Cinematographers behind 15 iconic films in movie history

Published 9:00 pm Wednesday, May 18, 2022

Universum Film (UFA)

Cinematographers behind 15 iconic films in movie history

A cinematographer is vital to developing the look and feel of a successful film. Responsible for the camera and lighting crew, the choices a cinematographer makes play a critical role in how the picture turns out overall. Their work impacts everything—the look, color, lighting, and frame of every single shot in a movie, of which there can be thousands.

Therefore, it comes as no surprise that many of the most iconic films of all time were made possible by the greatest cinematographers. Many of these artists worked closely with directors to create some of the most indelible images and scenes in cinematic history.

Giggster dug into film history, chose 15 movies iconic for their cinematography, and researched the director of photography (the cinematographer) behind the project, their work on the movie, how their cinematography stands out in the film listed, and gave an example shot from the movie. The list skews heavily toward the 20th century and was guided by the American Society of Cinematographers’ list of 100 milestone films in cinematography history. IMDb user ratings and Metascores are provided for popular and critical context.

Click through for a look at these 15 iconic movies and the cinematographers who made every shot memorable.

![]()

Universum Film (UFA)

Karl Freund: ‘Metropolis’ (1927)

– Director: Fritz Lang

– IMDb user rating: 8.3

– Metascore: 98

– Runtime: 153 minutes

Karl Freund was a cinematographer who worked on over 100 films over the course of his career. He was famous for essentially taking over the filming of another well-known film, 1931’s “Dracula,” when the director left mid-shoot. “Metropolis” is not only regarded as one of the earliest examples of a science fiction film but also among the many cinematic touchstones to emerge from the German film goliath Universum Film-Aktien Gesellschaft, which was a trailblazing force of the silent film era.

Freund’s work depicting the urban landscape in “Metropolis” was heavily influenced by the futurist Italian architect Antonio Sant’Elia. In recent years, numerous filmmakers have endeavored to bring Freund’s work to life with sound and music, including that of Freddie Mercury and Loverboy.

The Archers

Jack Cardiff: ‘The Red Shoes’ (1948)

– Directors: Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger

– IMDb user rating: 8.1

– Metascore: data not available

– Runtime: 135 minutes

The cinematography for a film called “The Red Shoes” was always going to be important. After all, audiences need to feel moments of high drama and importance when the titular shoes make their appearance. The film follows the story of a ballerina consumed by her twin passions for dance and desire for love.

Cardiff’s work masterfully renders the flashes of red shoes across the screen as symbols of both desires. He used something called a three-strip process to bring the film’s colors to the forefront of a viewer’s consciousness. This required extreme levels of skill and was tremendously expensive, but the end result left audiences dazzled.

United Artists/Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

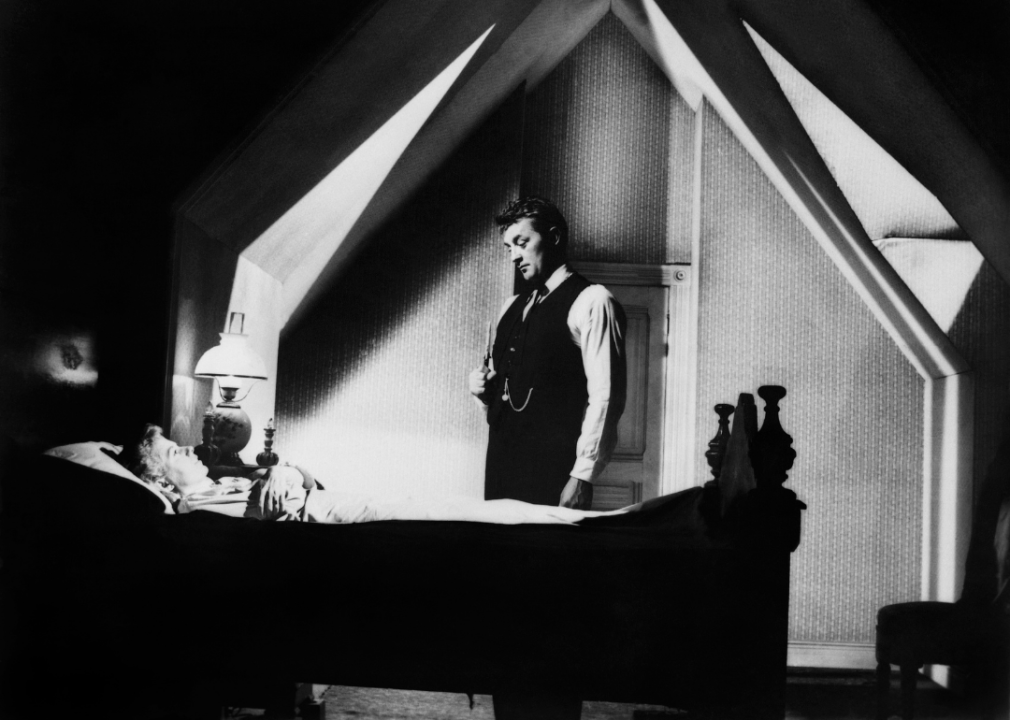

Stanley Cortez: ‘The Night of the Hunter’ (1955)

– Director: Charles Laughton

– IMDb user rating: 8.0

– Metascore: 99

– Runtime: 92 minutes

“The Night of the Hunter” is widely considered one of the most visually arresting movies ever made. Stanley Cortez worked in extremely close and intimate detail with all the other major players in the film. He had long philosophical conversations with the movie’s director and writer and helped ensure the entire film was shot in 36 days. Cortez created eerie sets, full of shadowy buildings and distant hillscapes, along with a pond that plays a pivotal role in the story.

Horizon Pictures

Freddie Young: ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ (1962)

– Director: David Lean

– IMDb user rating: 8.3

– Metascore: 100

– Runtime: 218 minutes

“Lawrence of Arabia” takes place almost entirely in the desert. Freddie Young was almost 60 when he worked on the film and had been thinking about making a similar movie since the 1920s. Perhaps the scene for which he’s best remembered is the one with Omar Sharif emerging from a desert mirage. Young made the shot possible with a telephoto lens. He’d brought it to film from Panavision in the United States for just such an occasion.

Metor-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM)

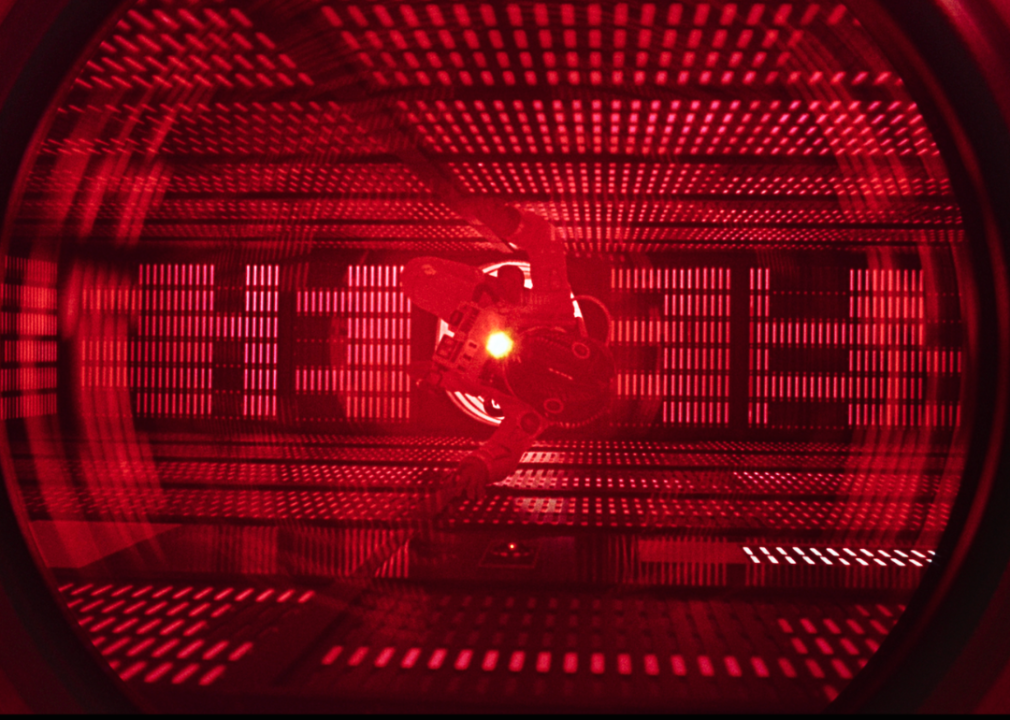

Geoffrey Unsworth: ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (1968)

– Director: Stanley Kubrick

– IMDb user rating: 8.3

– Metascore: 84

– Runtime: 149 minutes

“2001: A Space Odyssey” is another science fiction film set in the future. Geoffrey Unsworth used a number of unusual techniques to achieve the movie’s futuristic look, among them being the use of strip lights in the walls of the film’s centrifuge. It was difficult for the cameramen to get shots inside the centrifuge that didn’t expose some of the hidden lights and the lenses had to be set to wide-angle nearly all the time. This meticulous coordination of lighting, camerawork, and set design is just one of many creative and logistical solutions Unsworth came up with when looking to set a film in what was then an unimaginable future.

Paramount Pictures

Gordon Willis: ‘The Godfather’ (1972)

– Director: Francis Ford Coppola

– IMDb user rating: 9.2

– Metascore: 100

– Runtime: 175 minutes

“The Godfather” is easily one of the most iconic films ever made. Gordon Willis’ work on the film is widely considered to have influenced almost every cinematographer who came after him. Willis used techniques such as placing actors intentionally in darkness to simultaneously solve lighting issues and do character work. He used a single top light in similar ways. When they beamed down on Marlon Brando, they did the double work of not only illuminating him, but also conferring a gravitas upon Brando essential to his character and the plot.

Paramount Pictures

Néstor Almendros: ‘Days of Heaven’ (1978)

– Director: Terrence Malick

– IMDb user rating: 7.8

– Metascore: 93

– Runtime: 94 minutes

Néstor Almendros won the Academy Award for his work in 1978’s “Days of Heaven.” The film is set in 1916 among the oilfields of rural Texas. It is heavily atmospheric and features stark and stunning shots of the Texan landscape, combined with dramatically contrasting lighting. Almendros’ achievement is all the more stunning for the fact that he worked on the film while he was losing his own vision. No one would have ever been able to tell on set and it wasn’t until a later interview when the film’s star, Richard Gere, let it slip that Almendros had worked on the film nearly blind.

American Zoetrope

Vittorio Storaro: ‘Apocalypse Now’ (1979)

– Director: Francis Ford Coppola

– IMDb user rating: 8.5

– Metascore: 94

– Runtime: 147 minutes

From the opening shots of “Apocalypse Now,” set on the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, no one who has ever seen the film will be able to forget its stunning visuals—and Vittorio Storaro certainly had his work cut out for him making the film. Storaro intentionally used colors and light in contrast to the darkness of the jungle while filming in the Philippines. He worked closely with famed director Francis Ford Coppola and has said that one of his preeminent memories from making the film was arriving to find Coppola’s sketches of a helicopter attack scene, and wondering if he’d be able to pull off the effect Coppola wanted. Needless to say, he delivered, and was rewarded with an Academy Award.

The Ladd Company

Jordan Cronenweth: ‘Blade Runner’ (1982)

– Director: Ridley Scott

– IMDb user rating: 8.1

– Metascore: 84

– Runtime: 117 minutes

“Blade Runner” is famous for its use of light and shadow. Much of that was the work of cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth. Director Ridley Scott wanted the movie’s feeling to evoke the film noir of the 1940s and ’50s. Cronenweth achieved that effect by using strong shafts of light along with backlighting. He also used high-contrast and unusual camera angles in order to deliver a look and feel similar to another template Scott laid out—that of the film “Citizen Kane.”

Road Movies Filmproduktion

Robby Müller: ‘Paris, Texas’ (1984)

– Director: Wim Wenders

– IMDb user rating: 8.0

– Metascore: 78

– Runtime: 145 minutes

Robby Müller has been called the “master of light”—and after one viewing of his work on “Paris, Texas,” it’s not hard to see why. The film centers on characters in extreme emotional states, and Müller’s expert use of light manages to mirror those states. Set in the harsh, hot plains of Texas, Müller’s light has been called almost impossibly real-looking, as opposed to the typical film set lighting, and contrasts palpably with the darkness many of the characters are grappling with inside.

Warner Bros.

Robert Richardson: ‘JFK’ (1991)

– Director: Oliver Stone

– IMDb user rating: 8.0

– Metascore: 72

– Runtime: 189 minutes

Cinematography is at the heart of the plot in “JFK.” After all, the film centers around footage from the Nov. 22, 1963, assassination of U.S President John F. Kennedy. Richardson riffs on the style of the famous Zapruder film—real footage shot by a private citizen—of the moment Kennedy was shot in Dallas. His work for the film is an unusual blend of fact and fiction, much like the plot of the film itself. The picture takes an authentic tragedy and builds a fictional world around it. Richardson mirrors that tendency with his own work, mixing real and manufactured images together to create an immersive whole.

Dreamworks Pictures

Janusz Kamiński: ‘Saving Private Ryan’ (1998)

– Director: Steven Spielberg

– IMDb user rating: 8.6

– Metascore: 91

– Runtime: 169 minutes

With its graphic scenes of combat on the battlefields of World War II, “Saving Private Ryan” is a visually arresting movie. Cinematographer Janusz Kamiński attributes much of this powerful work to his relative youth when he worked on the film. Being young, he has said, enabled him to experiment with different photographic and lab techniques.

“Youth has a lot of attributes, and one of them is that you take chances,” said Kamiński. “Certainly, from a visual standpoint, we took chances on that film.” Some of the most memorable scenes include the unforgettable opening montage, in which the camera takes the point of view of Allied troops wading ashore at Omaha Beach, suffering high casualties from enemy fire.

Block 2 Pictures

Christopher Doyle: ‘In the Mood for Love’ (2000)

– Director: Wong Kar-wai

– IMDb user rating: 8.0

– Metascore: 85

– Runtime: 98 minutes

“In the Mood for Love” has been influential since its release, with a number of bars and fashion brands named after it and filmmakers citing it as inspiration. Christopher Doyle’s cinematography is one reason why. Doyle used many techniques and effects to evoke the mood of the film suggested by the title. He used not only bright, primary colors but also cigarette smoke. He even worked with the costume department to make the stars’ wardrobes pop alongside all the other visuals he placed in his lens, creating an atmosphere that continues to inspire today.

Paramount Vantage

Roger Deakins: ‘No Country for Old Men’ (2007)

– Directors: Ethan Coen, Joel Coen

– IMDb user rating: 8.2

– Metascore: 92

– Runtime: 122 minutes

A crime story set in Texas at its core, “No Country for Old Men” is full of foreboding visuals. Roger Deakins was responsible for creating that atmosphere, along with revamping the feel of contemporary Westerns. Deakins worked with the directors to achieve this feel by shooting on film with an Arriflex 535B. The film’s stock was also shot with a Kodak Vision 2383 using 35 mm. That old-time atmosphere was conjured not just by a good eye, but also by Deakins’ commitment to using the same tools that would have been used during the time in which the film was set.

Warner Bros.

Emmanuel Lubezki: ‘Gravity’ (2013)

– Director: Alfonso Cuarón

– IMDb user rating: 7.7

– Metascore: 96

– Runtime: 91 minutes

Emmanuel Lubezki faced a unique challenge working on “Gravity.” Much of the film takes place in outer space, which comes with different lighting conditions than those on Earth. Lubezki’s initial task was to come up with lighting for the film’s opening shot of Earth, as viewed from a space shuttle. Lubezki has said that he considered the work of Vittorio Storaro, in particular, when thinking of how to use lighting to achieve the desired mood. “The light is friendly in the beginning of the movie,” said Lubezki. “And during that shot it becomes more complex and more threatening and more dynamic.”

This story originally appeared on Giggster

and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.