American bison are making a major comeback

Published 1:47 pm Monday, July 11, 2022

Darren Baker // Shutterstock

American bison are making a major comeback

The Fish and Wildlife Service in early June announced that several petitions to add Yellowstone bison to the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 presented “substantial” arguments that ESA protections “may be warranted.”

It wasn’t too long ago—roughly 150 years—that nearly 30 million American bison (Bison bison) lived throughout the Great Plains between the Rocky Mountains in the West and the Appalachian Mountains in the East. But with white settler populations exploding throughout the region in the late 19th century, hunters severely diminished the bison population by killing around 5,000 of the animals every day in 1871 and 1872. At the same time, bison habitat rapidly eroded as farmland, cities, and fenced-off pasture for cattle were established in the shadows of bison territory. Novel diseases took care of the rest.

By 1889, free-ranging bison numbers dwindled to almost zero. This reduction of more than 99.9% of the population ushered in a century of bison-less Great Plains. Natural habitat, grassland, other animal populations, and Indigenous communities all suffered.

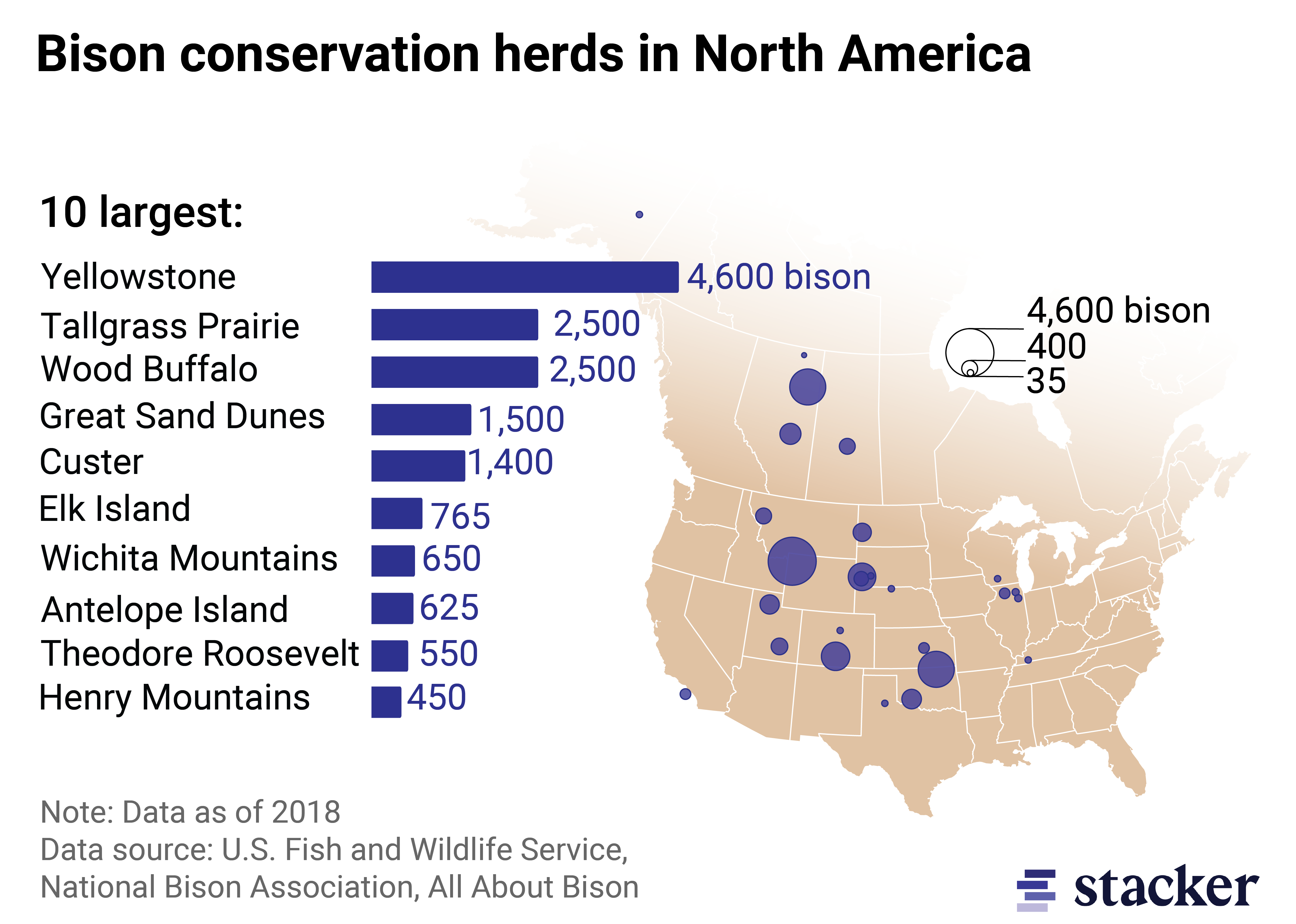

A modest collection of federally managed herds in the early 20th century brought bison back from the brink. With approximately 11,000 Plains bison in 19 herds, the Department of the Interior is today’s lead conservation steward for North American Plains bison across 4.6 million acres of National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Land Management lands in 12 states.

Conservation efforts, responsible farming, and an ambitious relocation effort have afforded a bison population boom in recent years. While small and isolated, populations are ascending with roughly 350,000 Plains bison in production herds, 30,000 in public herds, and around 20,000 in tribal herds.

To learn more about the ultimate American comeback story, Stacker explored the history of bison populations in the U.S. and repopulation efforts underway.

You may also like: What 60 years of data tell us about our garbage habits

![]()

Emma Rubin // Stacker

Yellowstone represents the largest conservation herd of buffalo in the US

Yellowstone bison present the purest bloodline to native Plains bison that lived in North America prior to European settlers who crossbred the bison with cattle. These animals can reach a staggering 2,000 pounds, live for more than 20 years, and provide an essential link in the habitat and ecosystem of the Great Plains.

“Meaningful things are happening in animal conservation, particularly with Yellowstone bison,” Chamois Anderson, the senior Rockies and Plains representative at Defenders of Wildlife, told Stacker in an interview. Anderson’s work includes collaborations with conservation partners and state and federal agencies, and education and outreach.

Defenders of Wildlife supports the National Parks Service’s Bison Conservation Transfer Program in cooperation with the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of Fort Peck to return bison to tribal lands.

Anh Luu // Shutterstock

Bison are critical to the ecosystems they sprang from and the cultural fabric of Indigenous populations

Bison are critical not just to the Great Plains ecosystem, but, equally important, to the cultural and spiritual lives of Native Americans.

“These animals are extremely important to our grasslands,” Anderson said. “They are an ecological engineer. They have the ability to graze in a mosaic pattern, clipping them down just enough so they grow back succulent and nutritious for a number of species.”

Bison have symbiotic relationships with grasses and animals alike. The black-tailed prairie dog, for one, attracts bison with piles of dirt the dogs dig in creating their burrows. Bison fertilize the soil around the tunnels and eat tall grass, allowing shorter, nutritious grass to grow and feed the prairie dogs.

Indigenous tribal communities represent a cultural connection to bison. The Buffalo Treaty of 2014 represents the first, formal acknowledgment of the importance of bison to Native Americans and First Nations peoples. In ratifying the treaty, 13 nations from eight reservations formed an intertribal alliance committed to the reintroduction of wild bison across North America. President Barack Obama in 2016 took another step in signing legislation that officially named bison the first national mammal of the United States.

Geoffrey Kuchera // Shutterstock

The bison’s decimation is due to a constellation of factors—and repopulation efforts are complex

Not long after white settlers arrived in the eventual United States, bison hunters overexploited the species’ population for meat, hides, and other products.

In addition to hunting, development created a big problem for bison—from railroads to towns and industry. “We have to acknowledge that what we did to the Plains Indians was to take out their food source,” Anderson said.

“Many of my friends and partners say, ‘This [bison] was our family.’ We pushed them onto reservations and destroyed the buffalo. We did a number on the species, so much so that we only had about 1,000 left.”

Many estimates are much lower, with a National Bureau of Economic Research paper suggesting there may have been fewer than 100 bison at one point.

As numbers increase within national parks, conservation projects and organizations have undertaken relocation efforts. But this work requires creativity, as grazing animals of this size need significant space to roam.

Complicating repopulation efforts is the fact that bison can be carriers for brucellosis, a disease that easily passes to livestock and causes abortions and stillbirths in those animals affected. Because of the potential for devastating effects of brucellosis on the agriculture industry, much effort has been put into ensuring bison—particularly animals carrying brucellosis—do not intermingle with cattle.

While the transmission is largely the result of contact with matter leftover from a bison birth, federal officials have claimed males may also carry brucellosis. Methods of testing for brucellosis are hardly foolproof. Testing is tricky and often faulty—between 1996 and 1999, 80% of all bison that field-tested positive for brucellosis and were killed tested negative in subsequent lab tests.

Bison repopulation is also highly political, stymied by a limited natural resource: grass.

Like wild bison, the agriculture industry depends on having massive spaces for growing food and for cattle farming. As bison numbers swelled through mid-20th-century conservation efforts, animals that wandered outside park property lines were met with scars of highways etched across the countryside, housing developments, and mile after mile of paddocks for domesticated grazing animals.

“We can do this together,” Anderson said, adding that restoring bison herds doesn’t necessitate tearing down farm fencing. “Cattle ranching is important out west,” Anderson said. “We can do both.”

One of the most ambitious repopulation efforts to date is The Bison Conservation Transfer Program, launched in 2019 by the NPS to identify bison that don’t have brucellosis and transfer them to new areas as an alternative to sending them to slaughter. Since 2019, 182 bison have been successfully transferred to the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation.

Tribal lands offer the space these animals desperately need and a culture that has respected bison since the beginning. “The transfer program is all about diverting animals from slaughter,” Anderson said, sending them to Fort Peck for quarantine, then we partner with the Intertribal Buffalo Council. Their mission is to take genetically viable herds and bring them to tribal lands as cultural herds.”

Inger Eriksen // Shutterstock

The transfer program takes a long time—and a lot of testing

The transfer of bison is a yearslong process for each animal.

If a bison captured for transfer tests negative for brucellosis, Anderson explained, it goes to quarantine. “Part of the protocol is that the female has to have at least one baby [in quarantine],” Anderson said, “and that animal has to be tested. Males can’t spread this, but they are still scrutinized. Meanwhile, quarantine is two and a half years, on average.” Animals that test positive are sent to slaughter (the disease does not affect the meat) and utilized by the tribe that would have received the transferred animal.

Bison that pass quarantine are transported in large groups by truck. “There’s an 800,000-acre facility at Fort Peck. Animals show up and are released into a large pasture on the prairie in divided pens with additional testing.” After the last test, it’s time for transport.

“The bison are in these big pastures on the edge of Yellowstone,” Anderson said, “foraging on native grasses. They run them through a shoot and do the blood test, and then at that point, they’ll [oftentimes] microchip. We partner with the Smithsonian on that. Then we get the truck there. It’s not like moving cows or cattle—you can’t just throw a bunch of bulls in the back and hit the road. You have to separate the bulls. We’ll often put the cows with the calves.

“Then they drive 600 miles from Yellowstone to Fort Peck in one stretch. We hire a veterinarian to be part of the state transportation plan in case something happens. We get them there, usually in the middle of the night, and we want to make sure to unload them so the moms can find their babies and the babies can find their moms. Sometimes the bulls get stubborn—we have to put hay out to lure them. They get to their final destination a year later.”

Last December, 56 bison were relocated to tribal lands in Washington and Oklahoma, with the Yakama Nation and Modoc Nation each receiving entirely intact families of bison: 28 to each nation of cows, bulls, and yearlings. “That’s really good because you want to give diversity of ages, genders, and so forth,” Anderson said.

“These wild herds get started on a dedicated landscape. Once they hit that prairie, they are wild.”

YegoroV // Shutterstock

The goal: A ‘metapopulation’

The Bison Conservation Transfer Program seeks to transfer 175 bison by the end of the summer in 2022—a significant jump from the 192 transferred over the last three years. The goal is to ultimately have a metapopulation whereby smaller herds add up to a wild bison population stretching from Canada to Mexico.

“We’re not going to have this giant connected land for bison—there will still be space for cattle grazing, but on a site-by-site basis,” Anderson said. “We’re never going to see 30 million … but we’ve got to move the needle.”

You may also like: How far is the US from a 100% renewable energy future?