‘It took a lot of courage.’ Mississippi leaders reflect on events that led retirement on state flag with Confederate emblem.

Published 3:46 pm Thursday, March 3, 2022

In June 2020, the flag of the State of Mississippi bearing the confederate battle emblem was retired after being the state’s only flag since 1894.

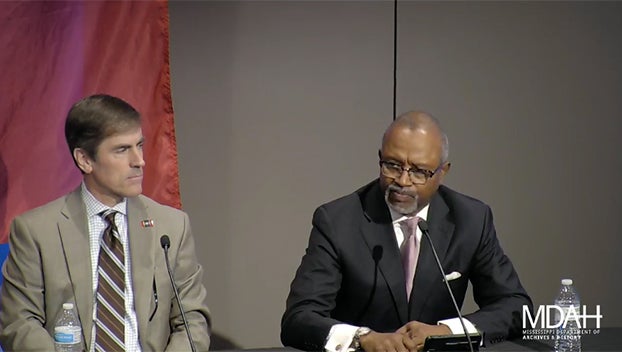

While the issue of changing it has come up many times before then, state leaders spoke out on Wednesday during the Mississippi Department of Archives and History’s weekly program, History is Lunch, regarding what generated the momentum to push legislation to retire the flag forward.

Included in this panel were Lieutenant Governor Delbert Hosemann; Speaker of the House Philip Gunn; Senator Briggs Hopson, R-Vicksburg; Senator Derrick Simmons, D-Greenville; and Representative Robert Johnson III, D-Natchez—three Republicans, two Democrats. All of them were united on one front, to change the state flag.

In his introduction, Spence Flatgard, who serves as president on MDAH’s nine-member board of trustees, said there have been moments throughout Mississippi’s history where leaders who were often divided on certain issues “step up and bring us together” so the state as a whole can move forward.

“I can think of no better example of that in recent history than this flag vote,” he said.

MDAH Director Katie Blount said Mississippi legislators “made history” when they voted 92 to 23 in the House and 37 to 14 in the Senate to pass House Bill 1796.

On July 1, 2020, the flag of the state capital was lowered and brought to the Mississippi History Museum, where it remains in an exhibit.

“Over the next few months, commissioners appointed by the governor, lieutenant governor and speaker worked in the public eye to choose a new design, the ‘In God We Trust’ flag, to appear on the ballot. On Nov. 3, Mississippi voters approved the new flag by a large margin, 72% to 28%, making headlines throughout the country and abroad,” Blount said. “The new flag carried 80 of Mississippi’s 82 counties. On Jan 6, 2021, the legislature designated the ‘In God We Trust’ flag as the new state flag. On Jan. 15, in this room, Gov. Tate Reeves signed the law and the new flag was raised above the capital. To the media and outside observers, this change seemed sudden and unexpected. But inside the capital, efforts to change the flag had been underway for years.”

To answer what propelled the issue forward in 2020, the Department of Archives and History invited state leaders to tell what happened.

Johnson said he remembers trying to force a vote on the flag issue with a lawsuit 25 years ago along with Senator David Jordan.

“There was a mood in both houses and they didn’t want to put that to a vote, but we felt that it was important—pass or fail—that it was our responsibility and we should do something.”

Johnson said another milestone came five or six years ago when Gunn and senators Thad Cochran and Roger Wicker said the flag had to go.

“When I saw all of the vitriol and all of the messages that were floating around, I remember calling Speaker Gunn and telling him, ‘Look, I know people know where you live but they don’t know where I live. … If you needed somewhere to go to get away from those threats, you can come over here.’ … It was serious. It took a lot of courage and conviction to understand what time we lived in and why it was important,” Johnson said.

State leaders said the reason the issue wouldn’t press forward for another few years is that it couldn’t without a vote of support from the House and Senate.

“We had to have 62 votes to change the flag, but we had to have 81 votes to open the door for a bill to be introduced. … Not only were we 10 votes shy of even changing the flag but we were 30 votes away from even bringing the bill out,” Gunn said.

The outlook of the legislation passing shifted “right on the heals” of May of 2020, when George Floyd’s death at the hands of police in Minneapolis, Minnesota, sparked the national Black Lives Matter movement, Gunn said.

Mississippi leaders fell under pressure to take down the confederate emblem.

Johnson said he was asked by “a group of freshman Republicans and younger Democrats” to approach Gunn with the state flag issue again.

“He said there is no point in doing that because we don’t have the votes to do it,” Johnson said. He added, “Neither of one us believed it could be done.”

During that time, Johnson said he and the Republican speaker were working together on different issues and “this was one of the most important ones.”

Johnson spoke of the message that the previous flag gave to Black Americans, telling them “don’t come” to Mississippi.

Gunn said Hopson came up and asked him what he thought of changing the flag and he realized that interest in it had been growing.

“I felt like in my heart that Mississippi could never really get to where it needed to go without changing a symbol that too many people—both in the state and outside of the state—frankly, detested or were ashamed of,” Hopson said. “… There was not a time in the legislature prior to 2020 that we felt like we could get something done.”

The leaders said Republicans who came out in favor of changing the flag had received “hate mail” from their constituents. Others faced a moral battle between voting the way they felt was right in their heart versus voting the way that could keep them in office for another term.

Gunn became emotional telling stories of how those who would face scrutiny from their districts for voting yes to change the flag still voted for it anyway.

He said the pressure for many came at them, not from the voters, but their families and their conscience.

“Your children and your grandchildren and historians are going to look at what did you do when you were given the opportunity to do something. … The vote is just going to say no. It isn’t going to say ‘voted no because—’ I didn’t want to be on the wrong side of history,” Gunn said.

Legislators were asked to vote on whether to suspend rules allowing for a vote to take place on the state flag and whether or not they would change it.

Gunn said Representative Karl Oliver, who previously denounced anyone in favor of removing confederate monuments on social media saying they “should be lynched,” told him that he would vote yes to change the flag and to suspend the rules.

“He said, ‘I’m not always going to be a legislator but will always be a father and a grandfather and I cannot have my children be embarrassed by what I do here,’” Gunn said of Oliver. “That was the moment I thought, we’ve got a chance.”

When the vote finally passed, Hosemann said it was a feeling like no other.

“The feeling we had turned a corner, that we had opened the door and allowed people to come through regardless of their race, color, creed or national origin—This was a unanimous vote that united both Republicans and Democrat. … All of those people came together and at the end, the release—I’ve never really seen anything like it. It wasn’t like a football game that you win or something. It was almost like a religious experience. We had people who had argued against each other for years hugging each other. … That has set the tone for the future. What we did was not just change a piece of cloth. We changed an opportunity.”