These states have the highest maternal mortality rates—for Black mothers, outcomes are even worse

Published 2:00 pm Wednesday, April 12, 2023

Monkey Business Images // Shutterstock

These states have the highest maternal mortality rates—for Black mothers, outcomes are even worse

April Valentine went to Centinela Hospital in Inglewood, California, on Jan. 9 to give birth to her daughter, Aniya. She never made it back home.

Her boyfriend, Nigha Robertson, said at a Los Angeles County board meeting on Jan. 31 that Valentine’s complaints of pain went ignored for hours. Robertson said he “screamed and begged” for someone to help her as he performed CPR on her while hospital staff neglected to intervene. Aniya was delivered via Cesarean section, and Valentine became the latest Black woman whose tragic death would make her the face of the maternal mortality crisis in the U.S.

Compared to similarly wealthy countries, the U.S. is “the most dangerous place to give birth.” Despite high and steadily increasing health care spending per person, the U.S. health system has worse outcomes than the Netherlands, Canada, France, Germany, New Zealand, Norway, Australia, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Sweden. People in the U.S. die during pregnancy or relatedly within one year after pregnancy at a rate more than three times higher than people in similar countries. Within the U.S., that reality is even more tragic for Black women, and the situation is most dire in a handful of states.

Stacker compiled data from state maternal mortality review committees and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to examine how maternal mortality and pregnancy-related death disproportionately impact Black people.

Editor’s note: While this story centers on maternal outcomes, we acknowledge that not all people who can become pregnant identify as women or mothers. The data presented here is an indication of a larger issue because federal and state data often invisibilizes Indigenous communities.

![]()

Emma Rubin // Stacker

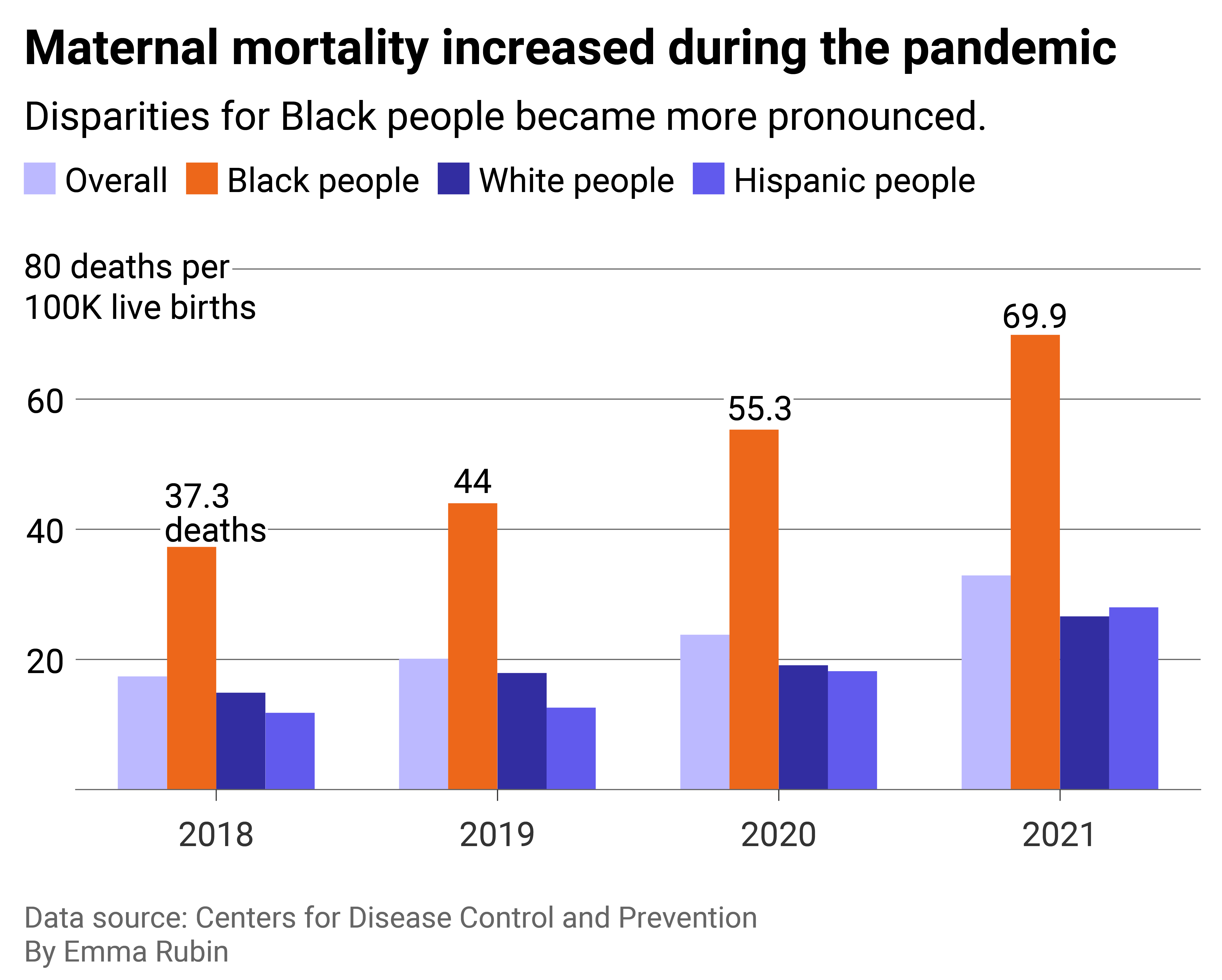

National data shows the disparities Black mothers face

Black women are more than twice as likely to die during pregnancy and the period after childbirth than white women. The CDC defines maternal death as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy.” Pregnancy-related death extends up to one year after the end of pregnancy. In both maternal and pregnancy-related deaths, the cause is related to or worsened by pregnancy. When it comes to pregnancy-related death, Black women are more than three times more likely to die up to a year after the end of pregnancy than white women.

The CDC only started reporting this data in 2018 due to an improvement in data quality. All states began requiring a pregnancy check box on death reporting forms, allowing for better tracking of maternal and pregnancy-related mortality.

In 2020 and 2021, COVID-19, which also disproportionately killed Black people, contributed to 1 in 4 pregnancy-related deaths, according to the Government Accountability Office. This widened the gap even further, both directly and indirectly. The COVID-19 pandemic also changed the way women give birth in hospitals, namely access to doulas and a support person.

COVID-19-related hospital restrictions across the world meant that, for almost two years, doulas could not attend hospital births with their clients. In the U.S., however, doulas or a support person in the delivery room can be the difference between life and death for Black and Native American women. Studies show that to both combat the racism in the medical system and provide culturally competent care, doulas advocate for their clients during labor and delivery as well as in the postpartum period so—like Angel Valentine—their concerns don’t go unaddressed.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

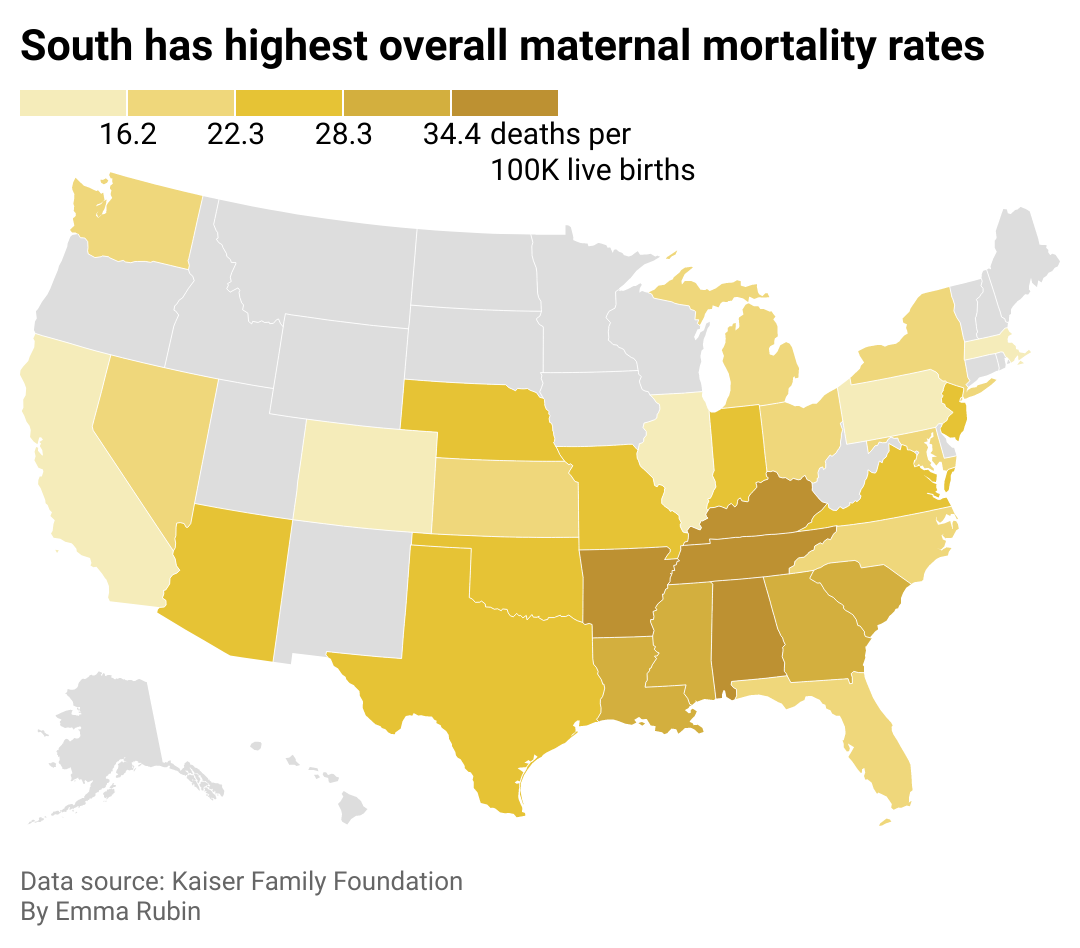

Southern states report worse outcomes overall

Because the U.S. has no universal health care and health policy—and hospital quality and access vary so much across the U.S.—so do maternal mortality rates. In the South, where the states with the highest populations of Black people live and structural racism has left communities impoverished and underfunded, maternal mortality rates are the highest.

Tennesee, Kentucky, Alabama, and Arkansas see maternal deaths at higher rates than other states in the U.S. Notably, all four states have high concentrations of maternity care deserts, where there’s no access to maternal health care. These states also have something else in common: active abortion bans. According to a 2023 report from the Gender Equity Policy Institute, women in states with abortion bans are about three times more likely to die pregnancy-related deaths. By 2021, the maternal mortality rate in states with abortion bans was more than two times higher compared to other states.

While living in maternity care deserts and lack of insurance affect overall maternal mortality rates across states, other factors like persistent segregation within states present a different problem.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

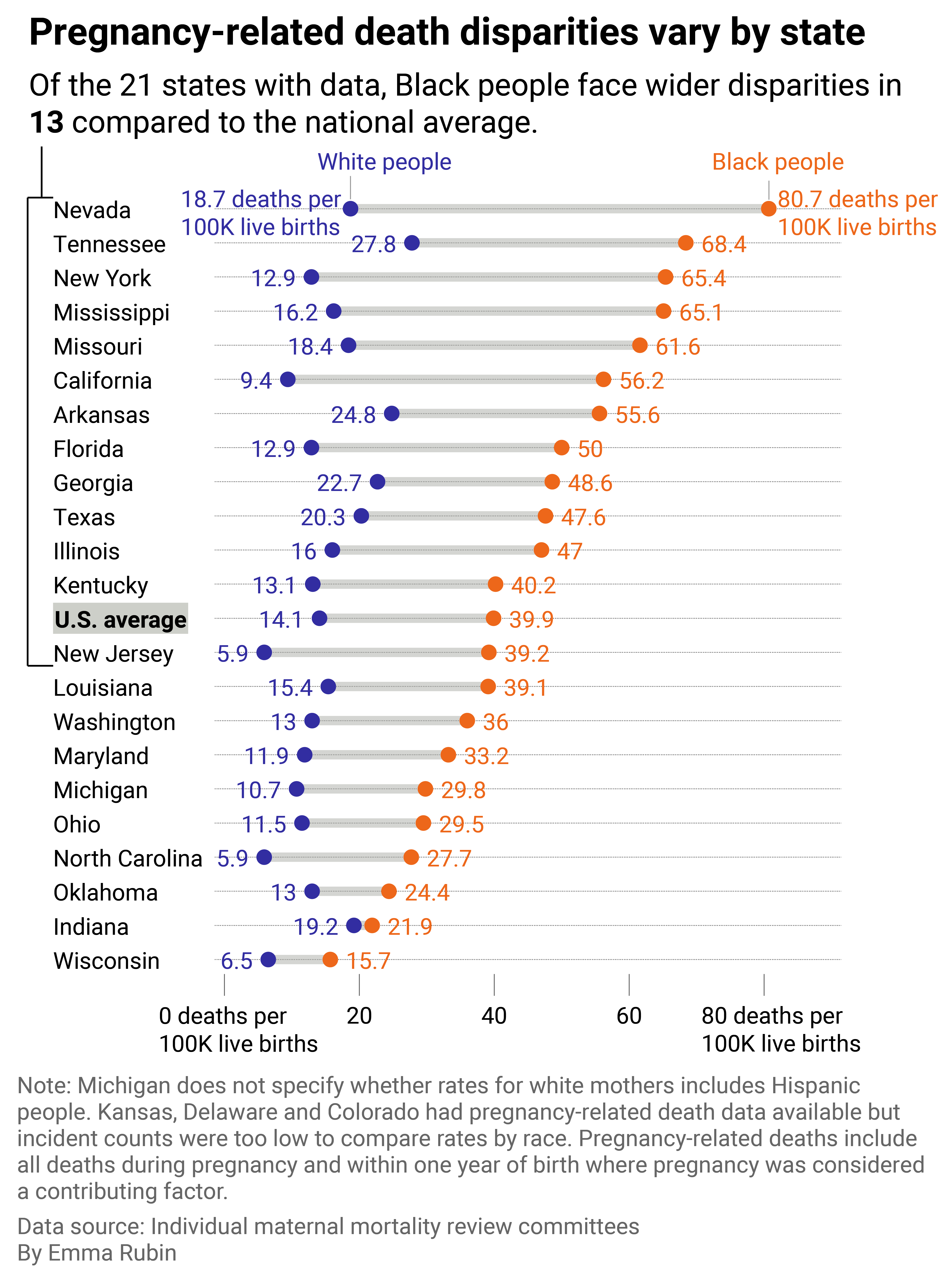

Pregnancy-related deaths data sheds light on local racial disparities

Maternal mortality rates at the local and state level are sometimes suppressed due to low incident counts. This is even more prevalent when showing rates for different races within a state due to low sample sizes. However, data on pregnancy-related deaths is more widely available.

Stacker identified 21 states with rates of pregnancy-related deaths for Black people compared to white people. The analysis period ranges from state to state but provides a basal understanding of racial disparities in pregnancy-related deaths at the state level. Some states report pregnancy-associated deaths but not pregnancy-related deaths, which are not included in the visual above. Stacker is sharing this table featuring the data we collected on pregnancy-related deaths at the state level.

Of those 21 states, the racial disparity is greatest in Nevada, where Black women are four times more likely to die a pregnancy-related death than white women living in the same state. Shockingly, Nevada has the second-lowest maternal mortality rate in the country, behind California, but that is an incomplete story. Cities in Nevada are largely segregated by race, and more than half (52.9%) of the state’s counties are maternity care deserts. Similarly, in New York, segregation and structural racism lend to the large Black-white disparity in pregnancy-related deaths. In New York City, a report by the city’s Office of the Public Advocate cites structural racism, access to care, quality of care, and implicit biases among the reasons Black women have worse outcomes.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

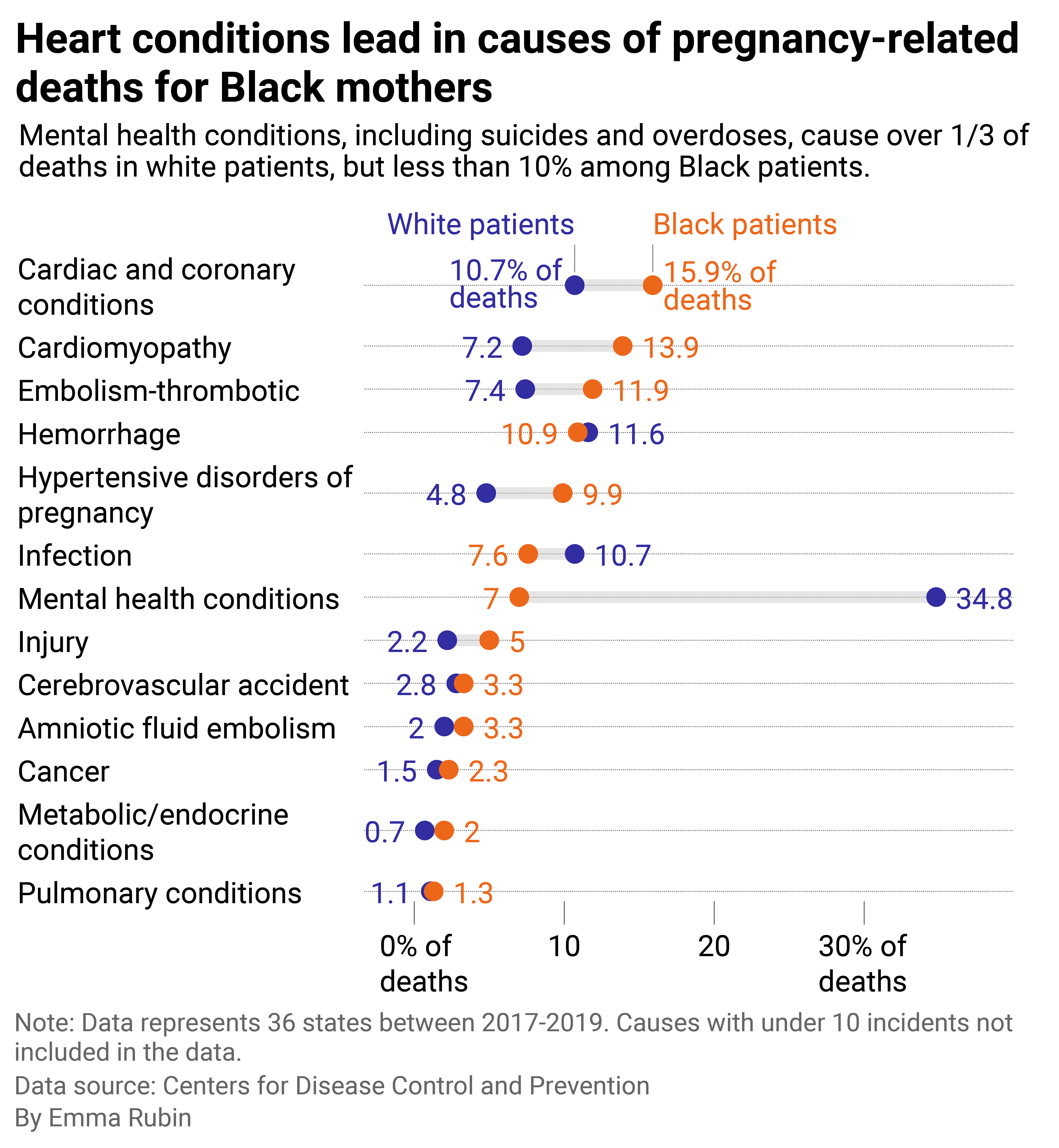

Most pregnancy-related deaths are preventable

Charles Johnson said his wife, Kira, was in “exceptional health” when she died from childbirth in 2016. Kira Johnson had a C-section at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Charles noticed blood in her catheter and other signs that something was wrong. When he begged hospital staff to help her, a nurse told him she was “not a priority.” Kira was hemorrhaging internally, and by the time she was cared for at the hospital, it was too late. Her death was preventable. In fact, 84.2% of all pregnancy-related deaths are preventable.

This fact highlights the need for improved maternal health care at the hospital level, more initiatives at the community level, and stronger policy at the state level to regulate the care pregnant people receive regardless of race, insurance status, and socioeconomic status. Charles, now a maternal health advocate, supports and advocates in front of Congress for key legislation to help stop preventable maternal death, including the Preventing Maternal Death Act of 2018, the Protecting Moms Who Served Act of 2021, and the California Momnibus Act. His organization, 4Kira4Moms, is currently advocating for Congress to pass the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2021 (which includes the Kira Johnson Act), introduced by Illinois Democratic Rep. Lauren Underwood.

“The greatest impact that the federal Momnibus will have on a state level is expanding postpartum Medicare and Medicaid to 12 months postpartum for all mothers,” Charles told Stacker. “In many states, postpartum healthcare cuts off after six weeks, leaving millions of mothers extremely vulnerable.”

Besides improving the quality of care and access to care to address the nation’s high maternal mortality rate, Charles said the U.S. needs policy to address the root of the racial disparities in maternal health: bias and racism.

“The Federal Momnibus, and more specifically the Kira Johnson Act, will provide greater accountability measures for hospitals and providers, including mandatory implicit bias training for all birthing centers and hospitals nationwide,” he said.