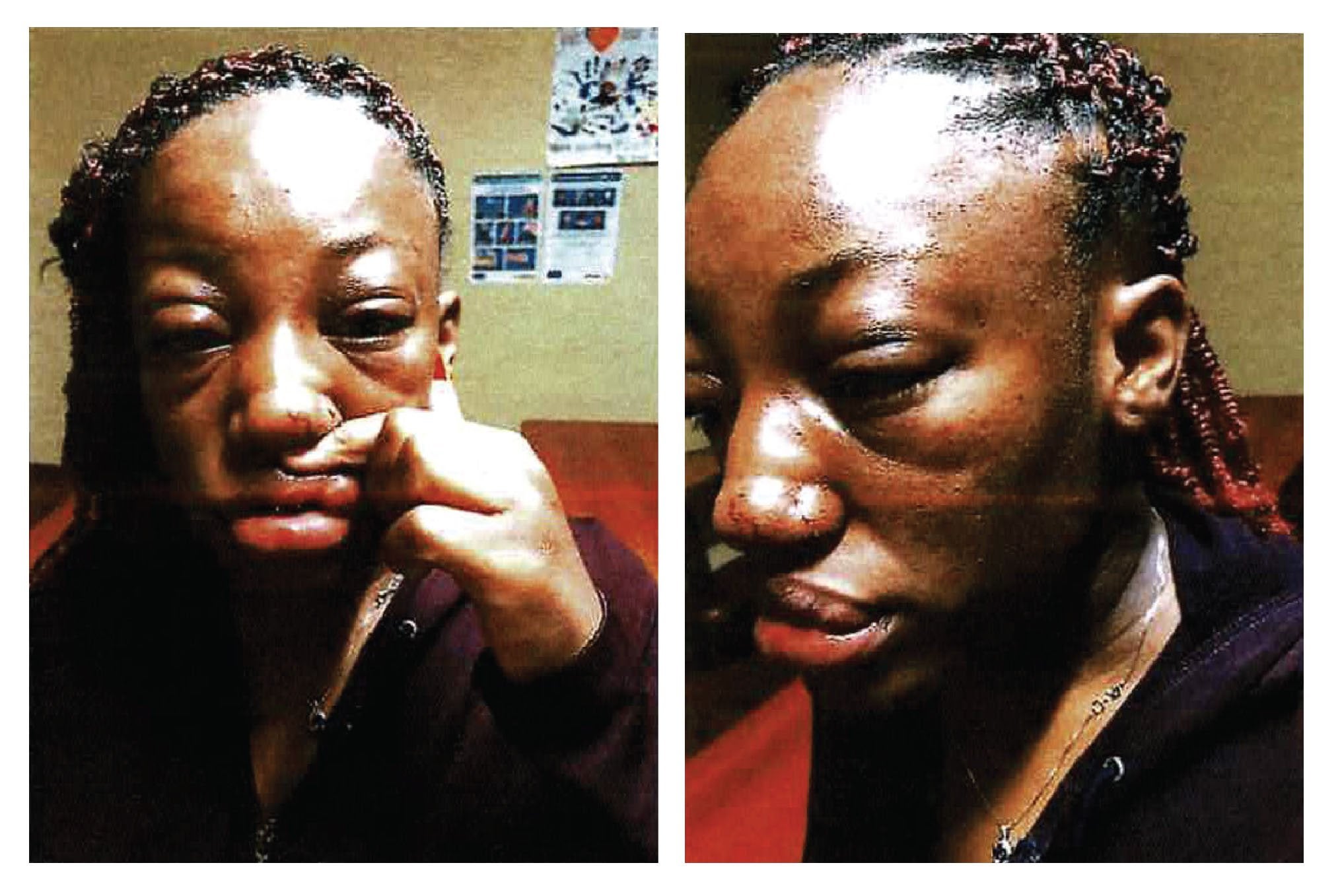

- In November 2020, Vicksburg police documented injuries Akima Adams had suffered at the hands of Daron Evans. (Vicksburg Police Department)

By Ann Marie Cunningham

Mississippi Center For Investigative Reporting

Dressed in neat scrubs, Akima Adams, 23, stood small and slight before the judge.

“This is the second time you’ve been in this court, right?” asked Judge Angela Carpenter, as she presided over Vicksburg’s domestic violence court.

“Yes,” Adams said in a voice barely audible over the microphone.

To Adams’ left was her former boyfriend, Daron Evans, 25, wearing convict’s stripes and shackles. Standing nearby was Sgt. Kathryn Trueheart, who had investigated both of Adams’ complaints against Evans.

Evans first appeared before the court on Nov. 10, 2020, on a charge of domestic violence. In the photos Vicksburg police took of her injuries, Adams is unrecognizable. She had not wanted to testify in court; she asked that Evans be ordered to get help.

Carpenter accepted Evans’ guilty plea but withheld sentencing until he completed anger management counseling through a Vicksburg ministry. The judge also ordered him to enroll with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs for psychological counseling and evaluation. He failed to do so. As a result, he was convicted of domestic violence and sentenced to three days in jail.

Carpenter, a municipal court judge who presides over the domestic violence court held twice a month, asked Adams to describe why she had come to court this time. Very softly, Adams described how Evans had come to her apartment and threatened her with a gun.

“Ever since I told him I didn’t want to get back together with him,” Adams said, “he’s upset with me.”

He demanded money for furniture they had bought as a couple. Followed by Evans, Adams drove to the bank, but called the police en route. Adams got an order of protection.

In April 2021, Adams complained to Vicksburg Police Chief Penny Jones that she had seen Evans passing by her home frequently, a worrying sign. Young women like Adams, those 24 or younger, are more likely to be stalked and killed, according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

On the night of April 20, Evans had shown up again at Adams’ apartment, beating on the doors and windows. He tore the side mirrors off her new boyfriend’s car. Then he fired four gunshots in the parking lot. Adams called the police.

Evans was arrested on a contempt of court charge and on Adams’ second complaint.

Carpenter noted that the former couple’s 2-year-old son was in the upstairs apartment with Adams’ mother when Evans began yelling, banging and firing outside Adams’ home that day. Research has found that violent experiences can leave lifelong effects on children.

So, the judge said she was adding to Evans’ prison time and fine. He was found guilty of a second misdemeanor domestic assault charge. If arrested again, he’ll be facing a felony. He was fined almost $725, and sentenced to 10 days in jail — the severest sentence the judge was observed to hand down during a two-month period.

In Vicksburg, a city of about 22,000, almost everyone associated with the domestic violence court is Black, and some are survivors. Like Akima Adams, most victims who appear in the city’s domestic violence court are low-income, Black women, aged 21 to 40. Many arrive in court in t-shirts and jeans. Often the only White person in the courtroom is the bailiff, Lt. Claude Billings, who says, “I don’t know why a man would hurt a woman.”

Like Judge Carpenter, prosecutor Kim Nailor, investigator Trueheart, social worker Linda Sweezer, victim advocate Krystal Hamlin, court administrator Kayla Hudson, and two court clerks present are Black women.

After appearing before Judge Carpenter, Adams had to fill out an anonymous questionnaire about her experiences with the city justice system. She wrote she would welcome a program that would help her and her son with the psychological aftermath of their experiences with Adams.

Adams lives in a modest neighborhood of shotgun houses and cottages. Her apartment building is a small two-story square. “It was terrifying,” she said of hearing Evans firing his gun outside. “It comes back to me,” she said. Now her son with Evans “is stand-offish” with his father.

The Violence Against Women Act At Work In Vicksburg

Vicksburg’s domestic violence court is the federal Violence Against Women Act in action. (VAWA is expected to come up for reauthorization in the U.S. Senate this fall. Advocates have been holding regular Days of Action to lobby senators.)

Besides Vicksburg, two other Mississippi cities have domestic violence courts: Jackson and Hattiesburg, which announced Oct. 21 that it is inaugurating one. State Rep. John W. Hines Sr., whose district is in the Delta, is trying to establish a fourth in his hometown of Greenville by introducing a bill in the state Legislature. He is not optimistic: “Any bill introduced to the Mississippi State Legislature by a Democrat goes nowhere.”

Vicksburg’s court is the only one in Mississippi that is part of a coordinated citywide effort to combat domestic violence. As such, it is a model. Women of color are more likely to suffer domestic violence, and Vicksburg’s Beverly Prentiss Domestic Violence Victim Empowerment Program, while not limited to a specific race, represents women of color helping each other.

Starting in the 1980s, some states and cities launched domestic violence courts as a means to avoid seeing the same offenders over and over again, and to deliver more consistent verdicts for domestic violence. In 2010, a report by the National Institute of Justice found 208 courts nationwide, most in big Northeastern, Midwestern, and Western states, including California, Illinois and New York.

Today, several Deep South states have domestic violence courts. Nationwide, according to the Center for Court Innovation, some states even have “mentor courts” for fledgling domestic violence courts.

In 2010, Vicksburg’s city lawyer, Nancy Thomas, then a municipal court judge, said she was finding “domestic violence victims often wouldn’t come to court because they were afraid to be in the same room as their abusers. If victims did show up, they might be too frightened to speak.” Thomas knew municipal court records also needed a database for civil protection orders. “Records were being kept as hard copies and in notebooks. Finding relevant information about offenders was very difficult.”

There was no counseling for victims, or an advocate or agency to guide them through civil or criminal court systems, and no way to ensure offenders were held accountable to court orders forbidding them to contact victims. Thomas said she knew that, without guidance, “traumatized victims might give up and go home to situations that were dangerous, even life-threatening.”

Although VAWA does not specifically fund courts dedicated to domestic violence, the law does offer local municipalities grants for “services.” Working with Judge Toni Walker Terrett, now a Warren County circuit court judge in Vicksburg, Thomas applied for and was granted federal VAWA funds, matched by state and local monies, to set up the Vicksburg Domestic Violence Victim Empowerment Program.

Vicksburg Police Sgt. Beverly Prentiss, a member of the department for more than 35 years, had overseen domestic violence investigations. When she died in 2020, the Victim Empowerment Program was renamed to honor her. Chief Jones, herself a domestic violence survivor, gives Prentiss credit for training her and her male predecessor, along with other officers to respond to domestic violence, and to maintain a “zero tolerance” policy towards it.

Today there are about 300 domestic violence courts nationwide. The only evaluations of their effectiveness have been local. In the early 2000s, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Violence Against Women set up a Judicial Oversight Demonstration Initiative to evaluate domestic violence courts in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin; Dorchester in Boston; and Washtenaw County, Michigan, whose seat is Ann Arbor. Like Vicksburg, the first two sites have large Black populations. The initiative reported that coordinated efforts like Vicksburg’s, where police, courts and victim advocates work together, have the best results: less recidivism and reduced incidence of domestic violence.

In 2013, the Center for Court Innovation evaluated New York State’s domestic violence courts, and in 2017, three researchers carried out an analysis of existing studies of these courts. Both studies came to the same conclusions as the earlier Justice Department study.

A Difference For Vicksburg Victims

Every October, Domestic Violence Awareness Month, posters in Vicksburg remind non-uniformed police and court staff to wear purple. Vicksburg’s Haven House Family Shelter organizes an annual walk called Breaking the Silence on Domestic Violence. Besides offering emergency shelter, Haven House helps survivors with counseling and affordable housing.

Chief Jones has her own nonprofit, The Peni Center Inc., which teaches women how to compose a resume, how to work on a computer and how to balance a checkbook, along with other skills necessary for their financial independence. Judge Terrett holds a monthly “Hour of Power,” a noontime public information gathering for women on the Warren County Circuit Court lawn. October’s Hour included staff from the Mississippi Coalition Against Domestic Violence, breast cancer screening, and a lunch truck that was an example of a woman-owned business.

At the 2021 walk on Oct. 2, Jones announced that over the past year, the Vicksburg police had made 208 arrests for domestic violence. Krystal Hamlin, outreach coordinator for Haven House, reported that in 2020, she and the house staff had served 66 residents in the shelter’s 22 beds.

Based on those statistics, reports to police of domestic violence and arrests in Vicksburg have decreased significantly since Thomas and Terrett applied to VAWA. Their grant application noted reports of domestic violence to Vicksburg police reached a high in 2007 of 864 with 383 arrests. From 2007 to 2009, the average number of domestic violence arrests in Vicksburg was 371 per year.

Police often dread responding to calls about domestic violence: They are not eager to face distraught couples and abusers who may turn their violence on officers. Every October, all Vicksburg police undergo a day-long refresher course on how to respond to these calls. They learn how to defuse volatile situations and determine what happened, even if the victim does not want to cooperate or press charges.

Sgt. Trueheart says she has never fired a gun, though she has investigated three murder-suicides. She describes Vicksburg’s domestic court as “a smaller, intimate setting. Often the victim doesn’t want to tell her story in front of a whole crowd.”

How Domestic Violence Court Works

Two months of regular attendance at Vicksburg’s domestic violence court saw tears, high emotion and descriptions of a variety of abuse, along with screams from the convicted of “I ain’t done nuthin’!” Offenders included a mother who had struck her adult daughter in the head in Kroger’s–captured on the store’s surveillance camera–and a teenager who had forced the pickup driven by her straying boyfriend onto a highway median.

With the accuser and accused before her, Judge Carpenter begins with a hearing to determine if there should be a trial, and whether the victim needs a temporary or permanent order of protection.

The judge works closely with prosecutor Nailor, who prepares by researching the case and wherever possible, looking for mitigating circumstances or details that may explain what happened. Nailor began in private practice, where she represented a client abused by her husband. The weekend after the divorce was granted, the ex-husband killed her client and then committed suicide. Nailor was aware that the most dangerous time for a victim of domestic violence comes when she decides to leave, and had cautioned her client. Today, Nailor becomes tearful when she recollects the case: “She came to my office and signed her divorce papers on a Friday. On Saturday, she and her girlfriends were going out to celebrate. She kept saying, ‘I just want to live.’ Early Monday, I got a call that he had killed her.”

During those two months of observation, Carpenter usually accepted Nailor’s recommendations for sentencing. Very often, Carpenter requires offenders, including the teen and the mother, to undergo counseling and/or courses in anger management and return to court to describe what they have learned.

When court is in session, social worker Linda Sweezer, the counselor who works with offenders, is almost always in the front row. Anger management classes are conducted by the Rev. Charles Truly, whose Truly Ministries has worked with offenders for more than 20 years.

Sweezer agrees that Nailor and Carpenter work well together. Their smooth partnership, she said, is one reason for the Vicksburg’s court’s success.

To supplement the court’s work, Carpenter wants to introduce new programs, including a roundtable where anyone can present ideas. Other possibilities include a hotline or other forms of help for offenders, and education for victims and survivors on the effects of trauma from domestic violence, and how to mitigate them. One mother who had appeared in domestic violence court said of her children, “They’re boys. They’re resilient.” But perhaps not.

Vicksburg may have even more to offer. Nancy Thomas says, “We can’t get burnt out on this issue.”

This story was produced by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting. Ann Marie Cunningham is MCIR’s Reporter in Residence. She holds a 2021 grant from the Domestic Violence Impact Reporting Fund at the Center for Health Journalism at the Annenberg School of Journalism at the University of Southern California. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.

More News