From switchboard operators to Zoom: The evolution of workplace communications

Published 5:30 pm Thursday, November 3, 2022

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

From switchboard operators to Zoom: The evolution of workplace communications

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed how people communicate at work: Nearly half of people videoconference more, 43% email more, 42% call more, and 41% text more than before the pandemic, according to a data analysis from Grammarly.

To track the evolution of business communications from switchboards and fax machines to email and VoIP systems, Top10.com compiled a list of nine milestones that transformed how we collaborate in the workplace, using research from technology publications, newspaper archives, the International Association for Computer Information Systems, and other sources.

Workplaces have often set industry standards in adopting new or more efficient technology to improve day-to-day business. Before we had our own telephone at our desks—and well before we had them in our pockets—switchboard operators made it possible for a client or coworker to reach you directly to talk business in real time.

When it came to sending files, documents, and forms, businesses ditched hand couriers and the post office in favor of the fax machine, which became an office staple in the ’80s. It wasn’t long after that when email, though initially used for personal communication, became a large part of office life and has led to an “always-on” email culture. Videoconferencing, first presented in 1968 as a commercial solution, has undergone many iterations and remains a steady presence in workplaces to this day, allowing for remote work.

Read on to learn how cellphones, instant messaging, Zoom, and other tech have influenced workplace communication.

![]()

Topical Press Agency // Getty Images

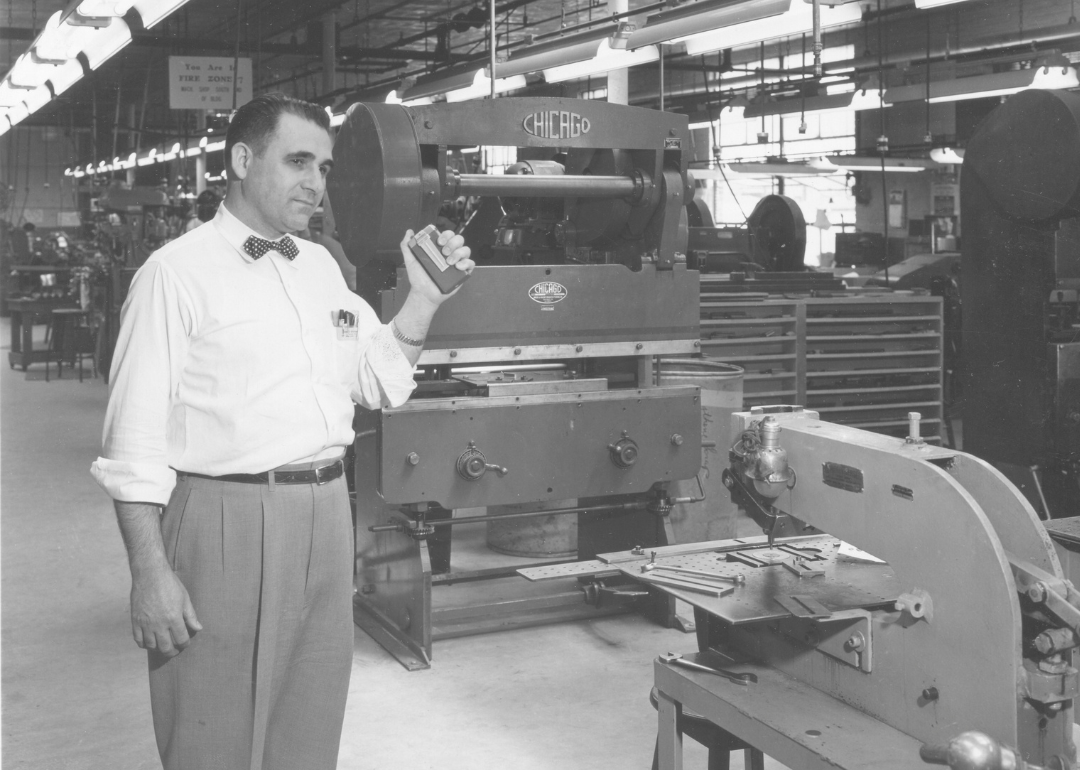

Switchboard operators

The telephone transformed communications in the office, allowing white-collar offices to separate from warehouses and factories. This ultimately, and perhaps ironically, made American offices more centralized.

In the early days of the telephone, switchboard operators were essential intermediaries who relayed calls manually through a central switchboard connected to subscriber wires.

George W. Coy, who had experience in the telegraph business, came up with the idea for switchboards after attending a lecture by telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell: Together, they started the first American telephone exchange. This technology, which began as one exchange with 21 clients, revolutionized the telephone and made it available to the masses.

Women dominated the switchboard operator field in the early 20th century, growing from 88,000 in the U.S. in 1910 to 235,500 by 1930. Soon telephone users could call each other directly, leading to widespread job cuts. By the ’40s, there were fewer than 200,000 switchboard operators.

PhotoQuest // Getty Images

Pagers

The pager was invented in 1949 by Al Gross, a man whose attempts to interest hospitals and telephone companies in his newfound technology were mostly unsuccessful—except for New York’s Jewish Hospital, which implemented pager use in 1950.

Pagers peaked in the ’90s after Gross’ patents had expired, with pagers worldwide reaching 61 million in 1994.

Pagers were and still are most frequently used in hospitals, where the devices were praised for improving and accelerating urgent communications. They’re still useful today, with signals that can penetrate buildings, making them more reliable than cell phones.

As of 2017, nearly 80% of U.S. hospitals still rely on pagers for their communications, according to a study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. Other companies still using pagers as of 2017 include infrastructure companies like EDF Energy in the U.K., lifeboat crews using pagers with GPS trackers, and emergency responders or medics.

Reg Innell // Getty Images

Videoconferencing

Videoconferencing technology was first introduced at the World’s Fair in New York as “the Picturephone,” a commercial solution with which users could communicate over video in 10-minute intervals. The initial adoption was slow because it was a clunky, expensive device that required a challenging setup.

Videoconferencing didn’t become popular until the ’80s when the price for such a system dropped from at least $250,000 to $80,000. The computer revolution in the same decade led to the combination of computers being used in the workplace and the use of an integrated services digital network and broadband services, which helped videoconferencing become more viable.

These early efforts were still expensive and complex, discouraging many companies from using this technology.

Tech advancements in the ’90s including major Internet Protocol technology, video compression, and internet advancements helped nudge the price down for IBM’s videoconferencing systems to $20,000. In the same decade, webcams allowed videoconferencing technology to reach consumers. However, as in the ’80s, videoconference solutions did not always offer the best user experience because there was a tradeoff between motion-handling capacity and picture resolution.

By the early aughts, Skype provided a software technology solution for video transmission that significantly improved that technology; by the mid-’00s, the webcam became a standard desktop and laptop component. At that point, companies also started seeing the financial rewards that came with videoconferencing: increased employee productivity, reduced travel expenses, and savings on real estate and other office-related costs companies still get to this day. And, of course, there are the significant changes videoconferencing technologies brought to workplace communications during the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing people working from home to attend Zoom meetings.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Fax machines

Fax machines send graphic or text messages through a phone line from a scanner to a printer, which prints the message on paper. Because phone lines can only pick up audio, the original message is converted into frequencies and tones that the machine interprets as either white or black, which results in the printed page’s overall composition.

This first version of the fax machine was invented by Xerox in 1964, though the technology itself—the electric printing telegraph—was created in 1843 by Alexander Baine. In the late ’70s, mostly Fortune 500 companies used them to get and send urgent documents. The devices were widespread by the ’80s and used across government, medical, legal, and small-business offices. Ubiquitous use drove prices down: Fax machines cost $18,000 in their heydey, dropping to as low as $500 by 1991.

Fax machine technology was the fastest-growing business communication and office automation area at the time, as fax machines could transmit documents between rooms in the same building or over thousands of miles. Until cellphones started replacing landlines late in the ’90s, fax machines facilitated all kinds of office communications.

As home landlines became less common, the number of consumers using fax machines declined. However, some industries—such as tech, finance, insurance, and health care—still use fax machines to send secure communications that follow strict privacy policies, such as the federal law restricting the release of medical information.

The Washington Post // Getty Images

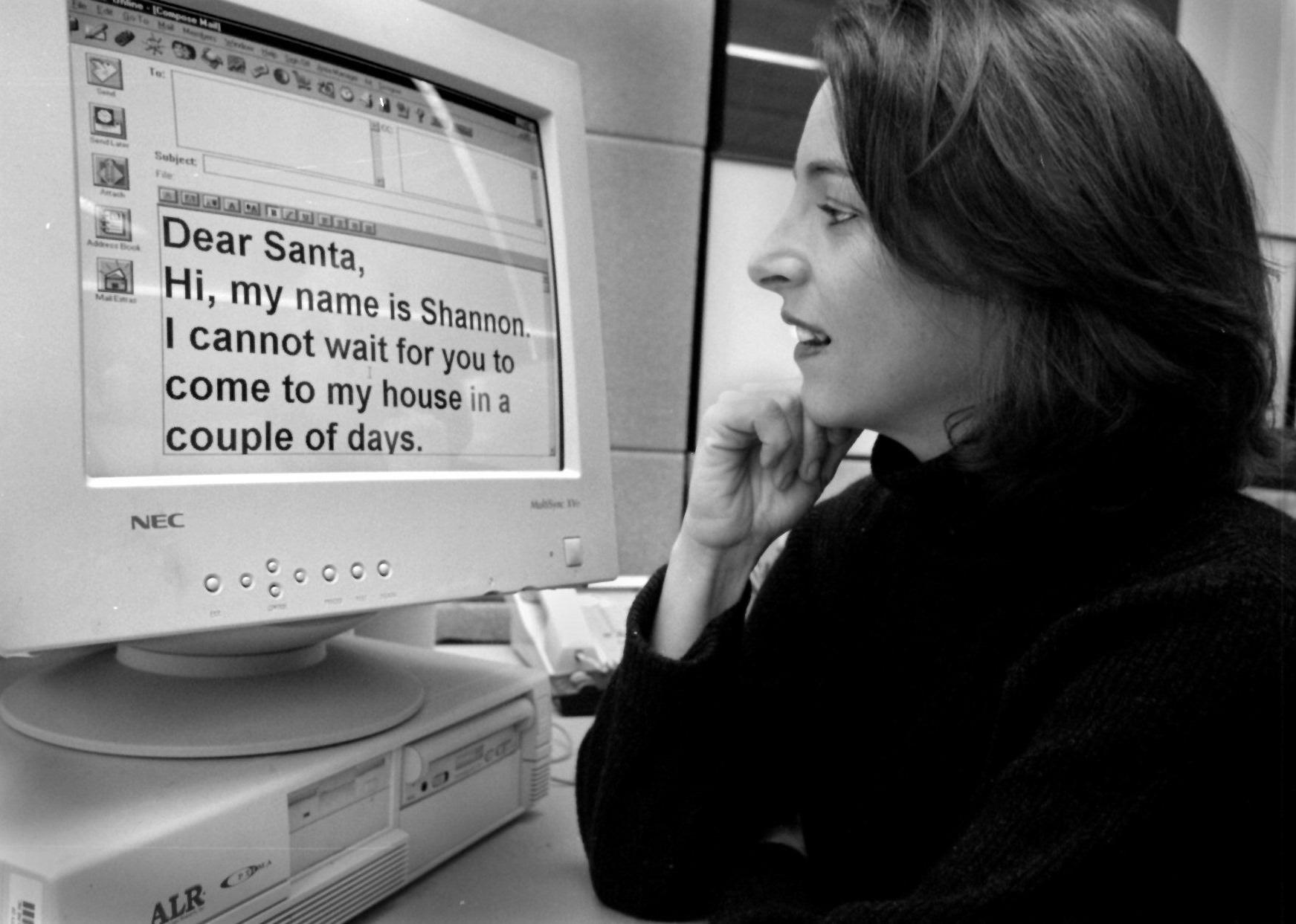

Ray Tomlinson created the first electronic mail, or email, system in 1971—though it wasn’t until the World Wide Web’s inception that email became popular. By the ’90s, email was an essential communication tool worldwide. 1993 brought a new milestone: Users could attach files to emails.

While many people used email personally in the ’90s, sending speedy replies wasn’t the norm, and people even considered faxes to be still more effective. Email became all-pervasive in the office in the 2000s, and the way professionals worked quickly transformed. Suddenly, people became obsessed with checking their inboxes, spending hours sending and receiving messages, and worrying about email etiquette’s undefined rules.

Now, email culture is “always-on,” with employees receiving emails during their off-work hours, like in the evening or over the weekend.

Ron Watts // Getty Images

Cellphones

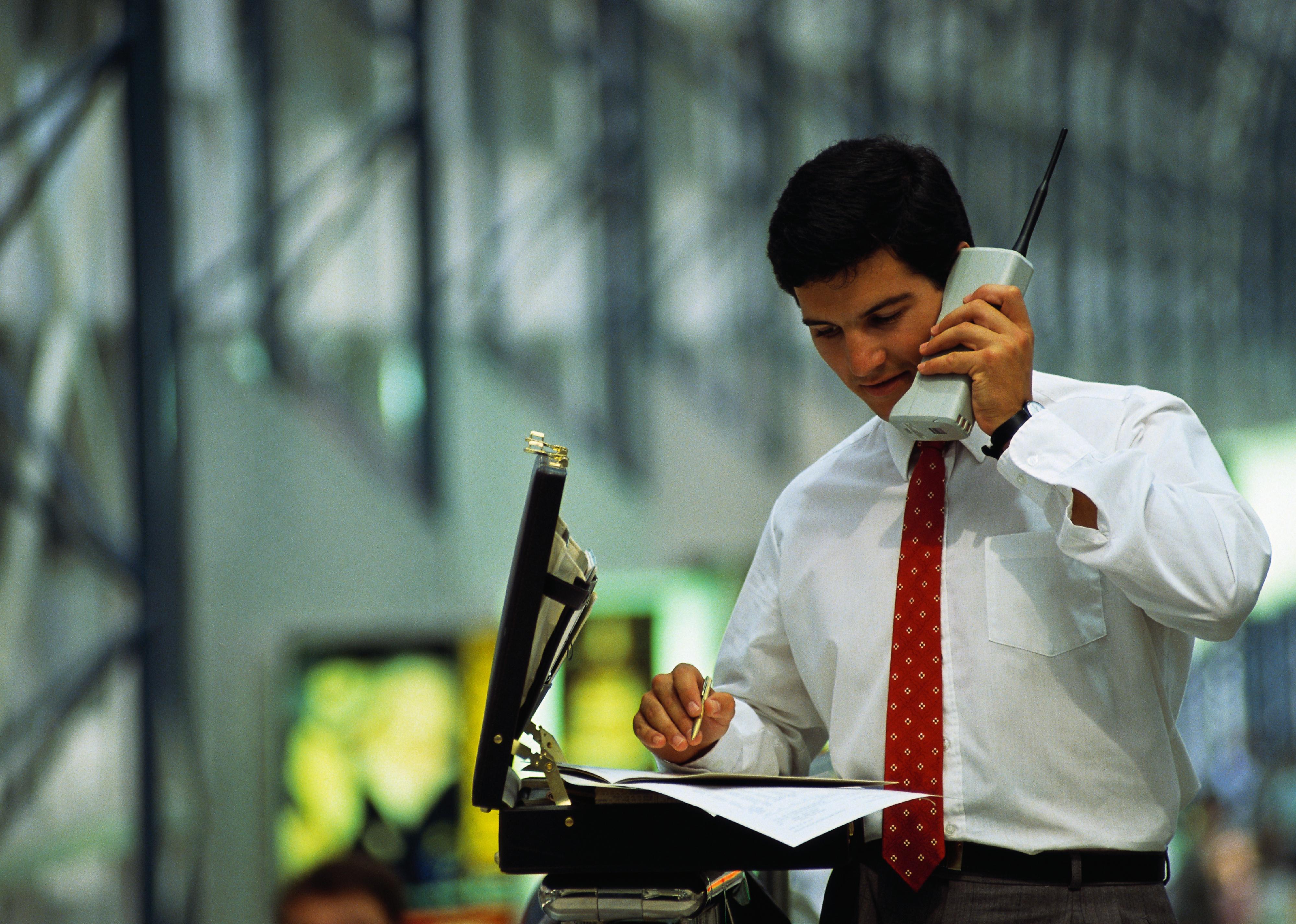

The first call made from a cellphone was by Motorola executive Martin Cooper in 1973—and the device was pretty different from the cellphones we use today, weighing around 2.4 pounds, resembling a brick, and only being able to put a call through for 30 minutes after charging for 10 hours.

It wasn’t until 1983 that the first commercial phone came out, Motorola’s DynaTAC, a heavy, bulky device that cost around $4,000. These cell phones became smaller throughout the ’80s, culminating in 1989 when the release of Motorola MicroTac, a flip phone that could fit inside a user’s shirt pocket. Around the beginning of the 21st century, many affordable cellphones came out with various features: web browsing, a function similar to today’s touchscreen feature, full physical keyboards, a camera, a color screen, and fashion features like a variety of colors and sleek design.

In addition, there was the car phone, invented in 1920. The device—only available in luxury cars and to the rich and famous—was considered an eccentric invention until the ’40s and ’50s when cellphone towers were erected in the U.S. In the ’70s, car phones finally reached the masses, but they soon fell out of fashion when cellphones became popularized in the ’80s and ’90s.

In 1990, a Canadian program called Venture interviewed car phone users—an owner of a small business, a professional in the travel industry, a sales agent, and a building contractor—and they all cited business as the main reason for using a car phone. One user reported that it was never possible to “get away” and that they could be reached “all the time,” though others used the tech for personal calls.

David Paul Morris // Getty Images

Instant messaging

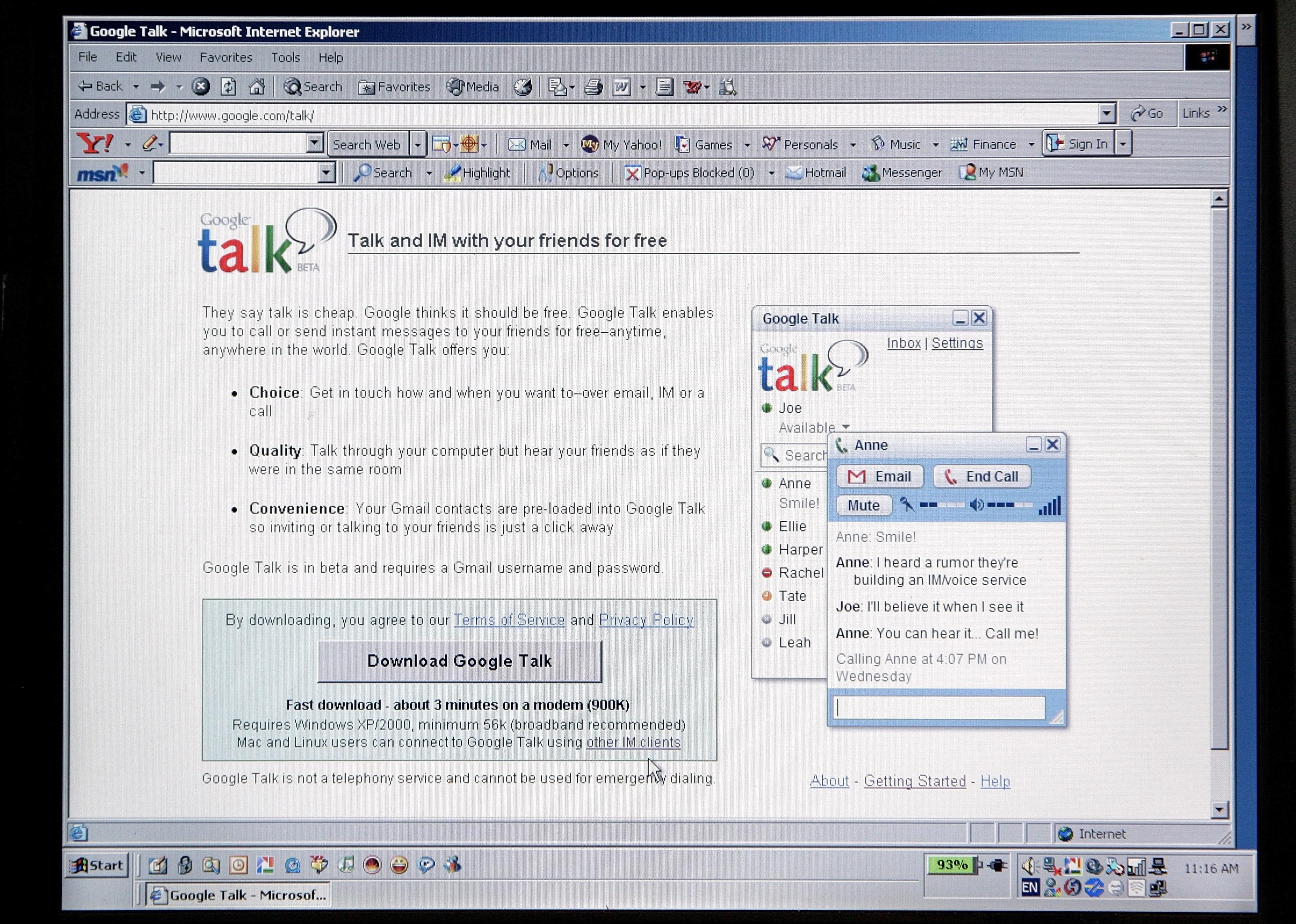

Instant messaging dates back to 1961, when the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Compatible Time-Sharing System allowed 30 people to log in and send each other messages.

The rise of the internet in the ’90s caused instant messaging to take off, and major IM platforms, including Yahoo, MSN, AIM, and ICQ, began competing in the market. IMs flourished in the ’00s as playing games, making video calls, and sharing photos became common IM features of new IM platforms like Apple’s iChat, Skype, Google Talk, MySpaceIM, WhatsApp, and Facebook Chat (now Messenger).

Another major transformation occurred in the 2010s when such apps as WhatsApp, WeChat, Snapchat, Discord, and Slack offered many new features, including making payments, shopping, sending pictures that disappeared after a specific time, and facilitating workplace communication and collaboration.

When the pandemic required many workers to start working remotely, IM communication platforms such as Slack and Microsoft Teams helped workers collaborate with their colleagues and continue working efficiently. Slack co-founder Cal Henderson said in an August 2020 Wired UK interview that many major companies would embrace remote working permanently, mainly because of its tools.

Future Publishing // Getty Images

Smartphones

The first smartphone, the Simon Personal Communicator, was unveiled by IBM in 1992; two years later, it was available on the market for $1,100. While it wasn’t sleek or compact, it had many features that persist in smartphones today, such as a touchscreen, standard and predictive text keyboards, a native appointment scheduler, a calendar, an address book, and email. It could even send and receive faxes.

The first smartphone connected to a 3G network became available in the early 2000s, but given that it cost between $300 and $700, it was a bit pricey for most people. But when the iPhone debuted at Macworld in 2007, the public was presented with a phone that had a sleek design and internet access similar to a desktop computer. Since then, many new versions of the iPhone have been released, the Android has come out, apps have been on the rise, and the number of smartphone users worldwide has gone up significantly to 83.3% of the global population as of October 2022.

Smartphone use has impacted work-life balance, with employees dealing with personal affairs at work while completing work tasks during their free time. These devices have facilitated faster information flow; face-to-face meetings through messages, email, or video conferences; flexibility in work location; and higher employee satisfaction. On the other hand, they have led to declining productivity, ongoing stress, and the loss of privacy.

Smartphones also centralize many tasks, enabling people at work to look at their invoices, talk to coworkers, and send emails in one place without going to the office. This meant many of the tasks covered on this list could now be done on a smartphone.

Girts Ragelis // Shutterstock

Zoom

Eric Yuan founded Saasbee Inc. in 2011, renamed it Zoom the following year, and unveiled Zoom 1.0 worldwide in 2013. But the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic seven years later is what truly put Zoom on the map.

After COVID-19 reached the U.S. early in 2020, schools throughout the country closed, provided their students with tablets and laptops, and quickly had educators pivot to teaching via apps such as Zoom. People used Zoom to socialize online when restrictions were in place: celebrating birthdays, hosting trivia nights, and even attending virtual happy hours. And, of course, businesses used Zoom as lockdowns worldwide led to closed offices, making working from home obligatory for many.

While there are other players in the enterprise videoconferencing space—BlueJeans, GoToMeeting, Skype, Google Meet, and Microsoft Teams—it was Zoom, eventually, that would become the most popular. Zoom became so popular that its brand was turned into a verb, as in, “Sure, let’s just Zoom next Monday and talk about it then.”

With Zoom, businesses could communicate in various ways using the videoconferencing solution. They can host one-on-one meetings or town halls with a maximum of 100 participants and multiple communications through the platform, such as group chats, cloud phone calls, webinars, and video meetings. Additionally, the app can be accessed through mobile devices, conference rooms, browsers, and desktop clients, making it accessible to everyone on the team. It’s important to note issues such as “Zoom fatigue” and how the app is not a complete replacement for in-person communication.

More than 7 in 10 executives said hybrid/remote work hasn’t hurt building connections with their employees; they were considering a remote-flexible working model after the success of remote collaboration during the pandemic, according to a July 2022 Morning Consult survey for Zoom. This report also found that videoconferencing technology was one of the most significant factors that contributed to a positive view of remote working. Given the success of remote work during the pandemic, the trend will likely become commonplace in the world of office work.

This story originally appeared on Top10.com and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.