Thousands jailed for long periods waiting to go to trial in Mississippi

Published 10:42 am Wednesday, January 12, 2022

Thousands of people in Mississippi continue to be jailed for long periods while waiting to go on trial because they are too poor to afford bail, judges may deny bail altogether or public defenders might not be available when they’re needed, according to a new report from a group that advocates for the rights of the incarcerated.

The report released Wednesday by the Roderick and Solange MacArthur Justice Center at the University of Mississippi School of Law says that as of the fall, about 2,700 people had been held longer than 90 days in county jails. Of those, more than 1,000 had been jailed at least nine months and about 730 had been jailed more than a year.

The problem is likely much more extensive because counties were inconsistent in reporting information about who is being held for long stretches before trial, said the center’s director, Cliff Johnson.

The new report is the fifth issued by the center since April 2018 about long pretrial incarceration.

“The law and our criminal rules say that there is a presumption of release prior to trial and that requiring payment for one’s freedom should be the exception rather than the rule,” Johnson said in the news release.

Johnson said Mississippi judges “demand that people pay for their liberty” in most felony cases.

Mississippi, Arizona, Pennsylvania, South Dakota and Washington are the only states without a statewide system of public defenders, according to the MacArthur Center.

In Mississippi, the expenses for public defenders are paid by local governments, and Johnson said about 85% of criminal defendants in the state are represented by public defenders. He said the system is inadequate because the first attorney appointed for a defendant usually handles only preliminary matters. He said no other public defender is appointed until after a person is indicted.

Johnson said the “dead zone” between preliminary court appearances and the time of indictment can be lengthy, and evidence that could clear an accused person could be ignored during that time.

Mike Carr works as a public defender in the impoverished Delta region, in addition to handling cases in private practice. He said judges often assign attorneys with little criminal-defense experience to do public defense work.

“The people who suffer the most are, of course, the poor,” Carr told The Associated Press. “The poor have to rely on a patchwork system of county-funded, part-time criminal defense attorneys that can make more money handling private cases.”

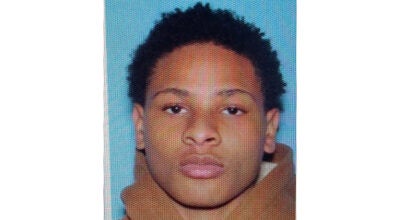

Carr said one of his public defense clients, Recardo Frazier, was arrested in June 2015 on murder and weapons-possession charges in Coahoma County, and a judge denied bond. Frazier remained in jail in a neighboring county until he was brought to trial in February 2020. Carr said jurors could not reach unanimous agreement on a verdict, so the judge declared a mistrial.

After the trial, a judge set bond and Frazier was released from jail. Carr said Frazier is awaiting another trial, and that has been postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.