How much does it cost to win Best Picture? Breaking down the biggest and smallest budgets.

Published 3:30 pm Monday, February 26, 2024

How much does it cost to win Best Picture? Breaking down the biggest and smallest budgets.

Sweeping films, epic stories, stacked casts, and ostentatious budgets—these are some of the things that may come to mind when moviegoers imagine Best Picture-winning films. But is that perception always reflected by reality? Not necessarily.

Many factors go into making an Oscar-winning film. In order to win over members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the quality of a film certainly goes a long way, popularity with audiences can help, and a prestigious director or cast certainly doesn’t hurt. Movies of certain genres, like dramas and historical epics in particular, are more consistently favorable towards the tastes and sensibilities of Academy voters than comedies or thrillers.

Sometimes, Best Picture wins have to do with marketing budgets as much as they do with tastes or prestige. In 2023, The New York Times estimated that studios might spend $5 to $25 million to lobby for their movie with Oscar voters. BBC even quoted a figure as high as $500 million for how much the industry is willing to spend on awards campaigning. These lobbying budgets cover expenses like throwing lavish parties to sway awards voters or even hiring “Oscar consultants.”

In the end, awards recognition should all come down to the quality of the movie and whether the filmmaking budget was put to good use. Smaller-budget, independent films like “Nomadland” and “Moonlight” can take home Oscar gold just as readily as a sprawling romance like “Titanic” can.

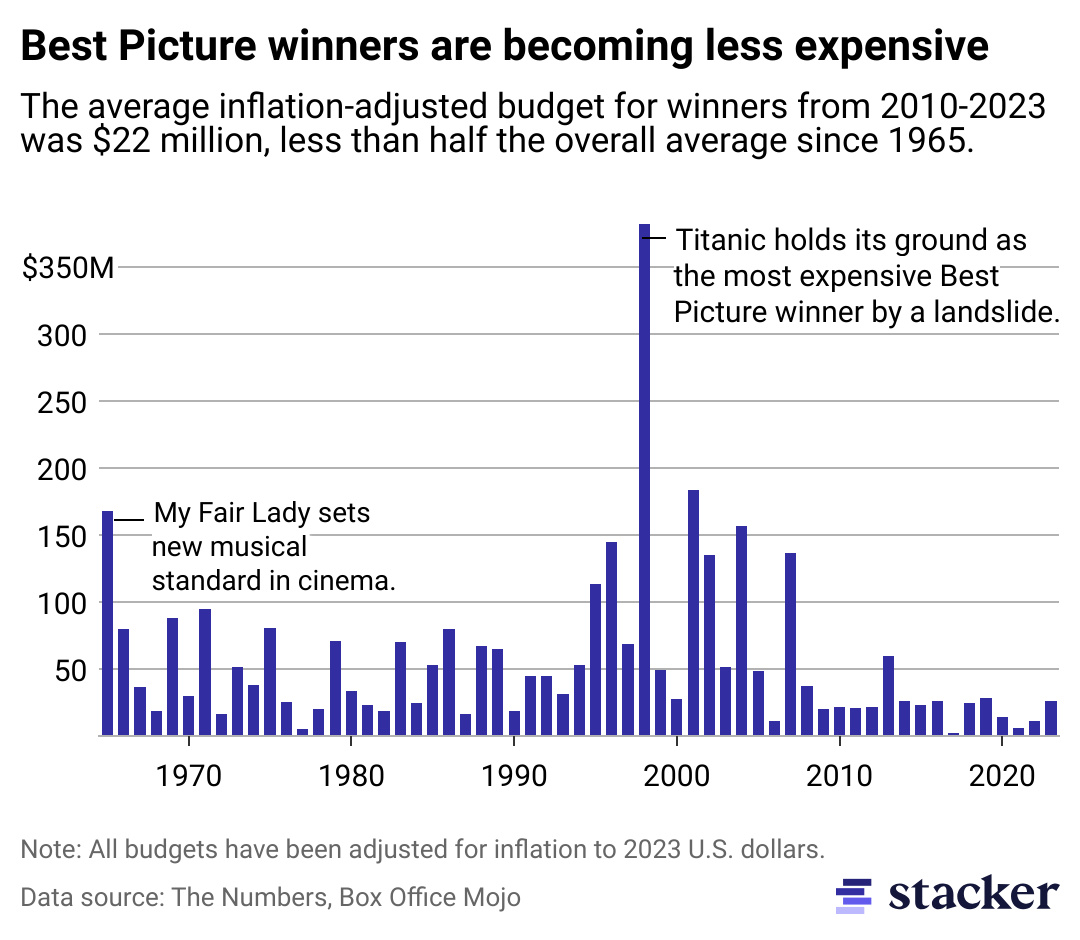

Curious about the correlation between movie budgets and the likelihood of obtaining Oscar glory? Stacker looked at data from The Numbers on the production budgets of Oscar Best Picture winners dating back to 1965—starting with the musical “My Fair Lady”—and drew out insights based on the trends on what it costs to win Best Picture.

Film budgets and grosses have been inflation-adjusted to the year of their release. As movies are more easily seen and widely distributed than ever, the worldwide box office was used instead of the domestic box office to determine the film’s net gain or loss. Keep reading to see what the data reveals.

![]()

Stacker

It doesn’t always take a ‘Titanic’ budget to win the Best Picture Oscar

When “My Fair Lady” was filmed, Warner Bros. spent a hefty $17 million on its budget, or about $168.2 million in today’s dollars. It was the most expensive movie the studio had ever produced at the time, but their gamble paid off. The movie went on to win Best Picture, Best Actor for Rex Harrison, Best Director for George Cukor, plus another five Oscars. When adjusted for inflation, no other movie would even come close to the budget for “My Fair Lady” until James Cameron’s “Titanic” came along more than three decades later.

Prior to “Titanic,” rarely did movies cross the $100-million budget mark, though some came close, such as “Patton,” a biopic depicting the rebellious command of George S. Patton during World War II; “Oliver!,” a musical about a runaway orphan; and “The Godfather Part II,” a crime drama on the life of fictional mobster Vito Corleone in the 1920s.

But a film’s quality isn’t necessarily measured by how sumptuously a production has to spend to get the film made. “Moonlight,” a coming-of-age drama about a young Black man growing up and accepting his identity, had the smallest Best Picture-winner budget ever at only $1.9 million.

How did a film with such a scant price tag snag Best Picture? Aside from a genuinely moving and well-made narrative that played well with Academy voters and feeling particularly “of the moment,” “Moonlight” had the marketing heft of A24 behind it, the boutique independent distributor that clinched its second Best Picture win with “Everything Everywhere All at Once” last year. A24 has become known for its savvy merchandising and very online style of getting its films into public consciousness.

Behind “Moonlight” budget-wise is the Sylvester Stallone classic “Rocky,” which only filmed with $5.4 million. An inspiring sports story about a small-time boxer getting the chance of a lifetime, the film’s low budget partly stemmed from the risky move of casting a then-unknown Stallone in the lead role of the passion project script that he wrote.

Throughout the past decade, Best Picture winners have actually trended downwards when it comes to budgets, with an average of $22.2 million between 2010 and 2023. That’s less than half the overall average since the data became available with “My Fair Lady” back in 1965.

Stacker

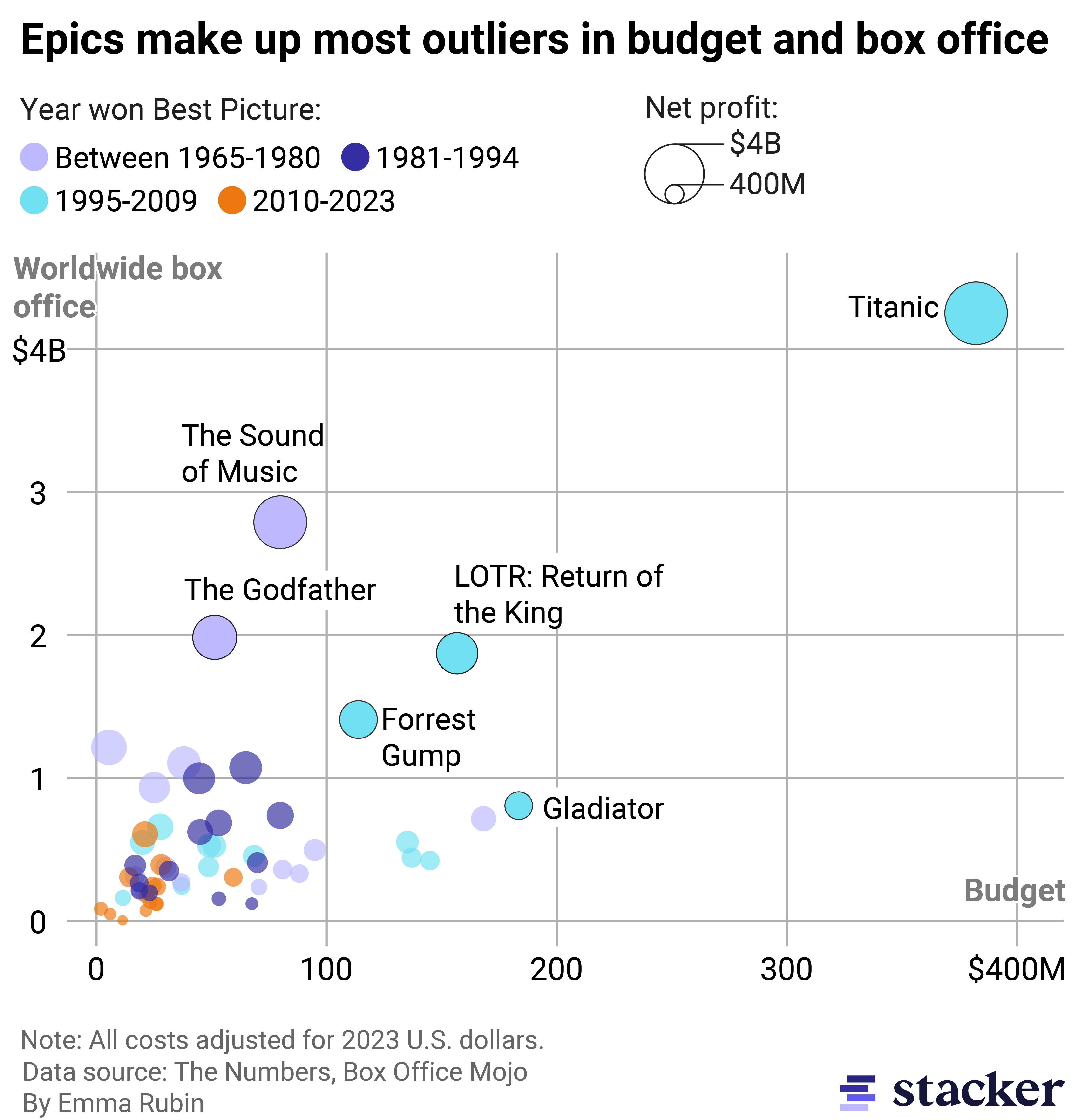

The biggest Best Picture budgets came at the turn of the 21st century

As technology advanced and we closed in on the year 2000, some film production budgets skyrocketed. Aside from “Titanic” taking the top prize back in 1998, a few other films awarded Best Picture between 1995 and 2009—such as “Forrest Gump,” “Gladiator,” and “The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King”—trended above the $100 million range, taking inflation into account. A few of these expensive gambles paid off.

A great example of big bets paying off is “Titanic.” Director James Cameron needed a generous cushion not only for a gigantic cast, massive practical sets, and extensive visual effects but for deep-dive research into the famous sunken ship as well. At an inflation-adjusted price tag of $382.2 million, that investment quite clearly translated to the finished film, which went on to win a total of 11 Oscars out of 14 nominations, including winning Best Picture and Best Director for Cameron. Not only that, but the film is a true blockbuster that made $4.25 billion at the box office.

Another unsurprising big-budget Best Picture winner comes from Peter Jackson’s exploration of Middle-earth. The “Lord of the Rings” trilogy used tons of visual effects, motion capture technology, and on-location, back-to-back shooting in New Zealand. The trilogy’s third installment, “The Return of the King,” won the Best Picture prize at the Oscars in 2004 with a budget of $156.7 million. The film made back its budget in spades with a worldwide gross of $1.87 billion, behind only “Titanic” as the most profitable Best Picture winner during that era between 1995 and 2009.

Another turn-of-the-century blockbuster, “Forrest Gump,” the inspirational story of an unlikely American hero, used a surprising amount of visual effects in order to place the titular character into various famous historical moments, as well as removing Gary Sinise’s legs in order to turn him into Vietnam veteran Lt. Dan Taylor, whose two legs were amputated. The budget for “Forrest Gump” was $113.8 million but it made $1.41 billion at the box office. The movie earned six Oscars (including Best Picture) out of 13 total nominations.

While sometimes a huge budget might seem excessive, in all three noted blockbuster films, a large budget made the look and feel of the films possible. In the end, these envelope-pushing works were hits not only with audiences but also with awards bodies.

Still, if the figures in the data tell any story, it’s that the Oscar game is anyone’s game. Big budgets aren’t the standard, and recently, it appears that less is more when it comes to Best Picture winners. The less films spend, the more potential there is to make a profit.

No Best Picture winner in the past decade spent more than $30 million when adjusted for inflation. With the exception of “CODA,” which actually lost $8.7 million at the box office on a budget of $11.3 million (partially due to distributor Apple’s strategy of having a limited theatrical release for the film the same day it dropped on its streaming platform), every other film in the last 10 years made at least three times its budget back in ticket sales.

For now, it seems the Academy is embracing simplicity as opposed to epic productions filled with expensive effects.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.