Hitchcock vs. Spielberg: how the legendary directors stack up

Published 1:02 pm Thursday, August 4, 2022

AFP // Getty Images

Hitchcock vs. Spielberg: how the legendary directors stack up

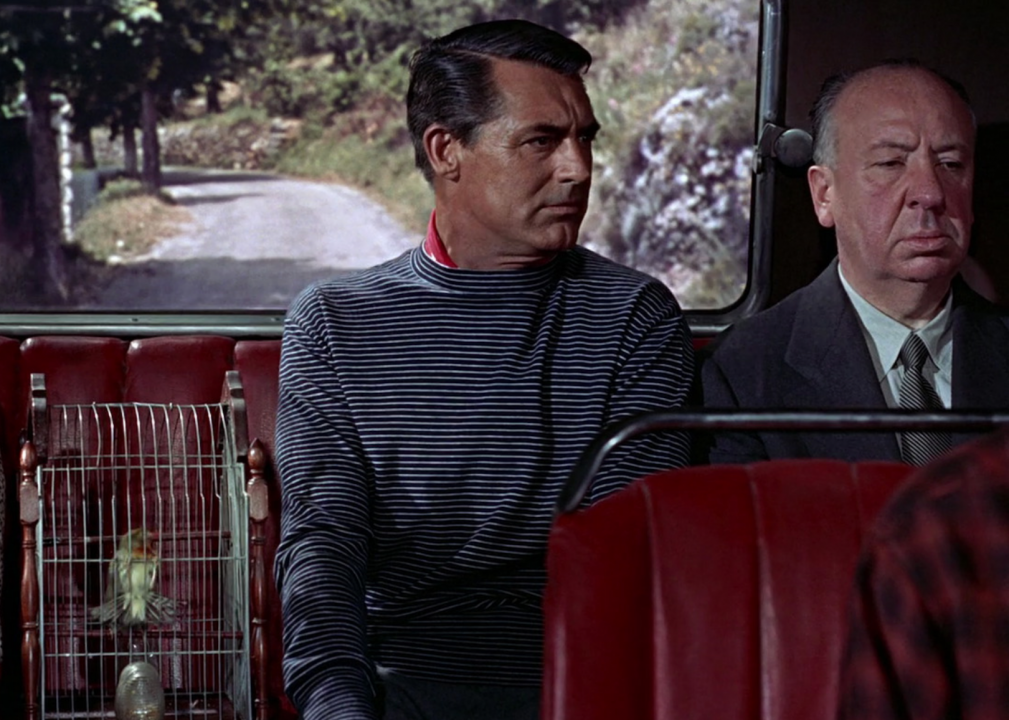

Only an artist as great as Master of Suspense Alfred Hitchcock can get away with a line like “Self-plagiarism is style.” Hitchcock’s famous words are in reference to his highly stylized and perennially influential brand of macabre cinema—the very brand that turned him into the filmmaking idol of a young Steven Spielberg. Despite only ever recognizing Spielberg as the “the boy who made the fish movie,” Hitchcock’s influence would be enough to spark Spielberg into a flame of eventual eminence. Today, the two are recognized as some of the most significant filmmakers of all time—and rightfully so.

In order to compare and contrast Hitchcock and Spielberg from 24 different angles, Stacker collected data and information from a wide array of source materials that include first films, audience favorites, shot lengths, box office numbers, career spans, genres, and cameos (among many other aspects of their careers). Ultimately, Hitchcock and Spielberg shine in every category assessed; but their work aligns and differs in various ways from average runtimes to creative droughts.

Almost a millennium of widely renowned filmmaking between the two makes for a range and depth of analysis as fascinating to collate as it is gratifying to consider. Crack open the treasure chest of nostalgia flooded with the likes of that fish movie “Jaws,” “North by Northwest,” “Jurassic Park,” “Vertigo,” Indiana Jones, and Norman Bates, with two filmmakers whose portfolios are as rich as they are recognizable. Hitchcock and Spielberg’s unimpeachable stature in the medium and the wistful memories their films invoke will leave you thirsty for a classic. The hardest part will be deciding in which to indulge.

You may also like: 100 greatest foreign-language films of all time

![]()

Peter Dunne/Express // Getty Images

Early life

Born in London on Aug. 13, 1899, Hitchcock preceded Spielberg (born Dec. 18, 1946, in Cincinnati, Ohio) by 47 years—a fact that distances the two more significantly than any aspect of their filmmaking legacies. Hitchcock and his two siblings were raised by stern British parents near Jack the Ripper’s old stomping grounds on the East End.

Spielberg and his three sisters were raised by a concert pianist for a mother and electrical engineer for a father, whose ever-changing career in computers kept the Spielberg family on the move until they settled in Silicon Valley (pre-moniker).

Getty Images

Education

Hitchcock enrolled in a few different educational programs before breaking into the world of film. Most notably, he attended the London County Council School of Marine Engineering and Navigation from 1913 to 1914 and studied drawing and design at the University of London in 1916 before going on to write title cards for silent films.

Spielberg was rejected from the USC School of Cinematic Arts and eventually settled on California State University at Long Beach. He dropped out when Universal Studios offered him a contract for $300 a week. In 2002, after over three decades of overwhelming success, Spielberg went back to finish his bachelor of arts at Cal State.

Universal Pictures

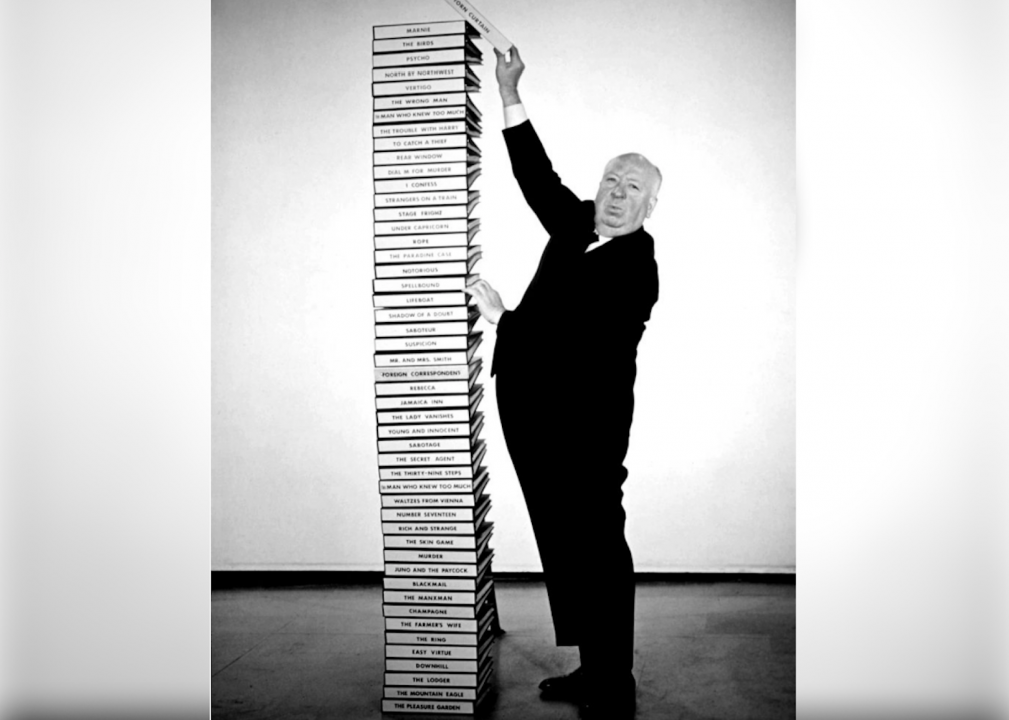

Career span

Hitchcock began his filmmaking career in 1920 with American studio Famous Players-Lasky. He wouldn’t try his hand at directing for a couple more years. In 1976, he directed his final film, “Family Plot,” a Barbara Harris and Bruce Dern vehicle. He died in Los Angeles four years later.

Spielberg made films before he was ever paid to, but his professional career began after MCA/Universal executive Sidney Sheinberg saw his short film “Amblin'” (1968) and offered him a TV contract. Of course, Spielberg is still alive and going strong at 72 with three high-profile films slated for arrival between now and 2021.

Universal Television

Consistency

From “Duel” (1971) to “Ready Player One” (2018), Spielberg has directed 35 feature films in 48 years. That averages out to 1.37 years, or 500 days, between each.

Hitchcock made 54 feature films in 52 years, from “The Pleasure Garden” (1925) to “Family Plot” (1976), resulting in 1.04 years, or 379 days, on average between each film. For your typical great director in the 21st century, those are furious rates of production. Spielberg is still relatively singular in how often he directs films. But in Hitchcock’s time, that rate of filmmaking was typical. All-timers like John Ford, Akira Kurosawa, Howard Hawks, and Yasujiro Ozu cranked movies out just as, if not more, frequently.

American Artist Productions

First films

Hitchcock’s first film came after a mini-career’s worth of holding other jobs on film sets, including that of production designer and assistant director. The comedy was called “Mrs. Peabody” or “Number 13,” depending on who you talk to. Unfortunately, the film was never finished due to lack of finances. He wouldn’t complete his first feature until 1925 with “The Pleasure Garden,” and wouldn’t gain notoriety until the release of his 1927 project, “The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog.”

Little Spielberg was as passionate about filmmaking as the Spielberg audiences know now. As a child, he filmed family vacations with an 8mm camera, eventually graduating to his first narrative project “Escape to Nowhere” (1962), a medium-length war movie. His first full-length feature, “Firelight” (1964), was a $400 sci-fi picture that had one local theatrical screening per his parents’ financial support. 1974 saw the release of his first nationally distributed theatrical film “The Sugarland Express,” which would pale in comparison to 1975’s industry-busting “Jaws.”

Zanuck // Brown Productions

As director

IMDb credits Spielberg with 58 directorial gigs overall. Thirty-one of those are theatrically distributed feature fiction films; 10 are for multiple episodes of TV or segments of a mini-series; eight are shorts, both fiction and nonfiction; three are TV movies; and three are feature films slated for release in the near future. One is a video game, another a segment of “Twilight Zone: The Movie,” and another his anomalistic “Firelight,” which doesn’t neatly fit into the other categories.

Hitchcock is credited for 70 directorial projects, including 54 theatrically distributed feature films. The other 16 are comprised of eight shorts, five TV shows, one nonfiction TV movie, one unfinished feature, and one credit for “some sketches” in “Elstree Calling” (1930).

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

As producer

The auteur theory holds that the director is the ultimate creative force, or artist, of the film. Auteurs are uncommon these days. Your average studio movie is the product of directors, screenwriters, and producers alike sharing the weight of final decisions. But Hitchcock was a perfectionist, the classic epitome of an auteur—perhaps an over-aggressive version of one, like Stanley Kubrick—running sets like a totalitarian regime and deflecting all creative debate. He was only technically credited as producer for one feature film, “Lord Camber’s Ladies,” a forgotten Benn W. Levy picture, but he was as much a producer as he was a director. He did, however, get official producer/executive producer credits on a few TV series.

Spielberg, on the other hand, is almost as recognized for his production credits as he is for his director credits. He’s produced nearly all of his own films along with celebrated greats like “Poltergeist” (1982), “Letters from Iwo Jima” (2006), and “Super 8” (2011). Overall, he has 173 production credits to his name, most of which are executive producer credits that mean he supported the film financially under the banner of his two production companies, Amblin Entertainment and DreamWorks Pictures.

Warner Brothers // Dreamworks

As writer

Spielberg started off writing his own screenplays, but shifted early in his career to picking out screenplays from writers he trusted or recruiting writers he could creatively supervise for a story he wanted to tell. A bulk of his writing credits are for the groundbreaking “Medal of Honor” video game series, which he created in 1999. However, of the 22 writing credits to his name, only four of them are penned screenplays, the last being “A.I. Artificial Intelligence” (2001)—the writing of which was born out of a commitment he’d made to Kubrick long before he died. The others are mostly comprised of creator, developer, or story by credits.

Hitchcock worked in a similar vein. He wrote much more at the beginning of his career—primarily adaptations—and racked up more screenwriting credits than Spielberg, but left the pen in the dust once he took off as a director-producer. His last full screenwriting credit was of the adaptation for 1931’s “East of Shanghai.”

Paramount Pictures

As actor

Hitchcock was well-known for his cameos in his own films. He made 39 in total, only one standing out as a cameo in a live TV series called “Lux Video Theatre,” but he never acted in a film outside of his cameos.

Spielberg’s 15 acting credits coagulate into a trail of instances of Spielberg having cameo fun with his high-profile friends. He played an office clerk in “The Blues Brothers” (1980), an alien in “Men in Black” (1997), and has shown up as himself more often than not. He and director pal Cameron Crowe decided to exchange cameos in their back-to-back Tom Cruise features. Spielberg was a guest at a party in “Vanilla Sky” (2001) and Crowe was a man on a train in “Minority Report” (2002).

Warner Brothers // Amblin Entertainment

As other

Both directors have stuck to their director-producer roles quite tightly, but they did have their moments out of the spotlight. Hitchcock designed titles for 12 silent films from 1920 to 1922, served as art director on nine films from 1922–1925, and assistant directed on five films from 1923 to 1925.

Spielberg’s other credits are, like his acting credits, much more frivolous. He played the clarinet in the famous “Jaws” (1975) theme and was an uncredited second unit director for “The Haunting” (1999), “Arachnophobia” (1990), Amblin’ Entertainment’s “The Goonies” (1985), and best buddy George Lucas’s “Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith” (2005).

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM)

Genre

Hitchcock once said, “I’m a typed director. If I made ‘Cinderella,’ the audience would immediately be looking for a body in the coach.” In other words, Hitchcock stuck primarily to one genre, although it’s worth recognizing that “genre” can be a limiting concept if relied on too heavily. There were always distinctions in Hitchcock’s work. Most of his films could best be described as “thrillers” or “suspense” films that came in the form of espionage, slashers, romance, film noir, horror, and other variations. Yet he did not merely make thrillers. Hitchcock is commonly credited with inventing them and several of their subgenres, like modern horror, hence his nickname “Master of Suspense.”

Spielberg is impressive and influential in a different sense. Like Stanley Kubrick, he’s conquered several genres, finding ways to attribute his mastery to completely new film expressions. He’s made sci-fi films (“Minority Report”), historical dramas (“Schindler’s List”), horror-thrillers (“Jaws”), slightly romantic comedies (“The Terminal”), adventure films (Indiana Jones), kids films (“E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial”), war films (“Saving Private Ryan”), and more.

LEON NEAL/AFP // Getty Images

Shot length

Average shot length (ASL) is not a popularly discussed aspect of a film, but it says a lot about the directors and/or producers in charge. Take Michael Bay and Paul Thomas Anderson, for example. Bay’s chaotic action blockbusters hold an ASL of 3 seconds, while P.T. Anderson’s calculated, lingering auteur dramas hold an ASL of 13.4 seconds.

Hitchcock’s 9.1 second ASL reflects an era of much more patient popular filmmaking, while Spielberg’s 6.5 second ASL echoes the birth and concomitant development of the blockbuster genre as a more spastic iteration of the medium, eventually leading to extremes like Michael Bay.

Shamley Productions

Runtime

Runtime is one of the most divisive aspects between Hitchcock and Spielberg films. Hitchcock’s average feature is an hour and 40 minutes long, while Spielberg’s average feature is two hours and 10 minutes long—a drastic difference that reflects the trends of each director’s time period as significantly as it reflects their dedication to certain ethics of filmmaking.

Hitchcock is quoted as saying that the “length of a film should be directly related to the endurance of the human bladder,” and he wasn’t kidding. He only made eight films over two hours, and never made a film longer than two hours and 23 minutes (“Topaz”). Spielberg has only made 12 films under two hours, and his longest is a whopping three hours and 15 minutes long (“Schindler’s List”).

Universal Pictures

Droughts

Nearly every artist—even the lauded greats—hits a dry spell. Hitchcock and Spielberg are no exceptions. Hitchcock’s most apparent droughts bookend his career. From 1928–1932, he directed 11 films; only one of which has an IMDb user score above 6.4/10. From 1966 to 1969, he only directed two films (“Topaz,” “Frenzy”), both of which have since garnered worse IMDb user scores than any movie he made in the 18 years prior.

Spielberg’s droughts have been less pronounced. 1978 to 1980 only resulted in one Spielberg film called “1941” (1979), by far Spielberg’s most critically and popularly lambasted movie. But it came in between two all-time Spielberg classics in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (1977) and “Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark” (1981). Likewise, 1989 through 1991 saw the releases of “Always” and “Hook,” critical and popular bottom-dwellers of the Spielberg filmography, however more well-liked than most directors’ worsts.

Dreamworks

Streaks

Not every director catches stride quite like Hitchcock or Spielberg. Their streaks are among many aspects setting them leagues apart from their contemporaries, who could only ever dream of such swimming successes. The years between 1950 through 1964 represent what was essentially one long streak for Hitchcock, with none of his 14 films registering below a 7.1 on IMDb. And if we zoom in on 1958 through 1963, we see what might be one of the most impressive streaks of all-time in “Vertigo,” “North by Northwest,” “Psycho,” and “The Birds” back-to-back-to-back-to-back.

Spielberg’s career is mainly one unbelievable streak of a directorial span with the occasional dud peppered in. He has several mind-blowing back-to-backs, such as “Jaws” and “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” in 1975 and 1977, “Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark” and “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial” in 1981 and 1982, and “Jurassic Park” and “Schindler’s List” both in 1993. But his most uninterrupted streak runs from 1998 to 2002 with “Saving Private Ryan,” “A.I. Artificial Intelligence,” “Minority Report,” and “Catch Me If You Can.”

Paramount Pictures

Best of the box office

Adjusted for inflation, Hitchcock’s best performing films at the box office were “Rear Window” at $452.3 million coming in at #2 in 1954, “Psycho” at $382.2 million coming in at #3 in 1960, and “Notorious” at $335.9 million coming in at #8 in 1946. While no one really compares to Spielberg in box office success, Hitchcock was always a name that drove the masses to the silver screen. Only 10 of his films made less than $100 million.

Spielberg is the only director to ever break the $10 billion ceiling of box office revenue, and that’s only considering the films he’s directed. Adjusted for inflation, his top-grossing films are “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial” (1982) at $1.28 billion, “Jaws” (1975) at $1.16 billion, and “Jurassic Park” (1993) at $828 million, all three landing #1 spots in their respective years. “Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark” came in at #1, as well, raking in $800 million in 1981.

DreamWorks

Worst of the box office

Spielberg’s worst box office performers are three of his less appealing and critically adored movies, making obvious picks for last place. His worst was his first widely distributed film, “The Sugarland Express” (1974), at $36.2 million, followed by “Empire of the Sun” (1987) at $49.8 million, and relative flop “The BFG” (2016) at $58.9 million.

Hitchcock’s most disappointing box office performers came surprisingly near the heart of his career. “Stage Fright” (1950) earned the least at $54 million, followed by “The Wrong Man” (1956) at $54.3 million, and “The Trouble with Harry” (1955) at $64.1 million. The films boasted stars like Marlene Dietrich, Henry Fonda, and Shirley MacLaine in a time when star power was the lion’s share of a movie’s draw, but bombed nevertheless.

Universal Pictures

Audience reactions

Audiences have adored Spielberg and Hitchcock alike for decades—and the data shows it. The average IMDb user score for a Hitchcock feature film is 7.0, the lowest being a terribly rare 4.9 (“Juno and the Paycock”) and the highest clocking in at a universally adoring 8.5.

Spielberg’s popular appeal is a little better in all facets, although it’s worth noting that he benefits in immeasurable ways from aligning with the era of technological advancement that brought IMDb user scores to begin with. The average Spielberg feature films gets a 7.3, the lowest a 5.5—unsurprisingly an early TV movie called “Something Evil”—and the highest a stellar 8.9.

Shamley Productions

Audience favorites

Hitchcock’s five films most beloved by audiences are “Psycho” (8.5—532,761 votes), “Rear Window” (8.5—395,458 votes), “Vertigo” (8.3—317,557 votes), “North by Northwest” (8.3—269,568 votes), and “Dial M for Murder” (8.2—139,682 votes).

Spielberg’s top five films according to audiences are “Schindler’s List” (8.9—1,078,145 votes), “Saving Private Ryan” (8.6—1,100,059 votes), “Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark” (8.5—805,524 votes), “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” (8.2—628,925 votes), and “Jurassic Park” (8.1—777,389 votes). All 10 films rank at or above #181 in the top 250 on IMDb, with “Schindler’s List” topping out at #6 of all time and “Psycho” landing at #33 of all time.

Universal Pictures/Amblin Entertainment

Critic reactions

Measuring critical response is a messy business without any hard or fast lines for defining praise or scorn. It’s also a weak measure of directors’ critical acclaim across time, as the dramatic peak in film criticism during Spielberg’s days makes it much easier to lock down a critical consensus on his films. Companies like Metacritic have made the most comprehensive effort to translate critics’ reviews into data, but have yet to compile enough reviews for 39 of Hitchcock’s films to offer a reasonable consensus score. Compare that to only six Spielberg movies without a score, and the benefit of Spielberg’s modernity is glaring.

Famed first critics Andre Bazin and Andrew Sarris consistently gave Hitchcock’s films the highest marks, and Roger Ebert extolled them retrospectively. He gained significant overseas notoriety from French Cahiers du Cinema critics-turned-filmmakers like Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard. Pauline Kael was one of his only noteworthy critical dissenters on a regular basis. She thought his later, most successful work lacked creativity, and accused him of being “quite rigid, almost like a religious fanatic.” Spielberg has long been adored, as well, only one of his 29 films listed as “generally unfavorable” and eight of the 29 recognized by their “universal acclaim,” the site’s highest category of acclamation.

Alfred J. Hitchcock Productions

Critic favorites

Hitchcock’s most extensively covered and most revered films are “North by Northwest” (1959) with a Metascore of 98/100, “Psycho” (1960) with a Metascore of 97, and “Shadow of a Doubt” (1943) with a Metascore of 94. However, it should be noted that critically adored movies like “Rebecca” (1940), “Vertigo” (1958), and “Rear Window” (1954) do not have registered scores. In 2012, a comprehensive survey conducted by Sight & Sound named “Vertigo” the best film of all time. MovieMaker Magazine in 2002 named Hitchcock the most influential director of all time.

Spielberg’s most critically adored films are “Schindler’s List” (1993) with a Metascore of 93, “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial” (1982) with a Metascore of 91, and “Saving Private Ryan” (1998) with a Metascore of 91. In an infrequent bout of solidarity, critics and audiences align quite nicely.

DreamWorks

Recurring actors

Clare Greet tops the list of actors who have worked with Hitchcock the most. She was in seven of his films between 1922 and 1939. Next most is Leo G. Carroll, who began working with Hitchcock right when Greet stopped. He was in six of Hitchcock’s films from 1940 to 1959. Cary Grant and James Stewart tie for third with four films each, although they’re likely to be the most recognizable frequent collaborators due to their lead roles in some of his most famous films (“Rear Window” and “Vertigo” for Stewart, and “Notorious” and “North by Northwest” for Grant).

Tom Hanks takes the cake with Spielberg, appearing in five of his films between 1998 and 2017. If you count Harrison Ford’s deleted scene from “E.T.,” he ties with Hanks. But given that it’s deleted, Ford is awarded second with four appearances, all of them chapters in the “Indiana Jones” sagas. Mark Rylance, Dan Aykroyd, Richard Dreyfuss, and others follow with three.

Steve Wood & Michael Stroud/Daily Express // Getty Images

Awards

It would take 3,000 words alone to detail every award Hitchcock and Spielberg have been nominated for and/or won. Both have won numerous awards from festivals, film institutions, and critics’ circles across the globe, including many honorary and lifetime achievement awards. Spielberg’s films have received 131 nominations and 34 wins at the Oscars (“Schindler’s List” picking up his only Best Picture award) while Hitchcock’s films racked up 50 nominations and only six wins (“Rebecca” snagging his only Best Picture—then called “Outstanding Production”—award). Spielberg won Best Director twice for “Schindler’s List” and “Saving Private Ryan.” Although nominated five times, Hitchcock never won Best Director. His constant snubs by the Academy were a hot topic throughout his career.

Josh McGinn // Flickr

Legacy

Cinema is a different medium without Hitchcock or Spielberg. The former is credited with inventing the suspenseful thriller as we now know it while the latter is credited with making the first blockbuster, the broad genre of film that has now taken over the film industry for better or worse. Longtime New Yorker critic Richard Brody wrote that Hitchcock “has the prime merit of having become the cinema’s exemplary adjective,” Hitchcockian, a word added to the Oxford English Dictionary officially in 2016 after half a millennium of usage.

Of Spielberg, Roger Ebert wrote, “It is likely that when all of the movies of the 20th century are seen at a great distance in the future—as if through the wrong end of a telescope—his best will be in the handful that endure and are remembered.”