The Emancipation Proclamation in practice: A timeline

Published 6:00 pm Thursday, December 21, 2023

The Emancipation Proclamation in practice: A timeline

In many Americans’ recollections, the Emancipation Proclamation was a landmark piece of legislation that officially abolished slavery in the United States. But, like many important historical moments, the truth is more complicated.

Jan. 1, 2024, marks 161 years since the day the Emancipation Proclamation was announced by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863. At the time, the Civil War had been raging for three years. Lincoln’s declaration was a watershed moment in the war, which up until then had been formally fought with the central goal of keeping the Confederacy from seceding from the Union. The Emancipation Proclamation changed that, however, and explicitly redirected the struggle toward ending slavery in the United States.

However, the language of the Proclamation was limited in scope. Although it famously declared that “all persons held as slaves … are, and henceforward shall be free,” this didn’t apply to all states and was conditioned on a Union victory in the Civil War. Ending slavery began with the Emancipation Proclamation—but it would be years before former enslaved people gained citizenship, suffrage, and the ability to hold public office.

Stacker used historical records, academic commentary, and political reporting to describe the key events following the Emancipation Proclamation that led to the full abolition of slavery. In reality, the road to freedom was a yearslong process of political legislation and cultural shifts; history, however, tends to remember dramatic moments the best, especially those with such moving and empowering language as the Emancipation Proclamation contained.

Though the events covered here end with the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, the advancement of emancipation continues far beyond this—even more so when one broadens the concept of “freedom” to encompass the larger freedoms of African Americans in general.

For instance, at the same time that formerly enslaved people were first being granted basic rights in society, the Ku Klux Klan emerged in 1865 with the agenda of squashing these efforts. It wasn’t until 1870 that Hiram Revels was elected to the Senate as America’s first Black senator. It took nearly a century after that for the Supreme Court to rule that “separate but equal” schooling policies inherently denied African Americans equal protection under the Constitution.

Read on to discover what it took beyond the Emancipation Proclamation to make formerly enslaved people full, recognized members of the United States.

![]()

VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images

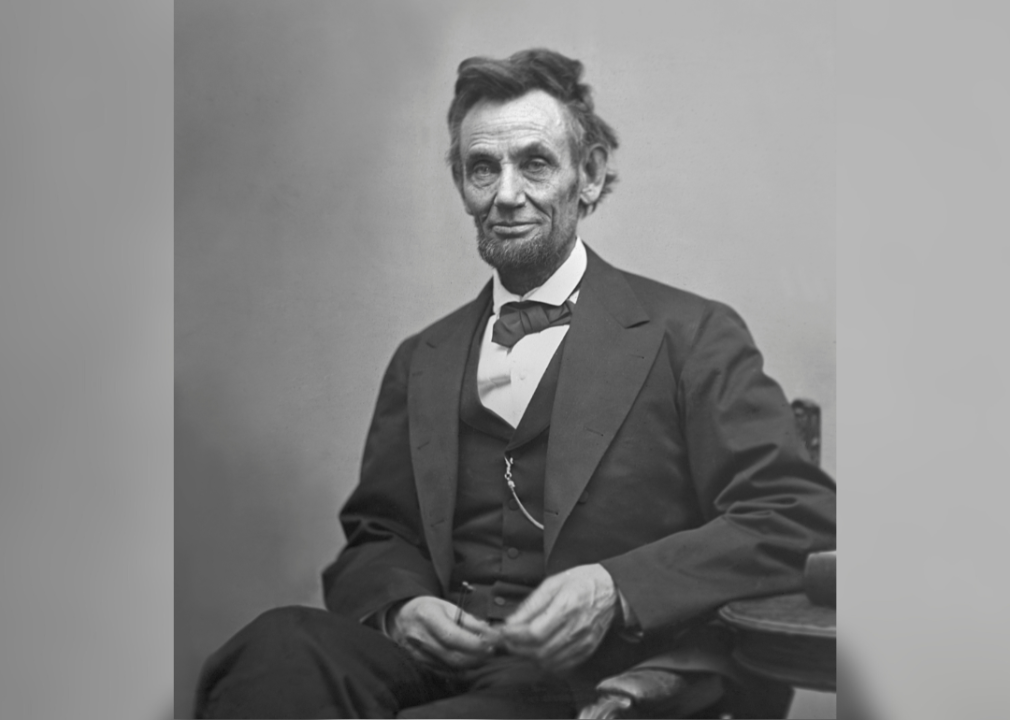

1863: The Emancipation Proclamation is issued

On Jan. 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation—but despite popular cultural opinion, it did not actually end slavery in the United States. This was partially because of its limited wording: Though it stated that “all persons held as slaves … are, and henceforward shall be free,” this only applied to states that had seceded from the Union. Loyal states and some members of the Confederacy the Union had captured were exempt.

Perhaps most importantly, the promised freedom of enslaved people was conditional. It would only be granted if the Union won the Civil War, which, at the time of the Proclamation, was in its third year.

The Emancipation Proclamation also stated men of color would be allowed to join the Union army, an invitation they gladly accepted. By the end of the Civil War, nearly 200,000 Black men had fought as soldiers for the Union.

Carol M. Highsmith/Buyenlarge // Getty Images

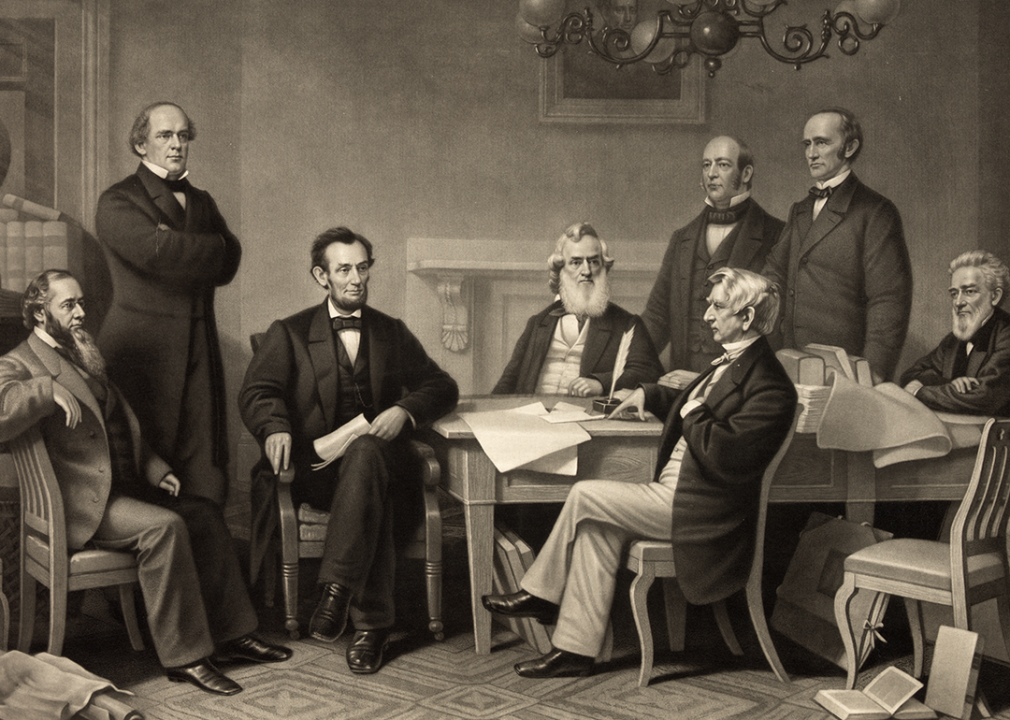

1863: Lincoln meets with Frederick Douglass

Famed freedom champion Frederick Douglass, a formerly enslaved man, had a particular gripe concerning the abolition of slavery: He believed enslaved people could only find full liberation by participating in the Civil War.

After the Emancipation Proclamation was declared, Douglass finally had the go-ahead to begin recruiting the first official regiments of Black soldiers into the Union Army, including his two sons. During the war, many of these soldiers faced torture and reenslavement by the Confederate army. Douglass was so enraged he publicly criticized President Lincoln for neglecting to protect them, resulting in the two meeting at the White House for the first time on Aug. 10, 1863.

The meeting went reasonably well. Though Lincoln couldn’t address Douglass’ grievance on equal pay for Black soldiers, he agreed to sign any commission for Black soldiers the secretary of war recommended.

Douglass was invited to the White House at least three more times by Lincoln and was present at the president’s swearing-in for his second term, during which he publicly declared that slavery was “one of those offenses which in the providence of God must needs come.”

Fotosearch // Getty Images

1863: The Conkling letter

Just a few weeks after meeting with Frederick Douglass, a letter from Lincoln to old friend James C. Conkling was read publicly at a mass meeting of Unionists in Springfield, Illinois. The location was timely and deliberate: Lincoln knew Union Democrats and Republicans were becoming concerningly polarized in Illinois, divided over varying opinions on the cause of the Civil War and the emancipation of enslaved people. The Conkling letter addressed this directly and bluntly, defending the Emancipation Proclamation in no uncertain terms.

In it, Lincoln wrote, “You say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then exclusively to save the Union. I issued the proclamation on purpose to aid you in saving the Union. Whenever you shall have conquered all resistence to the Union, if I shall urge you to continue fighting, it will be an apt time then for you to declare you will not fight to free negroes.”

Reception to the public reading was enthusiastic and widespread: The entire letter was printed in its entirety in national letters in the days following, and it sparked a rally of over 50,000 in Springfield who met Lincoln’s words with cheers and tears.

Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images // Getty Images

1863: The Gettysburg Address

On Nov. 19, 1863, Lincoln delivered a remarkably short but undeniably impactful speech at the cemetery’s dedication at Gettysburg, the site of the deadliest battle of the Civil War. Lincoln’s speech followed the words of famous orator Edward Everett, who spoke for more than two hours beforehand. He later lamented that he failed to have as much impact as Lincoln achieved in just two minutes.

In his speech, Lincoln famously remarked that the “great task remaining before us, that from these honored dead we take increased devotion” to ensure “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.” Though he only referred to slavery opaquely as it fell under the umbrella of ‘freedom,’ the speech still marked the first time he noted the abolition of slavery as a stated goal of the Civil War.

His speech resulted in mixed reviews from papers that both panned and praised this speech. While Republicans (Lincoln’s party) mostly stayed loyal to the president, more radical Democrats felt Lincoln’s words reframed the justification for war, not to keep states from seceding but to free enslaved people.

Just a year after Lincoln publicly delivered the Gettysburg Address, a version of it was published and spread nationally in “Autograph Leaves of Our Country’s Authors.” It is remembered as one of America’s most pivotal speeches.

Glasshouse Vintage/Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

1863: The Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction

Lincoln’s remarks for his annual message to Congress were highly anticipated in 1863, as the general public expected it would indicate the president’s plans for reconstruction. Not expected, however, was the Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction: an official pardon, acceptance into the Union, and restoration of property—except enslaved people—to members of the Confederacy who vowed to accept the Emancipation Proclamation.

The Proclamation introduced the Ten Percent Plan, which laid the groundwork for rejoining the Union and Confederacy by accepting the readmission of the Confederate States, where 10% of voters declared allegiance to the Union.

Lincoln likely aimed to use the Ten Percent Plan to coax Confederates into accepting the Emancipation Proclamation by making it conditional with land retention. The Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction was initially relatively well-received by Unionists, including both Democrats and Republicans.

MPI // Getty Images

1865: Congress proposes the Thirteenth Amendment

Lincoln realized the Emancipation Proclamation alone would not be enough to ensure the full liberation of the enslaved; it would have to be accompanied by a constitutional amendment. The Thirteenth Amendment, which proposed the abolition of slavery, was first passed through the Senate in April 1864; it did not initially pass through the House, however, causing Lincoln to add it to the Republican Party platform for his 1864 bid for reelection. This strategy worked, and the House passed the bill proposing the amendment in January 1865, after which Lincoln submitted the Amendment for ratification by state governments.

The Thirteenth Amendment was officially ratified on Dec. 6, 1865. It stated, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” This action marked, at least, a constitutional answer to the question of slavery—although cultural, economic, and social acceptance would still be years in the making.

National Archives // Getty Images

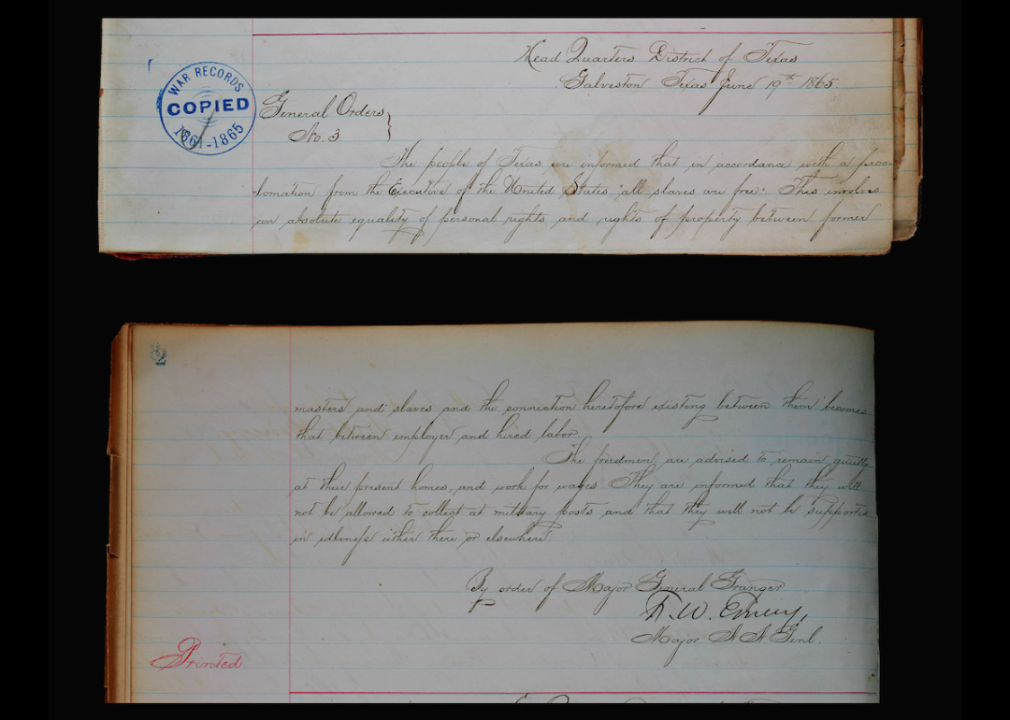

1865: The end of slavery in Texas

Although the Emancipation Proclamation legally went into effect on the first day of 1863, its implementation was far from instantaneous or smooth.

Liberating enslaved persons across the Confederacy was a long process that often required the efforts of Union troops. The most geographically remote Confederate state, Texas, became the final stronghold for slavery, even after the Civil War ended. Many enslavers had migrated into Texas throughout the war, and by 1865, there were an estimated 250,000 enslaved in the state.

On June 19, 1865, Union Troops arrived in Galveston, Texas—posting written announcements from Maj. General Gordon Granger that declared: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages.”

That date, now known as Juneteenth, marks the formal end of slavery in the United States, though, after its official eradication in the Confederacy, two Union border states—Delaware and Kentucky—did not emancipate enslaved people until December of that same year. Juneteenth celebrations began on the first anniversary of Granger’s ordinance just one year later, and today continue nationally.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

1865: Lincoln’s final speech

On April 11, 1865, Lincoln delivered what would be his final public address—though, at the time, no one was aware of its significance. Through his words, Lincoln hinted at his larger plans for reconstruction, including praising Louisiana’s example of abolishing slavery, widening education access to African American children, and allowing some African Americans to vote. Lincoln openly supported the proposition of giving “very intelligent” African Americans the right to vote, along with those who had fought in the Union Army.

One crowd member, however, was fatally unhappy with these remarks: John Wilkes Booth, who turned and remarked to a friend, “That is the last speech he will ever make.” Three days later, Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre.

The Print Collector/Print Collector // Getty Images

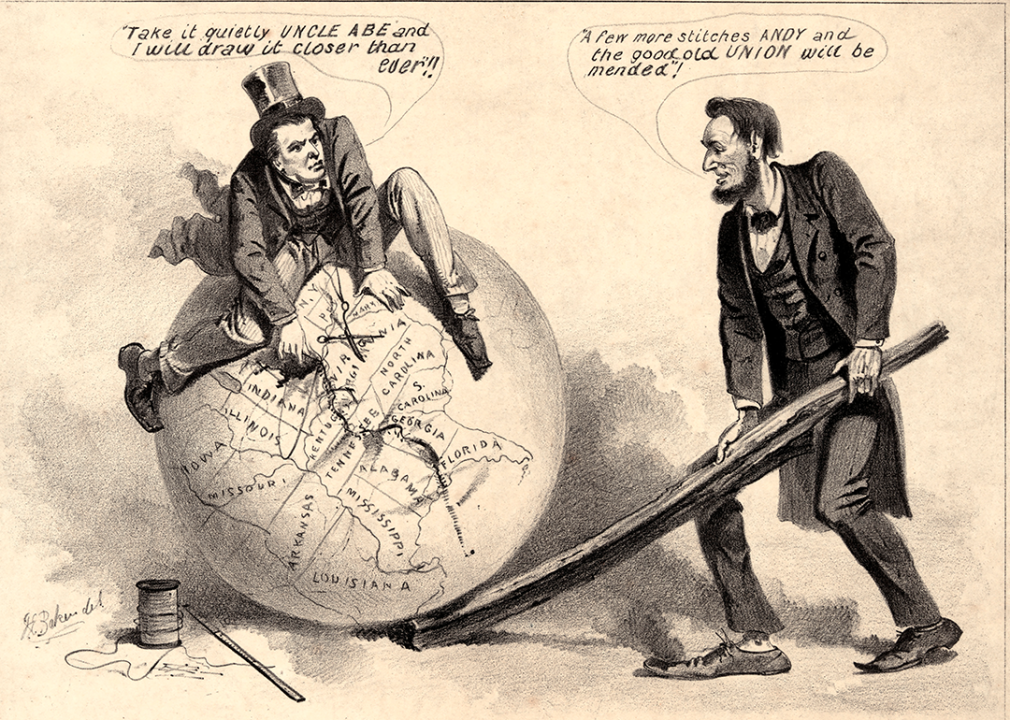

1866: Civil Rights Act

Following Lincoln’s assassination, Andrew Johnson assumed the presidency. Johnson, however, had much less progressive views regarding slavery than Lincoln and thought the Civil War was to preserve the Union, which dramatically altered the path ahead for reconstruction.

Johnson advocated for a policy of “Presidential Reconstruction,” which did not mandate that Southern states guarantee African Americans the right to vote or participate in writing new state constitutions.

When the Civil Rights Act was first proposed in 1866, offering equal rights and citizenship to formerly enslaved people, Johnson vetoed it. Congress met him with opposition, overriding his veto shortly after.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 officially granted African Americans citizenship and equal rights. It also theoretically barred discrimination in significant areas like housing or employment, but officials hardly enforced these protections. It would take another century, during the Civil Rights Movement, for these rights to be fully embraced. However, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 would lay the groundwork for the Fourteenth Amendment.

Buyenlarge // Getty Images

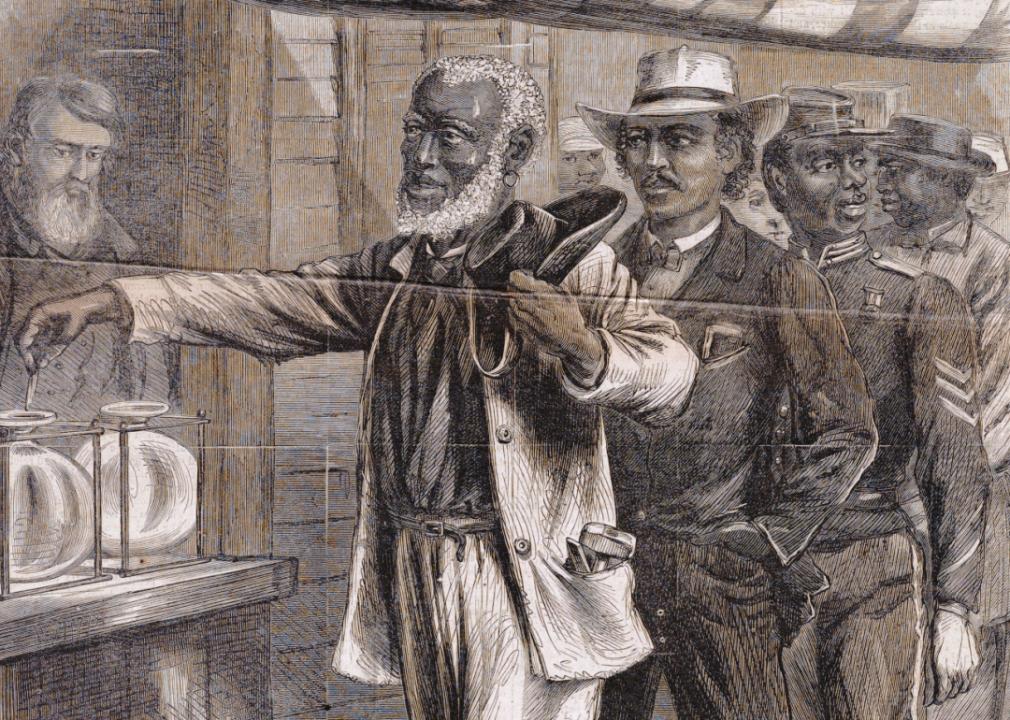

1867: Reconstruction Acts

As the reconstruction progressed, Congress passed a series of acts aimed at solving some of the central questions of how to integrate formerly enslaved people into society, as well as reintegrate Confederate states, despite continued objections from President Johnson.

Congress passed the First Reconstruction Act in February 1867 and proposed the full enfranchisement of all citizens (except for Confederates). When it arrived on Johnson’s desk for review, he attempted to veto it, claiming it would “coerce the people into the adoption of principles and measures to which it is known that they are opposed.”

Frustrated by former Confederate officials attempting to organize governments and undermine Reconstruction in the South, Congress overrode him.

The rest of the Reconstruction Acts would divide the Confederacy into military districts to oversee the establishment of new governments, limit former high-ranking Confederate military officials’ rights to vote and hold office, and, conversely, grant formerly enslaved males those same rights.

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

1868: The Fourteenth Amendment is ratified

In 1857, the Supreme Court ruled in Scott v. Sanford that African Americans—whether free or enslaved—were not U.S. citizens. This ruling was not overturned effectively until the Fourteenth Amendment, which was passed by Congress in June 1866 and ratified in July 1868.

When sending the amendment to the states for ratification, President Johnson declared openly to Congress that his doing so should “be considered as purely ministerial, and in no sense whatever committing the Executive to an approval or a recommendation” of its contents.

The Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States”—including formerly enslaved people—as well as equal protection under the law, stating, “nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The amendment was a landmark in expanding civil rights beyond federal protections by directly addressing states. Its success was limited during the Reconstruction era, however. For years after its passing, the Supreme Court ruled the Fourteenth Amendment did not extend the rights of the first eight amendments to the states. Despite this, it did mobilize Black and white citizens with the promise of what could be.

The amendment’s legacy is more prominently apparent in the 20th century. Its phrase “equal protection of the law” has been used across court cases and enabled several historic civil rights protections in more modern eras, including Brown v. Board of Education (on racial segregation in public schools) and the University of California v. Bakke (on racial quotas in education).

The struggle didn’t end with the Fourteenth Amendment.

The country continues to work for freedom in the 21st century. It is a challenge that continually plays out in modern-day society and politics. As author, poet, and writer Elizabeth Alexander points out, “…freedom does have to do with the condition of being enslaved or not being enslaved. I think we also all know and experience that there is much more to it than that.”

Vote by vote, legislation by legislation, conversation by conversation, the country continues to contentiously make its way toward a truer sense of freedom and a society where all are truly equal.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.