Where in the world do your groceries come from?

Published 2:00 pm Friday, January 12, 2024

Where in the world do your groceries come from?

The radiating public health and safety effect of COVID-19 laid bare vulnerabilities within global supply chains, the resilience of which remains under threat as some countries struggle to return to a state of normalcy, and inflation continues to affect manufacturing, shipping, and product costs adversely.

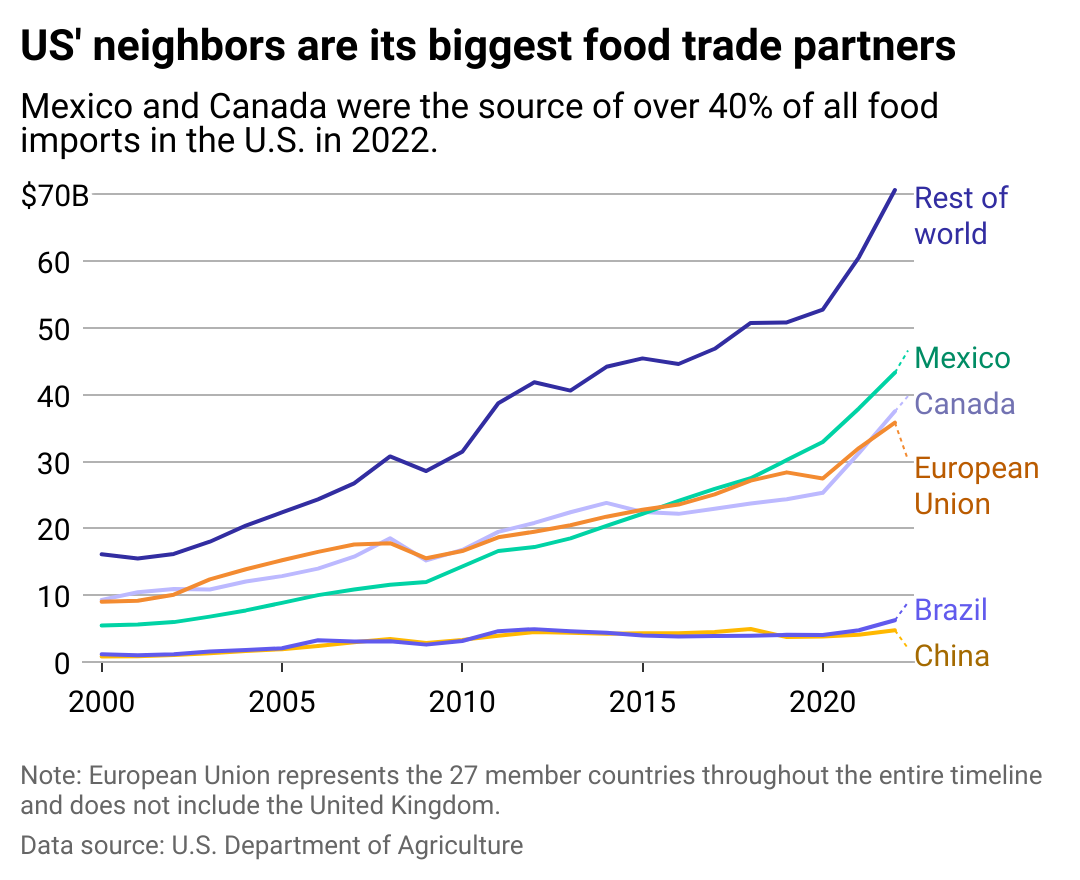

To illustrate how disruptions like these can most heavily impact U.S. food supplies and prices, FoodReady explored which countries the U.S. relies on for food imports using data from the Department of Agriculture.

In the U.S., the pandemic turned grocery shopping and dining habits on their heads in 2020, as restaurant visits ground to a halt and most of the country hunkered down at home. One immediate result of lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, and a general thinning of the national social landscape was that American consumers “made a run” on grocery stores—much as investors have made runs on banks during financial crises. Grocers and big-box outlets alike were caught off guard by the gargantuan demand for food, produce, beverages, and essentials like toilet paper.

Logistics and shipping companies, as well as grocery chains, spent the remainder of 2020 and well into 2021 adjusting their supply chains to adapt to the new habits of an American population trying to avoid infection. Consequently, fresh products, including meat, fish, dairy products, and eggs, were most heavily affected over this period, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

At the same time, the virus’ spread impacted food production at the source. Labor became harder to find and even more difficult to manage safely. By early 2022, the U.S. was emerging from its most virulent strain of COVID-19, with the Omicron variant pushing hospitalizations to a crisis point. What’s more, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—known as the “breadbasket of the world”—in February of that year disrupted one of the world’s most significant sources of grain and agricultural products.

While not one of the largest trading partners to the U.S., the destruction of crops and the widespread violence that severed export operations meant Ukraine produced fewer grains and fertilizer for the rest of the world, pushing grocery prices even higher for consumers around the world, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Bank.

![]()

FoodReady

The US imported nearly $200 billion worth of food in 2022

Mexico, Canada, and the U.S. operate under a trade agreement that lowers barriers to importing and exporting various goods, including food and beverages. As a result, the U.S. has come to rely on its North American neighbors for a significant portion of its food imports.

In 2022, 60% of U.S. imports from Canada included meat and other animal products in addition to grains and seeds used for products like vegetable oil.

Over the last two decades, Mexico has become an increasingly important partner to the U.S. Now the source of more than $40 billion in imported foods, up from around $5 billion in 2000, Mexico overtook Canada as the U.S.’s biggest food supplier in the Western Hemisphere in 2015 and has since held that lead. We rely on our neighbors to the south for products like vegetables, fruits, snack foods, and beer and wine.

The European Union remains another valuable trading partner from which the U.S. imports a great deal of alcohol and spirits, as well as essential oils used to flavor foods.

The availability of imported food can sometimes be volatile with today’s globalized supply chains—as in the case of avocados and, more recently, the popular sriracha hot sauce. And when the import of even one good dries up, especially a popular product, it can cause price shocks for consumers while supply chains adjust.

Some foods need to be imported because they only grow in certain regions. Other foods may be imported when distributors can get them more cheaply from another country than from the U.S.

Coffee is famously one of the products the U.S. consumes en masse—and one it relies on other countries to produce. Coffee beans grow best in climates surrounding the equator, which includes Central and South American countries. Brazil and Colombia were the top exporters of coffee to the U.S. in 2022, according to the USDA.

But the U.S. is a food-producing powerhouse of its own, even if what it produces looks different than that produced by other countries.

FoodReady

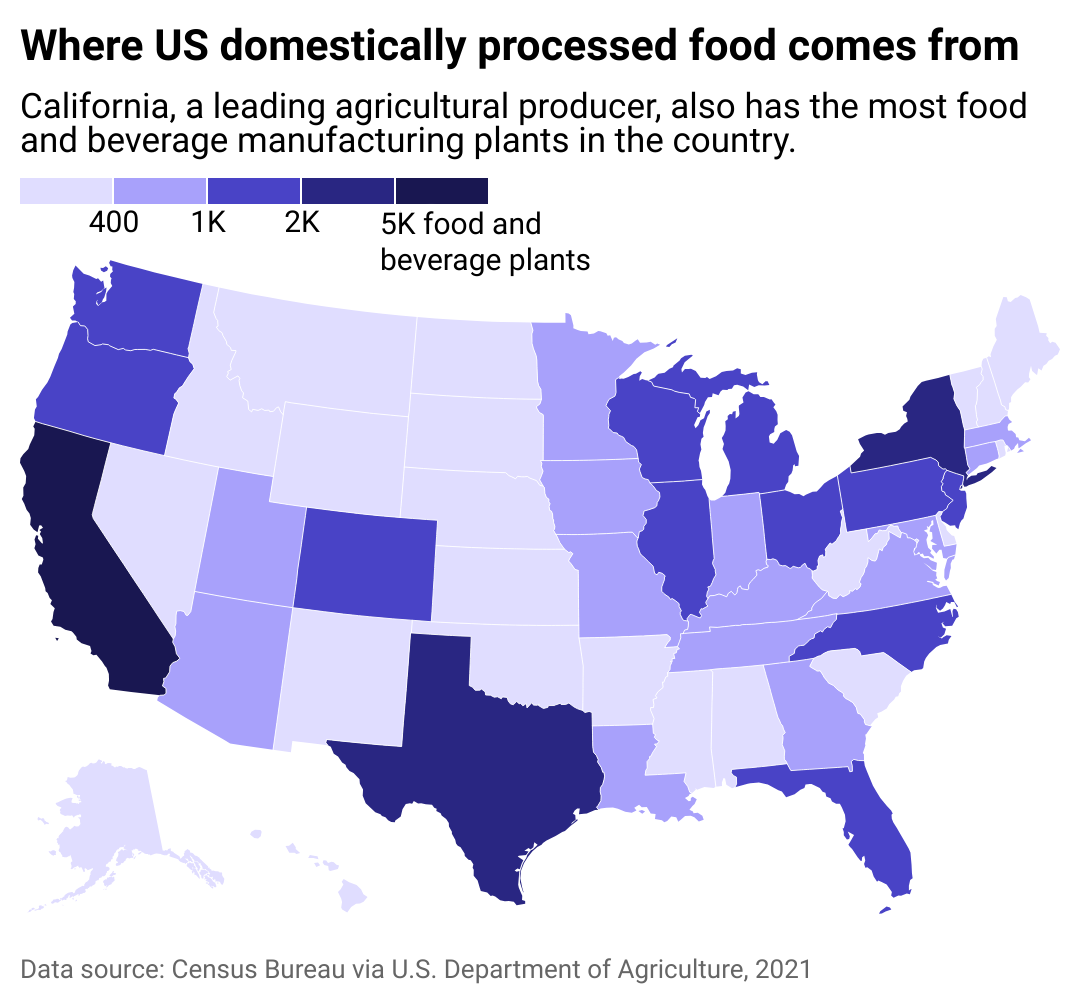

Where domestic food production is concentrated

Although a high share of the products lining the produce aisles of U.S. grocers are imported, that’s not the case for other parts of the grocery store. Sugars, sweeteners, and preserved fruits and vegetables are often imported pantry staples. However, dairy, grains, and meats are more frequently domestically produced.

The U.S. also exported 11 metric tons of processed foods to other countries in 2022, with Canada and Mexico being the biggest buyers. The overall export value that year exceeded $38 billion. Common U.S. exports include processed foods like beer, baked goods, condiments, dog and cat food, and fruits, vegetables, and dairy products.

Domestic processing facilities are most prominent in states like California, Texas, New York, and Florida, which serve as major logistics corridors and seaports, along with Pennsylvania, Illinois, and the Pacific Northwest. Meat and dairy product manufacturing make up the largest share of these types of facilities. When it comes to states’ economic reliance on food processing businesses, Vermont, Alaska, Oregon, Maine, and Montana have the most facilities in proportion to their populations.

Story editing by Brian Budzynski. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on FoodReady and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.