1 in 4 Americans are physically inactive. Here's how that impacts you as you age.

Published 4:00 pm Monday, April 8, 2024

1 in 4 Americans are physically inactive. Here’s how that impacts you as you age.

In 2024, nearly half (48%) of American adults made a New Year’s resolution to improve their fitness, according to a Forbes Health/OnePoll survey.

It’s a good goal—because Americans aren’t doing it nearly enough.

Nearly 1 in 4 American adults are not getting the suggested two days of muscle training and 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends. According to a study published in the Journal of Physical Activity and Health, part of the problem could be that only 1 in 10 adults know how much and what kinds of exercise they should be getting to stave off disease and other health ailments.

Guidelines by the CDC recommend “regular physical activity,” encompassing more than just fitness and exercise. It also includes sports and other physical activities that move your body and expend energy. Physical activity can even include active transportation like walking to work or gardening.

Routine physical activity has more advantages for your health and well-being than just preventing weight gain. Regular movement makes your bones stronger and your cognitive abilities sharper, helps you sleep more soundly and feel less anxious, and can reduce the risk of chronic diseases, such as Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and some types of cancer.

Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to analyze CDC data about Americans’ physical activity levels and how they vary by age.

![]()

Northwell Health

Americans are becoming less active

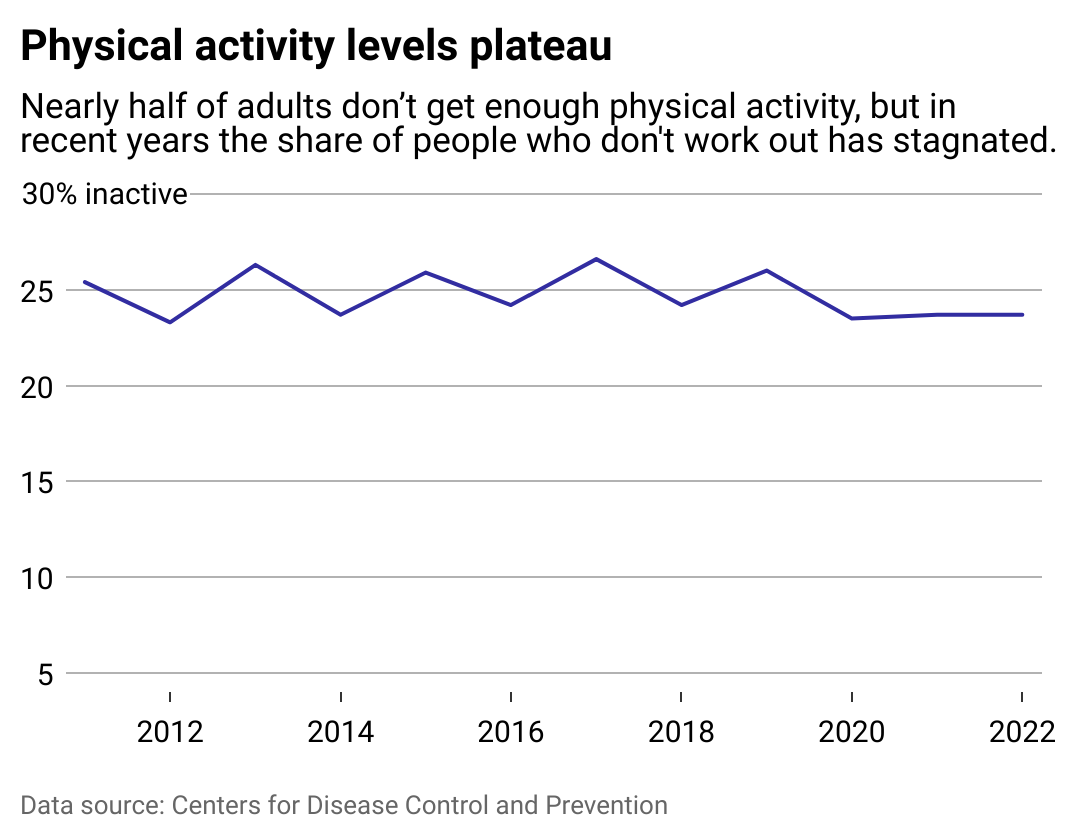

Over the past decade, the prevalence of physical inactivity has remained “unacceptably high,” according to a study in The American Journal of Medicine, despite continued efforts to improve fitness at individual and population levels.

Physical inactivity isn’t just an American issue nor limited to the individual. Government policies can help change the infrastructure, environments, and resources that support a more active population. However, a World Health Organization report published in 2022 found in a study of 194 countries that progress toward policies that aimed to increase physical activity is slow. Over a quarter of created national policies were not funded or implemented.

Variables like socioeconomic status, regionality, ethnic backgrounds, and education correlate with differences in physical inactivity. Technology and how our “built environments” are structured for walkability and safety all play a part in why Americans don’t move as much as they should—in addition to more personalized reasons, like a lack of time, energy, and motivation and fear of injury.

Physical activity doesn’t just prevent chronic conditions; it can help manage them too. Still, like the rest of American adults, people with chronic conditions and disabilities also exercise at lower levels than recommended.

CDC data shows that physical activity levels in adults have dropped and flatlined since 2020 without continued improvement for over a decade. With just an additional 10 minutes of physical activity a day, it is estimated that 110,000 deaths of middle-aged and older adults could be prevented annually, according to research published in JAMA Internal Medicine. Fittingly, CDC data also shows that low physical activity costs the American health care system $117 billion annually.

A 2019 Global Wellness Institute report found that Americans rank #1 for how much consumers spend on physical activity, with $264 billion annually on technology, equipment, and apparel. The same report ranks the United States #20 globally for “sports participation,” measuring people participating in at least one physical activity per month.

So, have Americans always been this inactive? A 2021 Current Biology study comparing 19th-century to 21st-century Americans found that Americans exercise 27 fewer minutes now.

Northwell Health

How age plays a role

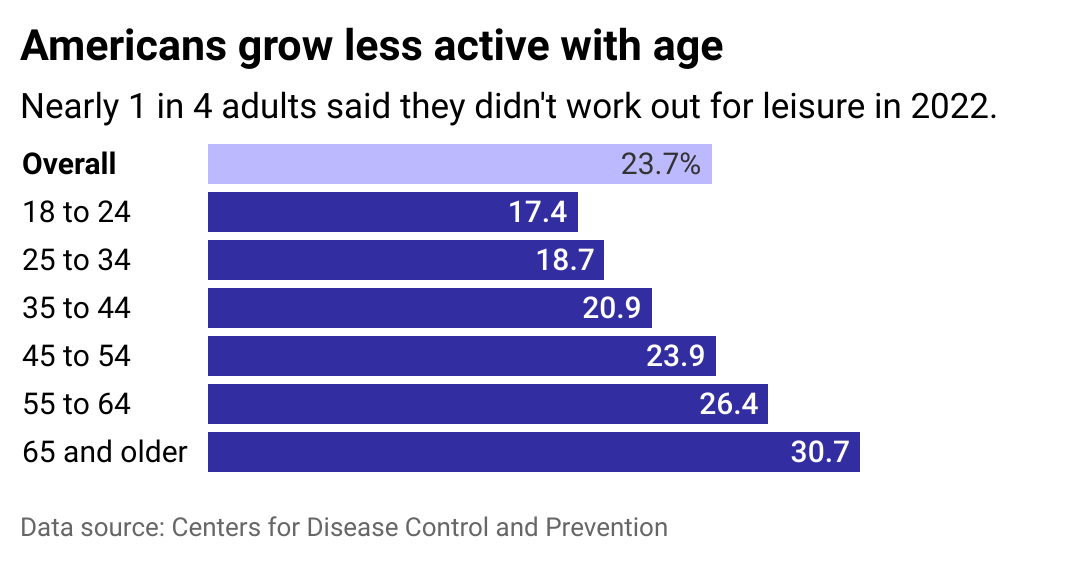

According to the CDC, the pattern of inactivity begins early in Americans’ lives, with 77% of high school students not getting enough aerobic physical activity.

Evidence shows that moving your body earlier in life has a positive yet small effect on healthy aging down the road. For bone density, building strength in our younger years matters. The body keeps bones strong by replacing “old bones” with new tissue—the rate of which can slow with exercise—but production of the new tissue ends around age 30.

“Exercise is the best defense and repair strategy that we have to counter different drivers of aging,” Nathan LeBrasseur, professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the Mayo Clinic, told Time magazine. However, only moderate and vigorous physical activity makes a difference in the health of older people.

In addition to the exercise recommendations for adults, people 65 and older should do activities that improve balance.

According to CDC data, American adults move less as they age. Still, according to CDC data, there’s a more significant drop in physical activity for people aged 65 and older than those aged 55-64. A survey of researchers at the University of Michigan found that COVID-19 restrictions hurt older adults’ physical functioning and health outcomes after falling. Lead researcher Geoffrey Hoffman told the New York Times that the changes in activity levels for this community during the pandemic led to worsened physical functioning, which corresponded with increased falls and fears of falling.

With the median age of the U.S. population higher than ever before, paired with high levels of inactivity, there will be a continued strain on the health system. The CDC’s comprehensive Active People, Healthy Nation initiative aims to motivate 27 million Americans to become more physically active by 2027.

Story editing by Shannon Luders-Manuel. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Ania Antecka.

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

More Stacker National