25 historic images of Route 66 in its early days

Published 4:05 pm Monday, October 30, 2023

25 historic images of Route 66 in its early days

With cars rapidly gaining popularity in the early 20th century, an American businessman in Tulsa, Oklahoma, had a vision of a network of highways connecting the whole country.

Starting small in 1901 as a businessman and county commissioner, Cyrus Avery was nominated in 1925 to the newly formed Joint Board on Interstate Highways, a federal agency tasked with coordinating, organizing, and numbering the country’s road system.

Officially commissioned on Nov. 11, 1926, and first marked with roadside signs in 1927, Route 66—officially U.S. Highway 66—connected Chicago and Los Angeles, not coincidentally passing through Avery’s adopted hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Just 800 of its 2,500 miles were paved in the new route’s first year.

Ahead of Route 66’s 97th birthday, Stacker curated a slideshow highlighting the construction and early years of the iconic American road.

In Tulsa, highway supporters—including Avery—in 1927 formed the U.S. 66 Highway Association, an advocacy group to promote the new highway to drivers and tourists, as well as to policymakers who could approve funds for paving. The highway became nationally famous and earned the moniker “the Main Street of America.”

A major boost to the road’s popularity came from John Steinbeck’s 1939 book “The Grapes of Wrath,” in which the author nicknamed Route 66 “the Mother Road” and chronicled the fictional Joad family’s trip along the highway from Dust Bowl Oklahoma to the fruit fields of California. In the economic boom following the Great Depression and World War II, families—lured by history, popular culture, and countless tourist attractions—piled into their vehicles and set out to explore Route 66.

The Interstate Highway Act of 1956 heralded the road’s decline, as the smaller U.S. routes were supplanted by massive, multilane interstates. But nostalgia kept the myth alive and even resulted in a resurgence of attention. Much of the original Route 66 received a National Scenic Byway designation, with many stretches featuring tourist attractions, lodging, and food aimed at road-trippers exploring one of America’s most iconic roads.

Keep reading to discover more history of the iconic Route 66.

![]()

UPI/Bettmann Archive // Getty Images

Chicago’s bronze lions

Historic Illinois transportation maps show that one end of Route 66 abutted the Michigan Avenue entrance of the Art Institute of Chicago. At the stairs leading up to the institute, a massive pair of bronze lions stare out. Sculpted by 19th-century American artist Edward Kemeys, they mark the historic start of the Mother Road.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Facing another day of the ‘Bunion Derby’

In early 1928, in part as a publicity stunt to promote the new highway, Illinois businessman and promoter Charles C. Pyle announced a coast-to-coast footrace from Los Angeles to New York City running the length of Route 66 before shifting to other highways to get farther east. Nicknamed the “Bunion Derby” for the damage it was expected to cause its contestants’ feet, the race began on March 4, 1928, and finished on May 26. It was won by Andy Payne of Claremore, Oklahoma, after 573 hours, 4 minutes, and 34 seconds of running, wearing through five pairs of running shoes over more than 3,400 miles.

H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock // Getty Images

A Santa Fe street scene

The La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe, New Mexico, is on the city’s central plaza and claims to occupy the site of a hotel dating back to 1607. A luxurious hotel when its current building was built in 1922, generations of Route 66 travelers passed by with some almost certainly staying the night.

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

‘Okies’ arrive in California

Traveling “the Mother Road” like the Joads in Steinbeck’s novel, Depression- and Dust Bowl-era refugees from Oklahoma sought new opportunities in California. This famous image by iconic photographer Dorothea Lange is described in its Library of Congress record as “Depression refugee family from Tulsa, Oklahoma. Arrived in California June 1936. Mother and three half-grown children; no father.”

American stock/ClassicStock // Getty Images

The original western terminus

When Route 66 was first opened, its western end was at Seventh and Broadway in the heart of downtown Los Angeles. By 1947, when this image was taken, the route had been extended about 15 miles west to central Santa Monica. An unofficial “End of the Trail” marker was erected in 2009 on the Santa Monica Pier.

CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Outdoor basket-weaving

Route 66 connected many sections of rural America. Especially in the early days of the highway, travelers regularly passed by scenes of everyday life, like these basket-makers weaving white oak strips near Rolla, Missouri, in 1940.

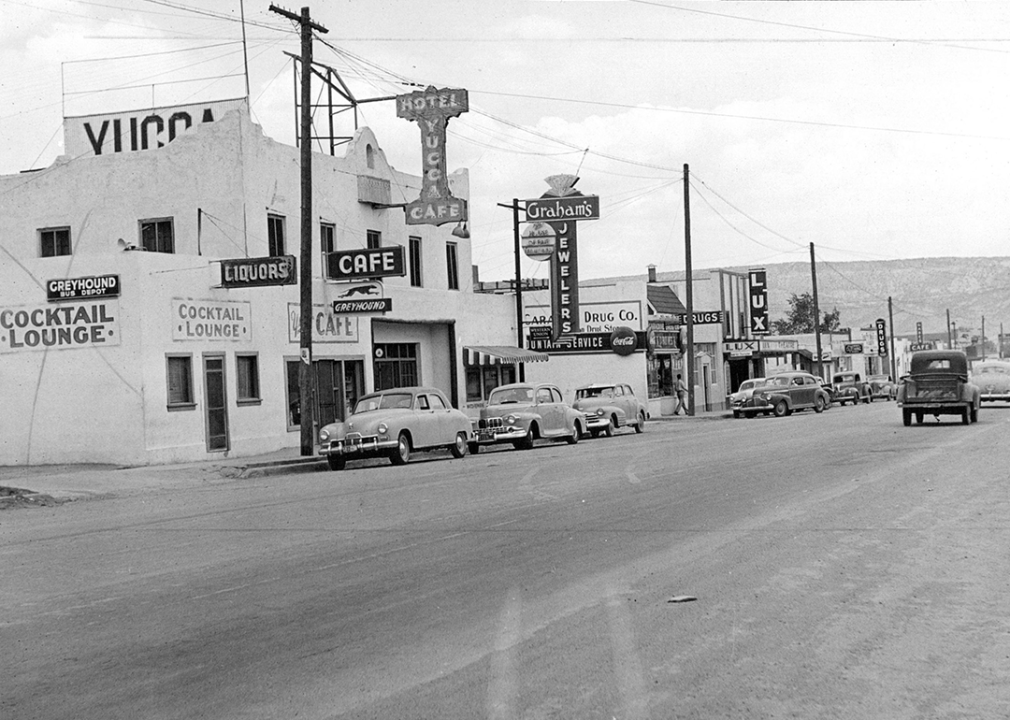

Denver Post via Getty Images

First stop west of Texas

Seen here in 1956, downtown Tucumcari, New Mexico, was a key stopping point for travelers leaving West Texas. Today, the town is home to the New Mexico Route 66 Museum and thoroughly embraces its Route 66 heritage with public art and neon signs.

Jim Heimann Collection // Getty Images

A desert rest stop

Service stations along Route 66 were essential stop points for motorists in need of fuel or food—particularly along western stretches through the desert in states such as Arizona. These businesses, along with others that sprung up to attract passersby, became key elements of the nation’s growing car culture.

University of Southern California // Getty Images

Overnight in Victorville?

About 100 miles east of the end of Route 66 was Victorville, with a downtown hotel and shops on the corner of D and 7th. That neighborhood is the subject of a yearslong revitalization effort to reclaim some of its former glory.

Denver Post via Getty Images

Maybe don’t follow Bugs Bunny?

Halfway from Albuquerque to the Arizona state line is Grants, New Mexico, seen here in September 1950. Drivers who—like Bugs Bunny in several cartoon episodes—missed a tricky left turn in Albuquerque might have needed help getting back on the right road before reaching Grants. Today, the town is home to an art museum with Route 66 memorabilia as well as exhibits of more modern local art.

FPG // Getty Images

The wide-open road

Some of America’s love affair with cars and the open road might be due to vistas like this one from New Mexico in 1940: No traffic in sight, a clear sky, mountains in the distance, and a lovely smooth strip of pavement just waiting to be driven.

T W Kines/US Department of Commerce/PhotoQuest // Getty Images

Iceberg in the desert

Mac’s Iceberg Cafe and Gas Station, found on East Central Avenue in Albuquerque, was a classic only-in-America, only-on-Route-66 roadside attraction designed to make a spectacle—and a must-stop destination—for tourists. Of course, ice cream and gas were major attractions of their own for weary travelers.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Heading east

During the early 1940s, the war effort brought people from all over the U.S. to California factories and shipyards. After the war, people headed back to where they came from—including the family pictured here, pulling a trailer behind their vehicle on their way from California to Minnesota less than two weeks after Japan surrendered.

Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos // Getty Images

Making connections

Finished in 1965, the Gateway Arch in St. Louis reflected the nation’s urge for westward expansion. It was visible to anyone driving on Route 66 across the Mississippi River.

Archive Photos // Getty Images

A namesake of the highway

Will Rogers, an Oklahoma native, was an early multimedia star known for performances in vaudeville and Broadway shows, movies, and radio spots, and for writing humorous and sharp political commentary in newspaper columns around the country. A member of the Cherokee Nation, he became known as the “Cowboy Philosopher” for his witty insights and clever sayings. The New York and Hollywood star drew attention around the world, which he traveled extensively before being killed in a 1935 plane crash in Alaska. Rogers was memorialized with a statue and museum in Claremore, Oklahoma, along Route 66.

Walter Leporati // Getty Images

Check out the Gila monster

The Tomahawk Trading Post outside Albuquerque offered many enticements to draw tourists in, including a live Gila monster. It was not nearly as large as the painted sign might have suggested.

Smith Collection/Gado // Getty Images

A commercial thoroughfare

Though wildly popular with tourists, Route 66 was originally envisioned as a boost to commerce. Trucks like this one photographed in 1968 carried freight all along it for decades until wider, faster interstate highways were built.

Ernst Haas // Getty Images

Passing through the Duke City

The road was wide and busy as Route 66 travelers drove through Albuquerque in 1969. Gas stations, hotels, and fast food were all eager to attract customers on the Mother Road.

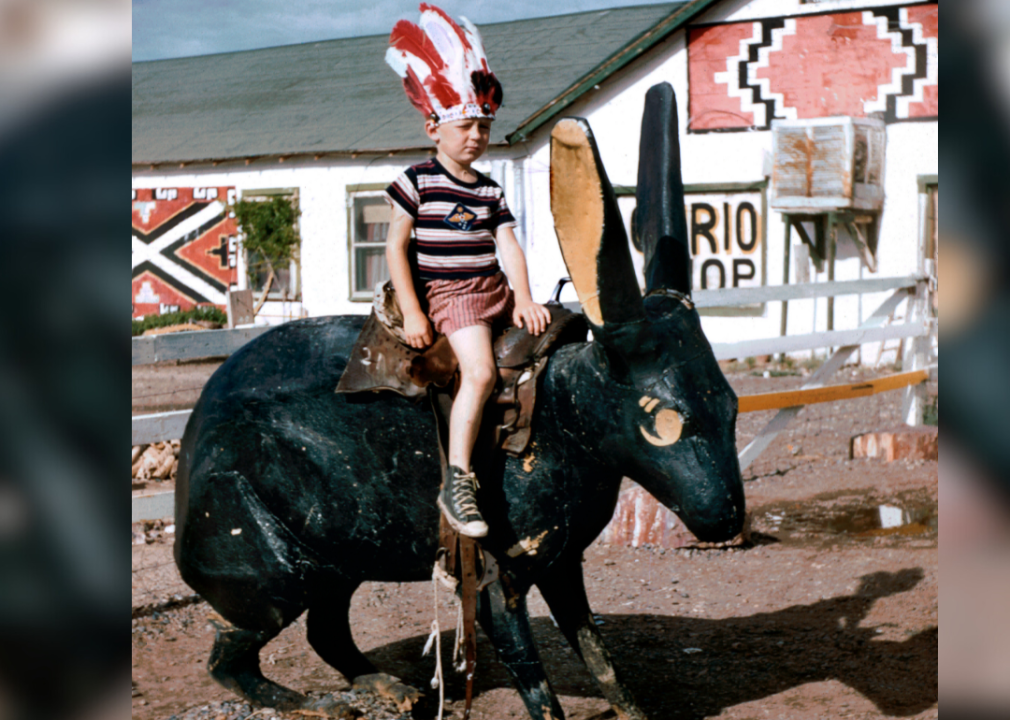

Robert Alexander // Getty Images

Souvenirs and novelties

The Jack Rabbit Trading Post near Joseph City, Arizona, was one of many roadside attractions along Route 66. It’s still there, but sometime since this 1958 photo a different statue of a jackrabbit has been installed out front. Souvenirs like the one the child is wearing here often echoed stereotypes of the time period and highlighted the fact that the road passed through Indigenous lands.

HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

On a corner in Winslow, Arizona

Native Americans found opportunity along Route 66—and still do—with an online tour guide to American Indians and Route 66 produced by the American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association. In this photo from 1979 in Winslow, Arizona, a roadside stop displays and sells local Native American arts and crafts.

Nik Wheeler // Corbis via Getty Images

Through a harsh landscape

As Route 66 passes through the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, vistas open in front of the windshield and the true expanse of the American West becomes apparent.

Francois LE DIASCORN/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

The Boss loved it

Just along Route 66 in Amarillo, Texas, is the Cadillac Ranch, where 10 old Cadillacs are partially buried, hoods down, as monuments to car culture—and, as Bruce Springsteen had it in his 1980 song—a metaphor for how what once was valuable often becomes disposable. It’s still there drawing tourists today.

HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Save a horse?

The Cowboy Motel in Amarillo, Texas, seen here in 1977, was one of many roadside lodgings that traded on kitsch and stereotypical Western themes to draw customers.

HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The Wigwam Village Motel

The Wigwam Village Motel in Holbrook, Arizona, pictured here in 1979, still offers travelers a chance to sleep in structures inspired by traditional Native American teepees—intentionally misnamed “wigwams” by the non-Indigenous architect who designed them. The motel is on the National Register of Historic Places because of its significance to Route 66 heritage.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The end of the road

From the late 1930s, Route 66 officially ended at the corner of Lincoln and Olympic boulevards in Santa Monica. But that wasn’t a very dramatic location, so the unofficial end became the entrance to the Santa Monica Pier.

Story editing by Nicole Caldwell. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.